Adventure Divas (6 page)

when my grandmother came she brought a bit of spanish soil

when my mother left, she took a bit of cuban soil

i will carry no bit of homeland

i want it all above my grave.

So it is love of homeland, rather than love of the loins, that she chooses to share with us. But I’m beginning to think, in this place of wide-ranging eros, they’re not so far apart.

That night I’m lying

on a bed blotting my forehead with a wet hand towel. The weather delays that left us waiting in Cancún ended up shaving three days off our shoot, resulting in frustratingly brief visits with the divas. “It’s like McDiva Nuggets! The storm just killed us,” I say to Jeannie privately in our Matanzas hotel room. My complaint elicits an apology; and thus, I have prodded Jeannie into violating one of the ten commandments of second-wave feminism: Thou shalt not apologize for the weather.

The exigencies of making television (tight budgets, head-spinning schedules, neurotic behavior, and finicky equipment) seem at direct odds with creating heady, well-simmered storytelling. What I’d initially hoped would be in-depth biographies are more likely to end up being snapshots of women whose lives allegorically represent their country. I silently vow that future shoots will be at least three weeks long, rather than nine days.

“Maybe this is why television is so often banal—no time for depth?” I ask Jeannie.

“It’s all about getting the nutgrab,” she says while logging film cans.

“The nutgrab?” I ask, assuming it’s a term left over from her days reporting from the locker room.

“Yeah, the important core of the story, succinctly put.”

“Nutgrab,” I repeat, liking it. Strange. But Mom must know what she’s talking about.

The phrase, which I would immediately latch onto for the duration, reminds me of my grandmother. Some years ago when I told my grandmother about a struggle to hammer a meandering college essay into shape, she responded with a parable.

“Hol, did you ever hear the one about the fifth-grade teacher who was tired and wanted some quiet time so she assigned her students to write a story she thought was impossible?”

“No,” I said, wondering what this had to do with the significance of windows in Willa Cather’s

My Ántonia.

“She sent them all back to their desks with the admonishment that all good stories must have Religion, Royalty, Sex, and Mystery. She figured she’d have a good two hours to read her Harlequin,” said my grandmother. “Well, little Suzy walked up to her desk one minute later, said she was finished, and handed her the paper.

“ ‘That’s impossible,’ ” said the teacher, who looked down and read the story:

“ ‘My god, said the Princess, I’m pregnant, whodunit?’ ”

Somehow, remembering my dead grandmother’s joke gives me hope about our show, and perhaps even about television. The “biggest ideas” can be delivered in the smallest packages. Poetry is one case in point. Maybe TV is another. My new-medium learning curve continues. I look over at my hardworking colleague. Jeannie. My mother. It occurs to me how much easier it has always been for me to take lessons from my grandmother, rather than from her. Taking a cue from Santería, I wonder if ancestor worship can start before the ancestor’s death.

Jeannie and I sit together, compiling our notes, making plans, and her thighs don’t even cross my mind.

Leaving Matanzas,

heading into the countryside, we discover that people needing rides stand about on corners to flag down vehicles. Or, for a peso or two, they pack into the beds of old Russian trucks belching black smoke. Our white van pulls out into the fray, pointing toward Santiago de Cuba. For the next several hours we join a light, varied trickle of tractors, scooters, pedestrians, and buses that make their way through the quiet Cuban countryside. Scrubby grass fields give way to endless lush cane farms, which give way to the occasional small town, always friendly seeming in their washed-out pastels and the Caribbean light. Then finally we close in on the place where we’ll stay for the night, Lake Zaza. From what I’ve read, Zaza will provide a bit of respite. I want to shore up morale in the group and rejuvenate my creative brain cells for the final few days of the shoot. And—

“Take a right here,” I say, directing us off the main highway. Jeannie looks at me suspiciously; I’m usually wholly uninvested in where we stay.

I pump my arm in a casting motion. She nods knowingly.

We pull up in front of a duck-hunting lodge that abuts the lake, and proves charming, in a Stephen King–ish kind of way. Grand. Empty. Currently not a hot destination point. But the prospect of fishing isn’t quite the same without my own rod, which I had mistakenly left at home.

“It’s like if you didn’t have your trusty Zeiss wide angle,” I say to Cheryl, trying to make her understand.

“Whatever,” the Manhattanite responds, her eyes wandering off toward the deserted lobby, which has an empty, thatched-roof open-air bar attached to it.

As a child, I chased trout in the soggy Northwest with my grandmother, who, in a single gesture, could teach me how to thread worms on hooks

and

view the world with political precision. Balancing

The New York Times

on her knees, she would soak up the latest minutiae of the Watergate scandal while awaiting her prey.

“Take that, Tricky Dick!” she’d suddenly bellow, rocking boats a mile away as she reeled in her hapless catch.

Cuba is surrounded by water, but I’d noticed that, strangely, fish was never on the menu in restaurants there. Another paradox. Encyclopedia Pam filled in the gaps over dinner at the duck lodge.

“When the Soviets crumbled and famine became a real threat here, Fidel tried to offset the cultural bias against fish eating by handing out fish recipes on slips of paper wherever he went. Didn’t work,” she said, forking the last bit of chicken on her plate.

If Cubans don’t eat much fish, and don’t fish for sport, then Cuba’s fish have been growing fat for the past three decades! This is an interesting and providential side effect of Cuba’s political isolation.

I read aloud a quote from a copy of the

Cuba Handbook:

“ ‘Cuba is a sleeper with freshwater lakes and lagoons that almost

boil

with tarpon, bonefish, snook and bass.’ ”

Cheryl doesn’t get it. “What exactly is the attraction? The five

A.M.

call time? The icy waters? The slime?”

I try to explain rhythm and meter, and angling’s strangely satisfying intellectual depths. Boldly, I wax poetic about the scrumptious pandemonium of the take, the sloughing away of worldly troubles, the high of tangoing with a primeval creature from another world.

“I respect your passion, but I don’t get it,” she says with a touch of pity. “And what,” she adds, “is a snook?”

After dinner I lobby Cheryl hard. She is behind the bar learning how to make mojitos from the bartender, José. (“The art is in the muddling,” he tells her.) Every other crew member has flatly refused to go fishing with me, opting instead for our first, and as it would turn out, only, chance at a seven-hour night of sleep.

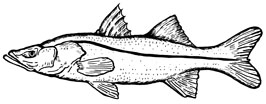

Snook

“Listen to this,” I say, again quoting from the

Cuba Handbook.

“ ‘Americans fishing home waters apparently catch, on average, only one bass every two days of fishing. During those same two days a bass fisherman at Lake Zaza might expect to catch a hundred bass of incredible quality.

There’s a good chance that a world-record bass exists in Cuba

’ ” (emphasis mine).

“Okay,” she agrees, tossing a final sprig of mint into the tall, thin glass. “I’ll go fishing with you, but I’m just going to watch, and maybe film.”

At four-thirty

the following morning I knock on her door. I have few reservations about stealing these few hours from the shoot, while the others rest up. Fishing is never the wrong thing to do. On a tip from last night’s bartender, we go in search of a man named Cheo.

Cheo is old and weatherworn, and his gait transmits a blend of resignation and dignity. The romantic in me calls up the image of Hemingway’s Santiago in

The Old Man and the Sea,

even though it turns out Cheo has a boat with a motor (not a skiff with a sail), works with a rod (not a long line), and, most notably, is fishing for a living (not living for a fish). But, like Santiago, Cheo speaks not a word of English.

As dawn breaks we motor out for the morning bite. Apricot skies. Calm waters. Mimed promises of

bigguns.

I steel myself for the massive lure that will replace my usual tiny nymph, and signal a fall from grace. Cheo pulls a six-inch-long, obscenely pink, and very barbed rubber worm out of the pocket of his windbreaker and dangles it in front of our faces. Cheryl blanches.

The effete fly fisher in me is horrified—but my inner angler, bred on midwestern bass and candy-striped Mepps, screams out in carnal joy:

These fish must be enormous!

I start casting.

Cheryl finesses her cameras like a musician before the big performance, then stops, as if she’s received a signal from some cosmic maestro.

The sun breaches the horizon and the water gently laps against the boat. Time is metered by the reel’s muted clicks. We do not comment, or joke. For at least twelve minutes not a note of irony passes between us. It is one thing to know you can work together, another to know you can be silent together, and, perhaps most profoundly, to know you can fish together.

Strangely, I feel as if the entire shoot—the nerve-wracking entry into the country, the inspiring but frustratingly brief interviews, the ubiquitous cakes, and the crew camaraderie—have led up to this moment. Cheryl, and this timeworn ritual, remind me that work and play

can

be one and the same, and the global pilgrimage regains focus.

But sincerity hits the floorboards as my forearm plunges toward the bottom of the boat, and the moment collapses in on itself. A tank of a fish, but a fighter nonetheless, the

pez

I’ve hooked has me waltzing around the tiny boat, Cheo following my lead, net in hand. As the battle rages, Cheo manages to light a cigar, and a boatful of loud Italians motors over to our honey hole. Cheryl bobs and weaves, filming and giggling. “Yee haw,” she yells from behind her Beaulieu. Cheo puffs calmly, but my endorphins surge with each and every centimeter of line the fish takes.

Chica

against fish. A beating sun. The mighty swordfish (well, I mean bass). A duel of passion, nobility, and, increasingly, ego. And then, to put it in spare Hemingwayesque prose—

I win.

My forearm bows as I haul in the glistening large-mouthed bass and I am breathless at the size. The fish tops twelve pounds, dwarfing the measly bass of my youth.

“¡Buena pescadora!”

Cheo yells out from one corner of the boat; and Cheryl just keeps repeating with city-girl awe, “Oh my god. Oh my god. Oh my god.”

On the way back to the lodge, just as the last traces of morning light’s magic veil burn off, Cheryl says, “It’s not about the fish . . . is it?”

I smile and respond, “Whatever.”

The piercing blue sky

is crystal clear the next day when we make a pit stop in Camagüey. A young, green-clad Cuban militiaman gives a friendly nod and shifts his big Kalashnikov to the other hip. I’ve seen less “military presence” in Cuba than I expected. Years of ingesting media images of revolutionaries in fatigues must have colored my expectations. On my first day here, this guy with a gun may have raised my fear hackles. But the warmth and openness we’ve experienced from Cubans makes it difficult to be intimidated. I nod back to the soldier and climb past him to the top of the pyramid-shaped Che Guevara memorial. A giant bronze statue of Che (also with oversized weaponry) stands on top of the structure. I have been reading Che’s

Motorcycle Diaries

and may have to rethink my earlier theory that he would have become a fly fisher. The privileged cult would have surely chafed at his Marxist tendencies. After all, fly fishers spend hours watching bugs, tying flies, wandering in the poetic bliss of nature, all in an effort to catch a fish and then

let it go.

In short, we have

time

and we

don’t need to eat it.

A perfectly acceptable definition of privilege.

Born into a (slightly on the wane) bourgeois family, Dr. Ernesto “Che” Guevara hopped on the back of a motorcycle in 1953 and became an original “doctors without borders” type, with Karl Marx in his hip pocket. While he would go on to lead an important social revolution, those youthful South American road trips seemed as much loaded with machismo as with budding revolutionary altruism.

Catherine knows a more contemporary revolutionary whom I find at least as compelling: Assata Shakur. Since deciding on Cuba as our first location, we have been trying to connect with Shakur, a former Black Panther who has been a fugitive in exile in Cuba since the late 1980s. Catherine had said over the phone that meeting Assata was a very delicate matter, and later, on the ground in Cuba, no doubt tired of my pestering, she had asked me to stop agitating. “I’ve passed several messages but haven’t heard back. You need to know that when dealing with Cuba it’s best to never expect and never push. And then it will happen.”