Adventure Divas (33 page)

The racecourse wanders off into the distance, partly following what looks like a loopy riverbed. The race is twenty minutes long, give or take, and the riders quickly disappear into a cloud of dust and distance. After about ten minutes, news ripples through the crowd that a rider has fallen off and been trampled—which is somewhat serious as we are at least four days (by jeep, much more by camel) from even rudimentary medical-care facilities.

Because of the accident, half of the men drop out of the second race, preferring to save their necks for the last race, which has the biggest kitty. Attention turns to the injured rider, who has been brought back in from the course. He is quite dazed, but luckily he seems to have only broken an arm.

In a matter of hours all the Zen equity built up on the long desert walk drains from my soul. I, a competitive adult-child-of-a-professional-athlete-and-gambler, am planning to get myself into race three. From the moment I heard

race,

my serotonin flooded the zone and drowned out my culturally sensitive alter ego, who heckles:

Whitey! Woman! Culture skater! You just parachute into cultures—bopping around with as much imperialist swagger as the next guy.

My inner voice of condemnation now at bay, I begin to justify a potential cultural trespass. Adventure is a woman’s right, I rationalize. And a willingness to take risk—well, that’s very divalicious. As Keri Hulme exemplifies, we all must pursue our updraft—mental, physical, or otherwise. I humbly, and incorrectly, wrap a

cheche

around my head and walk up to the lead blacksmith.

“Je voudrais monter sur le chameau,”

I say.

Blank stare . . . then slightly bewildered grin.

“Did I get that right?” I ask Vanessa, who is fluent in French.

“What?” Vanessa says. “You

can’t—

You’re joking, right?”

“You don’t understand, Vanessa. Derby Day is a high holiday in my family. I was built for this.”

“Derby Day?” she queries, Europeanly.

“As in

Ken-tuck-eee.

”

I repeat my request to the blacksmith, louder this time, fairly sure he understands French, and willing volume to lead to comprehension.

“Yes, uh, I think it’s the concept that’s the problem, not the language,” says Vanessa.

A frenzied discussion among the blacksmiths ensues. My head swings back and forth, following the debate.

Clearly there is concern.

“Your insides,” the blacksmith finally says to me in French, which I can mostly understand, “may damage the horns on the front of the saddle.”

“My impaled liver is less important than the saddle?” I say to Vanessa.

“Trop chère. Trop chère,”

he says—of the saddle.

It’s true; in this, one of the poorest nations in the world, a saddle is gold, and who am I to make value judgments?

“What are the chances of a liver transplant in Agadez?” I ask Vanessa, half-joking, and continue to lobby the blacksmiths.

“It

would

make great footage,” muses Vanessa, tantalized. “But are you sure you want to do this?” she adds. Vanessa is both producer and director on this shoot. The producer in her realizes it is her job to keep me alive. The director in her feels that

this is the nutgrab.

But I have gone inside my own head, regressed not to my secret happy place, but to that focused, pulsing headspace I used to go to at track meets before the gun went off, in basketball games before the whistle blew, in touch football as the Hail Mary was lobbed.

I barely hear Vanessa saying, “You don’t have to race . . . but . . . but . . . if you’re gonna do it . . . do try to face camera around the last bend.”

The crowd parts and I see before me a ten-foot-tall, fifteen-hundred-pound white camel swathed in multicolored blankets and layers of leather fringe. The camel wears an intricate saddle of silver, leather, and carved wood, which is topped with a lethal trifecta of horns.

“Lots of luck,” Vanessa says, nudging me toward my steed.

I am handed the reins to the beast. “Shhhhh, shhhh, shhh,” I say to him, imitating my fellow jockeys, and he kneels with a cranky, homicidal shriek. I climb aboard my massive camel and line up with ninety or so other contestants, all aggressively jostling for an inside position, yelling at one another and their camels, regalia clanking, crops gripped as tight as the tension in the air.

And this is when it hits me like a tsunami that, this time, I have gone

too far.

I should

not

rip through the Sahara desert on a giant camel competing against veiled men with sharp swords who have done this drill since the time of Muhammad.

Oh, why can’t I be content with life’s calmer glories? It’s not just that I need a new notch in ye olde adventure belt. It is a deep-seated, almost irrational fear that I will miss out on an experience within my grasp that I have passed up because of fear. But here, in the middle of the Sahara, as the sword is about to drop, the

truly

sick thing is: I WANT TO WIN.

Aaaaaand theyyyyyyre offff . . .

The next fifteen minutes are a blur of survival tactics, rapid-fire cussing . . . and wholesale regret. My rusty horseback-riding skills do not translate, and my dream of winning (or at least placing!) is trampled within moments.

I just want to live.

My camel runs fast, a tenth-gear trot, and I am, shamefully, gripping the horns in order not to be flung over the top of the seven-foot-long curvy neck, or skewered like a holiday pig, or both, in rapid succession. I

do

want to live, but my father’s DNA sears through my blood and

mostly

I don’t want to come in last, so I try to do like the jockey just ahead of me who has one leg contortedly wrapped around the camel’s neck to stabilize himself, the other foot quivering the camel’s nape—a sort of Saharan accelerator. I wrap my leg and thump my camel haphazardly with my filthy, blistered bare foot, and he responds like Secretariat at the Belmont, determined to wear the Triple Crown. He lurches us ahead several lengths and passes two contenders. I’m dying to turn my head and look and gauge our lead, but I know that when Lot’s wife fled Sodom and Gomorrah she looked behind her and

—poof—

was turned into a pillar of salt. In Niger this strikes me as a real possibility. I don’t look back.

I’m in the final stretch, eating dust along with two riders behind—one of whom is gaining fast on me—when suddenly the rhythms click and I’m Lawrence of Arabia, no hands, yelling to my camel, the power of a crumbling empire behind me. My bum and the camel’s hump are in perfect sync and we are charging toward the finish, neck and (very long) neck with a taupe-colored camel whose rider is a peripheral blur of indigo. With a final gasp, we place second (to last) by a nose and throttle past the finish line, where we are rushed by a dozen ululating women who surround the camel and smudge indigo on his face.

The women seem particularly thrilled at our performance, which is a bit of a mystery to me since we finished nearly dead last.

“You are the first woman ever to enter a camel race in its history. They can’t believe you actually finished,” the lead blacksmith walks up and says, revealing the significance of my trespass into a five-thousand-year-old tradition. “This girl over here says she wants to race next year,” he adds, pointing to a young woman of about fourteen smiling our way.

“Really?” I smile back, sharing an odd moment of global sisterhood, but also worrying for her. It’s one thing for a privileged traveler to buck mores, and entirely another for a local girl to do so.

Who’s to say: Arrogant traveler inappropriately messes with status quo? Or, a lesson in having to cross the starting line, in order to move it. I jump off the camel, and twist my bad ankle when I hit the ground. I stand, all my weight on one leg, and begin to unsaddle my steed. Villagers are beginning to peel off and return to their homes across the oasis. The girl just watches me.

7.

BEHIND CLOSED CHA-DORS

Dear Inga la Gringa,

I’m going to a Muslim land. Do I really have to wear a veil?

—Perpexed About Persia

Dearest Perplexed,

Your closing, “Perplexed About Persia,” leads me to deduce that the “Muslim land” to which you refer is Iran. This is pretty important, because the religion observed in Iran is not the same as that of Turkey, which in turn is vastly different from Islam as practiced in Afghanistan, or Oman.

So . . . Iran.

You need to wear a veil in Iran.

Iran is a theocracy, that means a religious government. Rule of law in Iran is that it is illegal for women to be in public without a head covering. Veil yer ass up.

With love, Inga la Gringa

Veil politics may have been only in my head in Niger, but

veil,

a four-letter word in the lexicon of some people’s feminism, was sure to be a flashpoint in our next location.

I was sprinting toward this final shoot of our premier season with the scattered, determined energy of a greyhound on its last day of racing: tired but enthusiastic, skeptical yet still loyal, slightly lame, and wondering if retirement meant Sundays in the park or a shot of sodium pentobarbital. (And frankly, not sure which I would prefer.)

Jeannie was in Iran scouting, and I was to go there along with a crew, a few weeks after her return. But after several bureaucratic delays and extra fees, I was getting nowhere with our Iranian journalist credentials. One day our contact who was trying to shepherd the visa process along from Tehran called. The real problem had reared its head. “Today the official intimated that you have too many single women on the crew. American single women are considered a special liability. That’s why the visas are not being granted.”

“Thanks. Uh, right. Okay, let me think. I will call you tomorrow,” I said, and hung up the phone.

“It’s not looking possible to get the whole crew in,” I droned to Jill, sodium pentobarbitally. Jill was our website’s managing editor, and her years as a salty beat reporter always made her my preferred commiserator.

Jill clicked her mouse, pushed our new home page live, then checked the e-mail. “You’d better figure out how to get there, if only to go retrieve your mother. Check it out.”

TO:

I

RAN CREW

FROM:

J

EANNIE

SUBJECT: RE:

F

ASHION QUESTIONS

If you’re asking about clothes, the visa problem must be solved—excellent! I think it’s wise to take one all-black cover-up, that is, scarf and manteau (manteau is a French word for coat—sort of like a loose overcoat) for meetings with officials as a sign of respect. Otherwise, conservative colors (though not nec. black) are OK. Despite having to cover up, am having a GREAT time—Iranians are so hospitable!—Jeannie

Jeannie’s optimism jibed

with our public reality. To outsiders, it appeared we had it made; we’d imagined and achieved an ambitious goal. Episodes of the series had started broadcasting on PBS, and our tiny empire thrived online, with chat rooms, advice, streaming video, and behind-the-scenes info on the series. “Confident, quirky and beautifully filmed,” said the

Chicago Sun-Times.

Hundreds of e-mails were pouring in:

I stumbled on your show and love it! Women have been waiting for it for years! So many shows are male-oriented and we never find out about the people behind the cultures. I’ve struggled with moving away from Chicago for my whole life. After watching the show I’ve decided it’s time to move

onward

! Thank you, thank you, thank you!

Leah

Absolutely the finest armchair tour I’ve ever had the pleasure to see! You deserve enormous credit for dealing with a political minefield without preaching or prevaricating. The women you featured are inspirational!

Greg

But, since we spent our time making TV rather than raising the additional underwriting we desperately needed, the truth was we had a lot less money than anybody knew (a dirty little secret Jeannie and I held close); we were receiving fat, litigious, fire-related envelopes from New Zealand; and now we were having trouble getting visas to our last location.

Too many single women,

pffft.

This was no time to retreat, I thought, pacing the office. I read that in Iran, the political lines are always moving and the rules of the game are constantly shifting, which creates an atmosphere in which social improvisation and sociopolitical agility are survival sports. Time to think Iranian. I returned to my desk, grabbed the phone, and started swapping out the crew, women for men, Americans for Brits—thus, integrity for pragmatism. Seven days later, only twelve hours before our flight departed, a FedEx package arrived containing our visas.

Khoda ra Shokr.

(Thank god.)

The politically charged air

neutralizes Tehran’s infamous pollution, and it feels as if I am sucking pure, sharp oxygen on this, our first day in Iran. The thrill of being here makes the brown baggy smocklike wrap that shrouds the contours of my body and the itchy moss-green synthetic scarf that covers my hair almost bearable. The black Georgia work boots don’t do the look any favors. The crew and I hop into a van to begin our tour of Tehran.

We wanted to come to Iran because it felt critical that our first season cover the Middle East; that we explore divadom in a region where religious, often regressive traditionalism and meddling imperialism from countries like the United States both exist and sometimes collide.

Furthermore, we felt that the Western media was leaving out much of Iran’s complexity. One of the stories not being told in the West, we had heard, was that beneath their veils and behind closed doors, Iranian women were anything but shrinking violets. And that, in fact, women in Iran experience freedoms that are unique in the Middle East.

We’re all crammed in the van, and Vresh, our Armenian-Iranian driver, is expertly navigating Tehran’s main drag. Julie Costanzo is producing; a mild-mannered Brit named Orlando Stuart is the cameraman; Persheng Vaziri and Maryam Kia are Tehran-based producer-translator-fixers; and Parviz Abnar, who handles sound, rounds out our crew. We are on our way to meet Shahla Sherkat, founder and publisher of a magazine called

Zanan,

which means “woman” in Farsi. But first there is a particular building I want to see.

“Here’s the American embassy—well, here

was

the American embassy,” says Persheng, who left Iran for New York as a teenager but now spends half her time in Tehran. “We’re

not

supposed to film here,” she adds, nodding toward a few soldiers wielding Kalashnikovs.

This building marks my first memory of Iran. It was on November 4, 1979, when images of blindfolded hostages started pouring from the Middle East following the return of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, who would go on to lead the country’s conservative, Islamic government. Islamic militants (i.e., politicized students) had seized the American embassy in Tehran and held fifty-two American hostages.

I remember watching those images and thinking how scary it must be to be blindfolded and surrounded by deafening chants. I also remember how careful the Iranian students were in helping the hostages down the front stairs of the embassy so they wouldn’t trip.

We drive slowly by the embassy, later referred to as a “U.S. den of espionage.” The compound is currently a training center for Islamic guards and spreads over an entire city block; a six-foot-tall brick wall forms its perimeter. The wall is freshly painted with sloganry:

WE WILL MAKE AMERICA FACE A SEVERE DEFEAT!

There is an image of the Statue of Liberty with a skull face; there is a handgun painted in the red, white, and blue of an American flag.

DOWN WITH AMERICA.

I find these anti-U.S. images more intimidating than those in Cuba. Perhaps this is because Cuba’s propaganda is from a political era that seems benign, almost kitschy to me, whereas in Iran the symbols, on some level, feel loaded with contemporary meaning.

“Roll film,” I say to Orlando, our cameraman. “Well, uh, on second thought let’s use the small video camera,” I add, grabbing it from the backseat.

“This is the place where the four hundred-forty-four-day seige happened in 1979—” I say to camera with a bit too much emotion for a real journalist, “and we’re not supposed to be filming, so we’re doing so very quickly. We should go faster. Can we speed up?”

The hostage crisis was more than twenty years ago and those images on the embassy steps have

been

Iran to most of us in the West. Like Cuba, little of the reality of Iranian life had been reported in the media since. Even when Iran was bestowed the dubious honor of membership in the tripartite “axis of evil,” the media image still did not widen measurably.

I had heard Iranian friends call Los Angeles “Tehrangeles,” partly because more than a half million Iranian expats live there; but as we continue driving I begin to understand other similarities between L.A. and Tehran. First: traffic. Tehran’s four-lane traffic is crammed with drivers who seem to consider transportation a competitive sport and dents badges of honor. Second: The rich live in the foothills and the less wealthy people fan out across the plain. Third: smog. “The Alborz Mountains are right there, but you can rarely see them,” says Maryam, pointing into a haze. Except for the bundles of fresh, bright flowers for sale that dot most street corners, it’s an aesthetically unpleasant city that seems to be the victim of some poor architectural decisions.

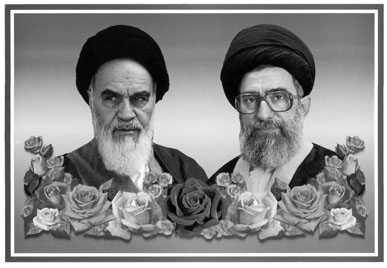

Ayatollah Khomeini Ayatollah Khamenei

We pass the fifth giant sign that displays the same two faces: Ayatollah Khomeini, the now-dead founder of the Islamic revolution, and the current “supreme leader,” Ayatollah Khamenei. Unlike Cuba, there is commercial advertising in Iran (we just sped by the familiar, colorful Microsoft flag), but mostly the prevailing images are guys; big guys, fierce guys, bearded guys, and most of all

dead

guys—martyrs. The two supreme leaders dominate, but their images vie for space with these lesser-known martyrs, hundreds of thousands of young men who died in the war with Iraq that began in 1980 and ended in a virtual stalemate in 1988.

Glorification of martyrs has become a political tool to assuage and convince a population that losing their sons was worthwhile. Even now, parents of each of these men receive a stipend from the government, which is extremely significant in a country with a 20 percent unemployment rate. This payout buys support for the “mullahs,” which is how most people refer to the minority conservatives who rule. Even more colloquially, the mullahs are referred to as “they” or “them.” (As the shoot would progress I would come to understand the fear inspired by, and omniscient qualities attributed to, these ubiquitous pronouns.)

“The mullahs can run a religious revolution but not an economy,” sighs Maryam good-heartedly between translating signs for us:

THE BEGINNING, THE END, THE APPEARANCE, THE DEPTH OF EXISTENCE IS GOD—THE QUR’AN; IT IS OUR DUTY TO THANK THE MARTYRS—SUPREME LEADER;

and,

AMERICA CANNOT DO A DAMN THING.

I notice that Maryam must have brown shoulder-length hair, as a bit has fallen from beneath her royal-blue cotton scarf. We haven’t spent time together outside of work, and so have not yet seen each other unveiled. Maryam, an Iranian who spent much of her youth in London, quickly tires of translating and rolls her eyes at me, as if to say,

We look right through this propaganda, why can’t you?

Persheng, tall, thin, and dressed in something that looks like an oversized raincoat, is also worried that we’re a little too focused on the Islamic signage. She pulls me aside when we stop to get a close-up of a sign with a silhouette of a fully covered woman. The sign encourages good

hejab

(the Islamic dress code). In Iran, women are required to wear a head covering—a veil—starting at age nine, but not the full chador (a head-to-toe, tentlike garment;

chador

actually translates to “tent” in Farsi).