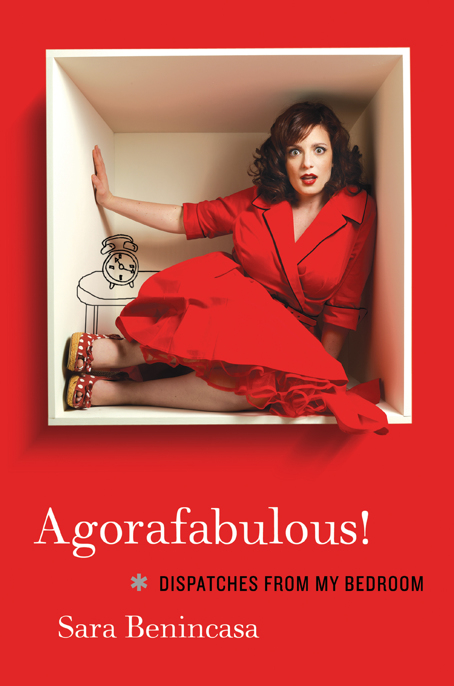

Agorafabulous!

Authors: Sara Benincasa

Agorafabulous!

DISPATCHES FROM MY BEDROOM

Sara Benincasa

So keep fightin’ for freedom and justice, beloveds, but don’t you forget to have fun doin’ it. . . . And when you get through kickin’ ass and celebratin’ the sheer joy of a good fight, be sure to tell those who come after how much fun it was.

— Molly Ivins,

Mother Jones

Contents

I didn’t know what to call this part of the book. I guess you could call it a preface, but that sounds too fancy to me. I’ve already got an introduction (that comes later) and this obviously isn’t a table of contents. You might call it a foreword, but don’t

other

people usually write forewords? You know, like the author’s famous friends. I’ve got some of those, but they’re usually pretty busy signing autographs and swimming in great vats of their own money, Scrooge McDuck–style.

Anyway, I want to tell you some important stuff up front, before we get to the rest of this tragicomic journey into the depths of my lady-soul. This story is mostly true. I tried my best to keep it real, as the children say, but I’m not a fucking journalist. I didn’t have a damn tape recorder on me during every conversation.

Please also keep in mind that when a lot of the stuff chronicled in this book actually happened, I was crazy as a loon. On meth. In a crack house. I had to fill in some of the fuzzier memories with my best guesses as to what actually happened.

A few of the characters represent amalgamated mishmashes of people I once knew. I changed some names, places, and identifying details for a couple of reasons. I still talk to some of the people in this book, and I’d like to keep it that way. I don’t talk to some of the others, and I’d

really

like to keep it that way.

Rest assured that the grossest, meanest, ugliest, most foolish things that

I

do in this story all actually happened in real life. I subscribe to the notion that if you can laugh at the shittiest moments in your life, you can transcend them. And if other people can laugh at your awful shit as well, then I guess you can officially call yourself a comedian.

That is all. Thank you. I hope you like the rest of my book. If not, feel free to use it for kindling to warm yourself in the cold night when the Revolution comes. And oh, it’s coming.

When I was seventeen years old, I met the hottest guy in seriously the entire

world

at a free academic summer program run by the state of New Jersey. The camp, held at a public university down the Jersey Shore, was called the New Jersey Governor’s School on Public Issues and the Future of the State. It doesn’t sound like the place to find Adonis, but there he was: a dreamboat straight-A football captain named Kevin, whose extracurricular activities also included coaching little kids’ sports teams and volunteering at a convalescent home for nuns. When he turned seventeen that summer (he was young for his grade), his mom brought a cake with a car on it, because he and his twin sister were finally going to get their driver’s licenses. He told me once that his sister was the only person he really trusted. She and I had the same first name, except hers had an “h” at the end and mine didn’t.

He was very nice, too nice to be true, and the other students at Governor’s School—Type-A student-council brats, mostly—wondered what his deal was. You couldn’t be

that

smart and

that

hot and

that

nice and not secretly be crazy, or a werewolf, or something. I found it deeply disappointing that he failed to offer to relieve me of my virginity. And at a certain point, his plastic perfection started to weird me out. Oh, I totally still would’ve let him put his fingers down my pants, but a strange kind of resentment arose within me, as well. As a funny (read: insufficiently hot) girl, I wasn’t privy to the mating behaviors of popular alpha males. But I was savvy enough to intuit that I was never going to be Kevin’s girlfriend.

Eventually, I did find a boyfriend. He wasn’t as hot as Kevin, and we never had sex, but he played tennis and was good at finger-banging. Plus, we liked a lot of the same books, Philip Roth’s

Goodbye, Columbus

chief among them.

Governor’s School ended, and we all went off to our respective high schools to start our senior years. Kevin entered a new high school in a new town and was immediately nominated for Best Looking, Most Likely to Succeed, and Best Personality—a stunning trifecta of high school laurels. I heard about it and thought, with slight annoyance,

Of course.

Then, one night in the spring, he walked into his garage, filled a bottle with gasoline, brought it upstairs into the bathroom, locked the door, poured some of the gasoline down his throat, soaked himself in the rest, and lit a match.

When they broke the door down, he was still alive. He still responded to his name. The end took a little more time in coming—less than a handful of hours, but if you measure time in pain, I imagine it felt like years to him—because indeed he was still there, after the fire, still conscious, still feeling everything. I think he wanted it that way. Not for him the quiet chemical sleep of too many pills; not for him the instant, violent relief of the shot to the head. If his death taught me anything, it’s that when life doesn’t hand us the punishment we think we deserve, we are wholly adept at delivering it unto ourselves.

In the weeks that followed, I heard rumors about things he had supposedly done and things that had supposedly been done to him, but they were rumors only, confused teenagers’ attempts at explaining the inexplicable. I have always regretted not going to his funeral. We were never very close, but maybe it would have made more sense, being there, seeing his family and all his friends. Maybe

he

would have made more sense.

I’ve thought of him often in the intervening years, through friendships and love affairs, college and graduate school, times of joy and times of breakdown. I don’t know if I believe in God. I don’t know if I believe in Heaven. I don’t know if I believe that Kevin is watching me, or that he hears me when I speak his name. He didn’t watch me often on earth, so I don’t know why he would feel the need to do so from any other plane of existence. Maybe I should’ve worn tighter shorts the summer I knew him.

What I do know is that Kevin was very much on my mind during the times when I walked myself to the edge of the abyss and stared down, feeling my toes curl over the lip, seriously considering giving myself over to the yawning absence of anything. And so Kevin has been with me, in one form or another, perhaps just as a thought, on numerous occasions.

He was with me when I stacked empty cans and jars against the wall of my tiny apartment because I was afraid to take the recycling outside—or do anything outside the confines of my home. He was there when I began urinating in cereal bowls and shoving them under my bed because I was frightened of using the toilet or even the sink. He was there when I admitted, finally, that sometimes I thought about doing secret and terrible things to myself—and I didn’t put those things into words, because I didn’t want to, and I didn’t need to. He sat with me while the knives whined their siren song from the drawer and I rocked back and forth, gently, sort of ignoring them but mostly just waiting.

Kevin was there somewhere, perched in the back of my mind, reminding me that clear-cut choices are few and far between, and I had better not fuck this one up.

In Simplest Terms and Most Convenient Definitions

Lee Redmond of Salt Lake City, Utah, had the world’s longest fingernails. She stopped cutting them in 1979, and, according to the Guinness World Records website, they measured a total of 28 feet 4.5 inches by 2008. At 2 feet 11 inches, her right thumbnail was the longest of them all.

When Redmond initially secured the world record, she announced plans to cut her nails. In the August 10, 2006, edition of the

Deseret Morning News

(Salt Lake City’s more conservative paper), she described her daily activities, including grocery shopping, cooking, and taking care of her husband, an Alzheimer’s patient. She said of her nails to reporter Tammy Walquist, “It’s strange how they become you. It’s almost your identity. It’ll probably be a trauma after twenty-seven years to cut them off.” She then changed her mind, unwilling to part with them. She turned down tens of thousands of dollars to slice them down to socially acceptable length on live television.

On Tuesday, February 10, 2009, the sports utility vehicle in which Redmond rode was involved in a collision. According to the SLC police, Redmond was ejected from the vehicle and sustained serious but not life-threatening injuries. She survived, but her nails did not. Each one broke off near the finger.

When I heard about Lee Redmond’s accident, my first thought was

not

“Jesus, how the fuck do you insert a tampon with two-foot-long fingernails?” (That was my second thought.) My first thought was, “Why on Earth would anyone

choose

to be a freak?” To my mind, freaks generally come in two categories: those whose freakishness was visited upon them and those who devote considerable time and effort to creating and maintaining their freak status. I am one of the former, and I have never been able to understand the latter.

When I was a child, I began to experience panic attacks that increased in frequency and intensity over several years. This condition eventually led me to develop a fear of leaving my small studio apartment, and finally of leaving my bed—even to go to the bathroom. The ensuing complications were, well, pungent.

By the time I was twenty-one, I was a full-on obsessive, cowering, trembling agoraphobe. How serious was it? Well, because I was too frightened to go to the hair salon, I let my roots grow out—which, gentle reader, is truly a sign of desperation in a born-and-bred daughter of New Jersey.

The word

agoraphobia

comes from the Greek

phobia,

or fear, and

agora,

or marketplace. In simplest terms and most convenient definitions, my psychiatric diagnosis is that I’m afraid of the mall. Which, I can assure you, is untrue. New Jersey claims to be a state, but it is actually a gigantic slab of cement upon which malls sprout like blisters and corns on the stubby, scrubby feet of overworked, chain-smoking strippers. These malls are interconnected by a complex, ill-conceived system of congested roads. You are not allowed to take a left turn anywhere in the entire state. If you try, the rest of us will run you over on our way to the Macy’s white sale.

If you opened up my chest and examined my heart, I’m fairly certain you would find stamped therein a precise map explaining how to get from the Bridgewater Commons Mall to the low-rent Quakerbridge Mall, to the high-endiest of high-end malls, the Alpha and the Omega, the Mall at Short Hills (valet parking! Neiman Marcus! Sit-down restaurants!). I feel at home in these temples to materialism. They have many bathrooms, and if you get anxious you can always find pain-numbing food or a soothing, well-chlorinated fountain.

In fact, my own life is so entwined with mall lore and magic that everything-must-go closing sales at mall shops fill me with an unbearable sense of despair. There is nothing I despise more than a once-great mall gone to ruin, the victim of a poor economy or a competing mall in the neighboring town. These are ghost malls, and they haunt my dreams. Their stores—empty husks of commerce—are tragic reminders of our own mortality. I can’t handle the recent spate of recession-era store closings. I’m still not over Structure, and that old warhorse died over a decade ago.

I believe that there should exist an end-of-year memorial montage for all the mall stores we’ve lost. You know, like they have at the Academy Awards ceremony each year. And I believe this montage should be set to Sarah McLachlan’s “In the Arms of the Angels.” A solemn voice—mine, perhaps—should intone the names of the deceased as images of their gone-but-not-forgotten merchandise flash across the screen. “Circuit City,” I’ll whisper. “Tower Records. Virgin Megastore.” Viewers will weep. It’ll be fucking beautiful.

To sum up: my diagnosis notwithstanding, I’m not really afraid of the marketplace. Quite the opposite, in fact. But I have been afraid of many other things. Here are some of them, in a handy chart form that will get you up to speed:

When I say that I’ve been afraid of these things, I don’t mean that I had a vague idea that it would be painful or distasteful to endure them. Nor do I mean that I simply disliked these activities or concepts. Rather, I developed, to one degree or another, a terror of these events/acts/experiences. In the case of leaving my home, flying, taking the train, taking the bus, taking the subway, driving, and being a passenger in a vehicle, I developed an actual phobia. There are funny Greek names for each of these individual phobias, but it’s more convenient to group them together under the label of agoraphobia.

I didn’t just wake up one day and realize that I was an agoraphobe. For me, agoraphobia crept up after a decade of experiencing panic attacks in a diverse and exciting array of situations.

Panic attacks happen when your body shifts into an ancient and somewhat entertaining state known as the “fight or flight” response. It’s actually a good reaction to have if, for example, a bear is chasing you and it is the year 1000

B.C.E.

and you live in the woods and have only a wooden spear to protect yourself. Your heart starts beating very fast and blood flow is diverted from your extremities to your heart and upper respiratory system, so you can breathe more quickly, and your legs get tense, and you start to get nauseous, because your digestive system goes out of whack (your body isn’t going to waste time digesting your food—there’s a fucking

bear

after you! Run!), and your pupils actually dilate a little bit to let in more light in case you have to run through light and dark. In the woods. Where you live.

It’s all very evolutionary and interesting, and, like bicycles and electroconvulsive therapy, it can still be useful in some cases. For example, if you’re walking down the street late one night and are approached by someone who expresses a sincere and heartfelt desire to rape you, you should probably go into fight or flight, and run the fuck away as fast as you can. Unless you’re into that sort of thing, in which case you probably write a blog that only appeals to a very small segment of humanity.

A panic attack is the fight-or-flight response in a situation that does not require fisticuffs or the hurling of primitive weaponry. Sometimes a situation triggers a painful memory. For example, a soldier who is home from a combat zone might find that he becomes frightened and has a panic attack when he hears a news chopper flying over his city. Post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD, sometimes includes this sort of response.

Quite often, however, the panic attacks are related to a more general feeling of not being in control of a situation. Many sufferers find they have panic attacks in crowds. I once had a doozy of a panic attack while driving through the desert in Texas. Having grown up among hills and trees, I found it terrifying and more than disconcerting to actually

see

the horizon. I later spoke to a tall Texan/Native American lesbian semi-pro softball player, who had freaked out on a car ride back East when she

couldn’t

see the horizon for the trees. And if you know any Texan/Native American lesbian semi-pro softball players, you know they don’t scare easy.

Somebody who has had enough panic attacks (and “enough” can mean one or one hundred) might start to avoid the places where he or she has had those panic attacks. After all, if every time you walked into a particular store you were punched in the stomach, you’d probably find another store to visit, right? (Again, unless you’re into that sort of thing.) And thankfully, our homogenized chain-store culture enables one to find pretty much the exact same shit in half a dozen big-box outlets.

If you live in the average American town, you’ve got a Walgreens, a Rite-Aid, a CVS, an Eckerd, the drugstore at Walmart, and some local family-run pharmacy that’s on the verge of closing due to the presence of the previous five. Unfortunately for you, the mysterious impulse that causes the panic attacks is within you, not the stores. You’ll keep having those panic attacks no matter where you pick up your birth control. Eventually, there won’t be any stores left to try. (Then you’ll probably obtain it using the agoraphobe’s greatest friend: the Internet. But you might miss actual human interaction after a while.)

For me, it was approximately a decade-long trip from “I’m afraid of X” to “I’m afraid of other places that look like X” to “I’m afraid of every place that is not my bed, and have resolved to stay there for the rest of my life, thank you very much.” I prayed that this mysterious mental malady would be lifted from me spontaneously, or that I would somehow suddenly become normal. It didn’t happen.

When I was twenty-one I finally concluded that I was a freak of the most terrible type, designed not to be displayed and celebrated but to be hidden in the darkness, an ugly, stinking waste of flesh. If college was supposed to be the best time of my life, I couldn’t imagine how awful it must get afterward. It sure didn’t seem like the sort of thing worth sticking around for. I wondered how it had taken me so long to realize that I was broken beyond repair, and that I didn’t belong on this planet with all of the real humans. I imagined my future as one of dependence, fear, and disability. I would always be a burden on the saner individuals charged with my care. I would always be different, in a bad way. I might kill myself, if only I could summon the courage to choose death. Instead, I chose to do nothing but wallow in the rising swamp of my own shame. I hid in my bedroom, with garbage piling around me, rocking back and forth in bed, singing an old, half-remembered hymn as I prayed for sleep to come and blot it all out.

Of course there had been warning signs—plenty of them, over the years. Maybe I was too young or naive to recognize them, too afraid to speak up and admit that I needed more help. My brain sent up one big, giant, flaming-red signal flare when I was eighteen, the week after the beautiful boy from summer camp killed himself. But everybody around me found ways to explain it away. It was heat exhaustion; it was fatigue; it was homesickness. After all, no one goes crazy on vacation.