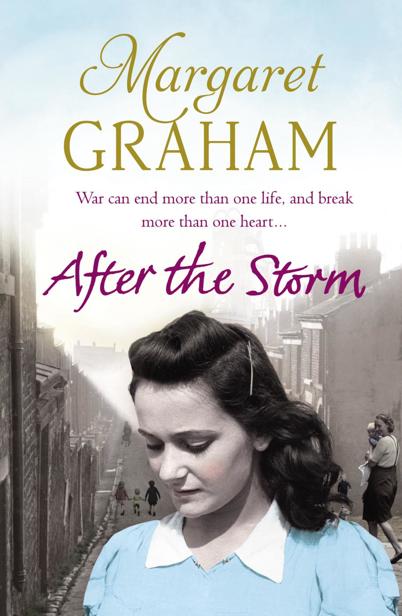

After the Storm

Authors: Margaret Graham

Tags: #Chick-Lit, #Family Saga, #Fiction, #Historical, #Love Stories, #Loyalty, #Romance, #Sagas, #War, #World War II

Contents

‘I am in despair too, but I want to go on living, fighting, getting out of here to something better.’

Born into hardship in a Northumbrian mining village, Annie Manon needs all her strength to survive the bleak years following the First World War.

As her family fractures around her, she longs to make something of her life.

Through hard work and determination Annie eventually leaves the poverty and despair of her childhood behind her. But then war breaks out once more, taking her further away from her dreams and those she loves most.

And it is all Annie can do to keep hope alive . . .

Margaret Graham has been writing for thirty years. Her first novel was published in 1986 and since then she has written a further twelve novels, and is now working on her fourteenth. As a bestselling author her novels have been published in the UK, Europe and the USA.

After the Storm

was previously published as

Only the Wind is Free

, and is based in part on her mother’s life.

Margaret has written two plays, co-researched a television documentary – which grew out of

Canopy of Silence

– and has written numerous short stories and features. She is a writing tutor and speaker and has written regularly for Writers’ Forum. She founded and administered the Yeovil Literary Prize to raise funds for the creative arts of the Yeovil area and it continues to thrive under the stewardship of one of her ex-students. Margaret is now living near High Wycombe and has launched Words for the Wounded which raises funds for the rehabilitation of wounded troops by donations and writing prizes.

She has ‘him indoors’, four children and three grandchildren who think OAP stands for Old Ancient Person. They have yet to understand the politics of pocket money. Margaret is a member of the Rock Choir, the WI and a Chair of her local U3A. She does Pilates and Tai Chi and travels as often as she can.

For more information about Margaret Graham visit her website at:

www.margaret-graham.com

To my family

Little Annie Manon was come home. Standing on the wind-whipped dune, lifting her face towards the lightening sky, she welcomed the North-East bite. She thought of the Wassingham she had known, the black streets of her childhood that seemed a million years away now.

The sand stretched clear and clean, all blemishes swept away by the tide before they had a chance to settle. God, she thought, who’d believe the pitch-black was creeping down to this beach last time I was here. She shook her head. Where did they dump the coal dust now she wondered – or had the miners been tidied away also, rationalised as though they’d never been?

But they had been there all right and somewhere the workings would be standing; stark and silent perhaps, but you could not wipe away completely years such as those or the memories that lingered.

She shivered, remembering the sound of the disaster whistle cutting through the loudest noise, bringing fear into every kitchen in the pit villages. Bet would slowly and quietly lift the latch and stand, helplessly watching the hurrying women, shawls hastily wrapped round greying faces and bowed shoulders, their breath white and thin as they struggled to go faster still. Please God, please God, not one of mine this time but none of this showing on their rigid faces and Bet hugging to her the certainty that it was not her pain this time because she had faced that long ago.

Annie could still feel the rough-textured dress of her stepmother as she clutched it, pulling it to one side so that she could also see, but not hear, for never a word was spoken on the long private walk to the pit-head. She was to nurse those miners in later years and she could never be professionally detached in

the face of their grimy courage and determined humour.

Annie had been called a bonny lass then with her dark hair and eyes; though the eyes were not so dark really but hazel, deeply set under arched brows that cast a shadow. Like her ma, she was hinny, she had been told. Annie frowned with the effort of remembrance. The gnarled hands of Bet had always repulsed her. How coarse and vulgar she had seemed against the slight refined frame of her father. Annie sighed. How cruel children are, she thought, condemning so easily with no mercy given, even though they knew it was being asked.

Poor Bet, no wonder her hands were distorted; whose wouldn’t be, hulking great kegs up to the shop from the cellar, corking and uncorking barrels for a trade that increasingly failed to give them a living. She remembered the smell of beer, the darkness of the small one-roomed store which sold cigarettes as well as Newcastle Brown. It was set in a street which was indistinguishable from the other back-to-back terraces which made up most of Wassingham. A village which had grown into a town after a station had been built and yet more pits had been opened. The pit wheels were always there against the skyline and the slag heaps too, though hardly noticeable because they were so familiar. And there was the smell of the coal which overlaid everything.

Their father’s shop was a sorry remnant of the chain of wine merchants, the ownership of which should have been handed down from her grandfather to her da and his brother, Albert. Instead her father and uncle had been forced to sell it all piecemeal to settle the debts of a business which had been destroyed by the war. Her father had then leased one back from Joe Garter for the privilege of having something to call a job.

Those First World War years had ended more than one life she knew, broken more than one heart, but perhaps you only really cared deeply about your own particular grief. The rest were merged into a greyness against which the matt blackness of the pain stood out sharply and unavoidably.

She settled herself down, spreading her Harrods mackintosh on the sand. She did not want to return yet to Tom. She wanted to remember how it had been before she left; never to return until today. Her own hands were work-worn now, the wedding ring slipped easily up and down between the swollen joints on her right hand. Ruby Red of the left would never dance for

anyone again. She smiled and stroked its crookedness, shaking aside the pain.

Leaning her head back, she let the wind sweep the fine hair where it chose. Her profile was strong and saved from prettiness by a chiselled nose. The lines of ill-health ran deep to the corners of her mouth and the sallowness of her skin owed as much to that as to the heat of her war years. Laughter had carved its path also. Maybe, she mulled, it was the laughter that carried her through, but only so far for it had then cracked and dried, its husk blown beyond her reach.

She nestled deep into the mohair sweater which was too large for her slight frame but that was how she liked it; her cuffs were undone as well. The restraint of tightly buttoned clothes was unbearable to her. Strange that, she thought, remembering the long summers when they strolled in the spent warmth of the evenings, smoking and eating vinegar-soaked chips. Strange to hate such restraint when I so longed for it as a growing girl. Eeh, Annie, no one’ll mind if you’s late, we’ll get others back first or they’ll be for it else.

Tears threatened even now, so many years later, glinting like the coins they had bashed and filed from scraps of lead pipe before the fair. She laughed deeply in her throat. That was class she thought, remembering Don and Georgie choosing the stalls round which to loiter; the ones with the overworked taddy on whom they would then all surge, Tom, Grace and Annie at the front because they were smaller.

She picked up a handful of sand and let it fall through slightly parted fingers. The wind blew it back against her body. It was a good gang, she reflected, but one which yet another war has done its best to scatter. Annie sighed as she traced her salt-dried lips with her forefinger. In the beginning though, there were just the two of us, Don. And you are the one who stayed, deep down in your guts, stayed where you were and what would our da have thought of that, she pondered wryly. She could never forget her father’s chronic need for his children to climb back up as he had failed to do.

Annie allowed herself then to remember the first time she had consciously seen her father but by then he was already wounded beyond endurance, with his youth long away and joy a distant memory. It was 1920 and she was 7. Don was 9.

The air had been sharp on her chapped face, much as it was now, and it had stung the roughened lips still wet from licking. The salivary warmth had eased the misery for a moment but as the wind whipped it dry again it hurt even more. She hunched herself deeper into her coat and wished Don would hurry. There was no way of ducking out of the cold here by the school gate. The railings were as dull as the iciness all around and their chill sank into her back as she changed from foot to foot, dragging her socks up with the toes of her boot. She grimaced at the thought of Aunt Sophie having to make yet another pair of garters. I don’t know where you find holes to hide them in Annie, she’d say, I really don’t. And you standing there the image of your bonny mother so’s I don’t have the heart to scold you.

Annie was glad it was Friday because Don would be here again, home from Albert’s for hot scones and buttered toast. She wished he hadn’t gone to live with their uncle. It was strange how things and people always seemed to disappear eventually and she rubbed her nose on her sleeve.

First it had been the light and pretty house on the hill that had gone. One day when she was 3, the light had simply fled and shadows had filled the rooms as the drapes were drawn across the windows; they were pink like plums. Everyone had spoken in whispers. Jane, the nanny, had red eyes and there had been a quiet emptiness until she and Don had moved in with Aunt Sophie but before that her father had come and gone from the big house, dressed in khaki with a black band on his arm. She knew now that he had come to bury her mother and that after her mother died, the house had too. Did the house always die she wondered, and shivered as the wind suddenly blustered down the street.

The cables were grinding up the slag-heap which had been created behind the school. She could hear the clang as the buckets emptied their waste when they reached the tipping gear.

She and Don had clambered into a black taxi when they travelled from the big house for the last time and Sophie’s arms had hugged them to her. Her coat had been black and smelt of damp and they had passed the station and a church with no steeple, down street after street until they were at Sophie and Eric’s, backing on to the railway line.

It was when she was 6 and Don was 8 that Albert had come for Don. She had thought her brother would stamp and scream and not leave as she would have done, had she been taken from Sophie and Eric’s and put in that smelly old shop a good mile across town. But Albert had said he would give Don sixpence each week for running errands and he had laughed and gone.

The wind blew again bringing the noise of the cables nearer it seemed and then died away and the mist crawled in up the street. Again she searched the road for Don and she wanted someone but did not know who.

In the failing light she first heard, then saw her brother. Eeh, it was grand to see the lad but he was walking with someone, holding his hand and at this she frowned. Aunt Sophie had told her that, even though she was old enough to start school, she was never to talk to strangers and here was Don, for goodness sake, holding this big, strange hand. She faltered as they came close, unsure of what to do.