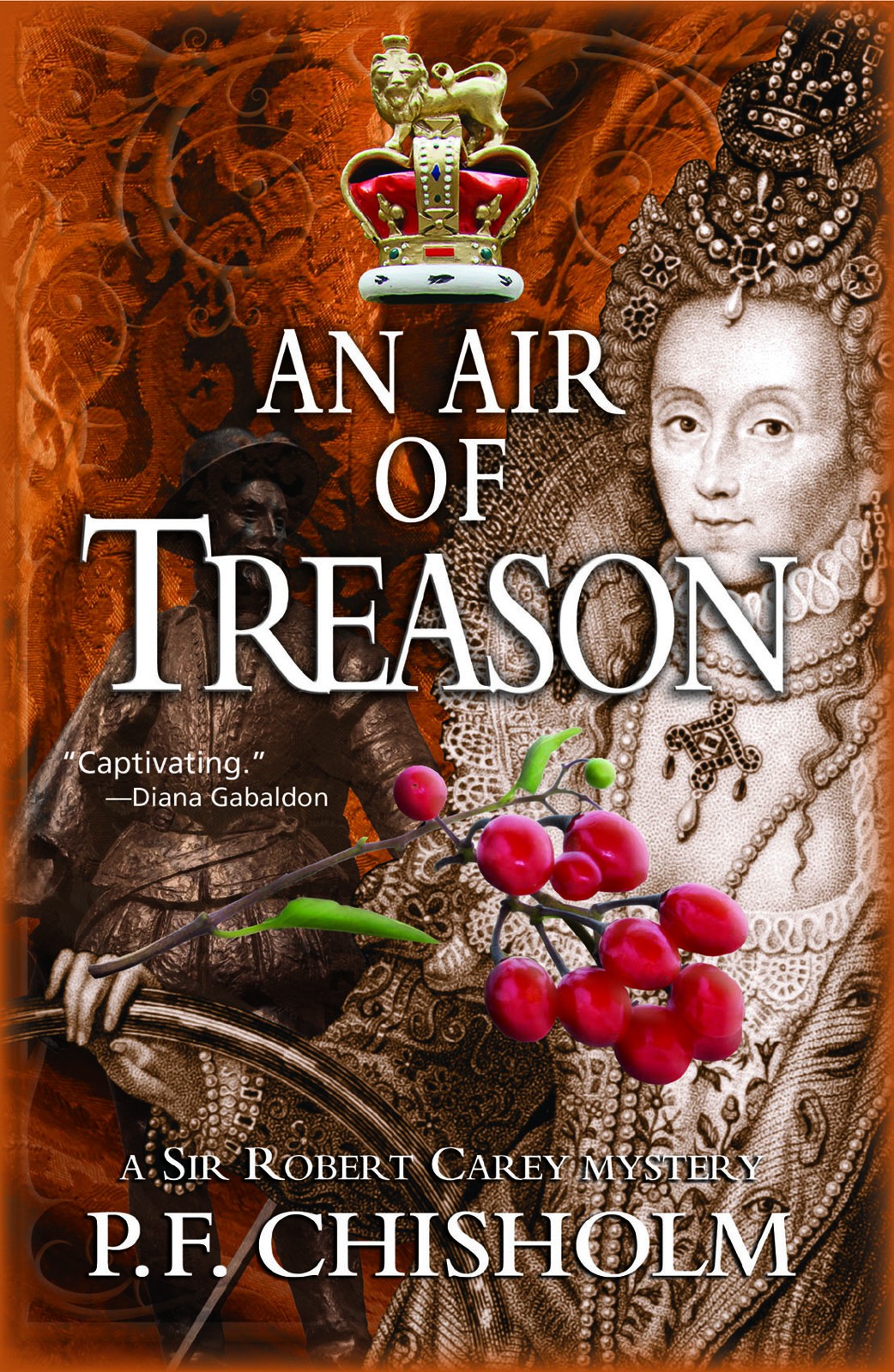

Air of Treason, An: A Sir Robert Carey Mystery (Sir Robert Carey Mysteries)

Read Air of Treason, An: A Sir Robert Carey Mystery (Sir Robert Carey Mysteries) Online

Authors: P. F. Chisholm

Tags: #MARKED

An Air of Treason

A Sir Robert Carey Mystery

P. F. Chisholm

Poisoned Pen Press

Copyright © 2014 by P. F. Chisholm

First E-book Edition 2014

ISBN: 9781615954728 ebook

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in, or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise) without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

The historical characters and events portrayed in this book are inventions of the author or used fictitiously.

Poisoned Pen Press

6962 E. First Ave., Ste. 103

Scottsdale, AZ 85251

Contents

This book is dedicated to my wonderful band of beta-readers who save me from making even more mistakes than I actually do and in particular to:

Kendall Britt and

Sallie Blumenauer

who tell it as they see it and immeasurably improve every book they read for me.

Many many thanks.

Saturday 16th September 1592, morning

It was the devil’s own job, it truly was, thought Hughie Tyndale. How the hell had he agreed to it? Why had he agreed to it?

The internal voice that never missed a chance to jeer at him was quick with an answer. So ye wouldna hang, it said, why else?

“I’ll hang if I manage it,” Hugh said back to the jeering voice.

The jeering voice said nothing because this was plainly true. If you got caught killing someone, you generally hanged. All the more if they found out why you were killing him, which they probably would if they used the boot or the pinniwinks or whatever it was the English authorities used when they urgently wanted to find out something. And killing a cousin of the Queen would most certainly draw their attention.

He’d tried before to get close to the man he was to kill and failed miserably. Several times. That time in St. Paul’s Walk by Duke Humfrey’s tomb. The place had been crowded despite the plague running through London. It was full of ugly men in worn jacks, while Carey the Courtier, the man he was supposed to kill, had wandered by dressed in many farms’ worth of velvet and pearls, deep in conversation only a yard away.

Of course he hadn’t been intending to do the killing out in public. The first part of the plan was to go to work for the man, find out everything about him and pass it on to Scotland. How? He didn’t know, but someone would tell him, apparently. Then he would do the killing and if he could get away in time, he’d be free as a bird. That was according to the mysterious man who said he worked for the Earl of Bothwell. When the funeral had been held, Hughie could visit a certain goldsmith in London town and receive a pile of gold. Allegedly.

Hughie shifted his weight and consciously straightened his back. He’d do it, of course he would. He wouldn’t hang; he’d be rich. So now he wondered how he could be sure he stood out among all the mob of unemployed servingmen under the Cornmarket roof—without being so obvious about it that he tipped off the Courtier. Bothwell’s man had warned him, the Courtier is a lot cleverer than he looks or sounds.

Oxford Cornmarket, with its smart lead roof held up on round pillars down the centre of the street, was packed with men and quite a few women, people having come to the hiring fair from villages and towns for miles around. The Queen and all her Court and baggage and hangers-on were at last only seven days away. The city fathers and the university were in the last contentious stages of setting up the elaborate expensive pageantry of welcome. No doubt most of them were in meetings, speechifying at each other.

The whole of Oxford seemed to be armoured with scaffolding. The streets were clean for the first time in twenty-four years, and some of them were being newly paved, some boarded over.

A college steward was standing on a box, shouting aloud from a list.

“I want eight carpenters, four plumbers, five limners, eight labourers for college of Trinity,” he bellowed. “Thruppence a day until the Queen leaves, a bonus from my Lord Chamberlain if all work is done before the Queen arrives, another bonus if nothing is amiss when she leaves.”

Those were good terms. Some of the men standing around Hughie shifted toward the steward, even though several of them didn’t look like skilled men but like simple bruisers.

A few of the girls were surrounding a stout woman on another box, roaring her needs—laundresses, sempstresses, confectioners, cleaners. An entire new city was foisting itself awkwardly on the scholarly city of Oxford, like an eagle on a blackbird’s nest.

Hughie backed a little to the wooden pillars of the smart merchant’s house next to the church. Most of the men there were quite a bit smaller than him and a few looked at him sideways.

His quarry would come, of course he would. The Courtier needed at least one henchman and Hughie would be perfect for him. Where else was he going to find so cheap a servingman with Hughie’s abilities?

Hughie scanned the better-dressed men walking around amongst the people for hire. Most were stewards and college bursars, narrow-eyed, tight-pursed. A few were clearly harbingers for the Queen or the greater lords.

Hughie knew the Courtier was in town for sure, and would probably leave again on Sunday afternoon. Possibly earlier. He had arrived late on Friday night, dressed in hunting green with one spare mount and a lathered pony heavy-laden with packs. That was quite impressive, Hughie had to admit. It was more than forty miles from London to Oxford and he hadn’t really been expected so early—Hughie had been carefully buttering up Lord Chamberlain’s steward and making himself pleasant to the minor officials of his household on the assumption the quarry would travel with his father.

No, according to the horseboy Hughie had been paying on retainer at the main carter’s inn near Christ Church, the man had arrived Friday night, both horses and the pony exhausted, at around seven o’clock. Forty miles in a day—despite the heavy cart and pack horse traffic on the Oxford Road—meant he must have been using the higher causeway reserved for the Queen’s messengers, and galloping at least half the time. The man himself was tired but quite alert enough to make sure Hughie’s helper carried the heavy packs up to his room and then was tipped a sixpence to guard the door. The Courtier saw the host, paid for the room, and ate the ordinary for his dinner.

He had no henchmen with him, not one. Not even the surly-looking borderer who had been shadowing him in London. So it stood to reason that he would be in need of at least one follower. At least one.

Hughie peered through the shadowed forest of humanity again. He had to be there, where else would he find a servingman? He had to come.

“What’s your name?” came a snappy voice beside him.

It wasn’t the Courtier. Hughie looked as nervous and as thick as he could. “Oh ah, Hughie, an’ it please yer honour, Ah’m a…”

The steward tutted and passed on immediately. It was Hughie’s accent, he knew that. Not only was it a harsh voice, like a corncrake, but you could easily hear in it that his first language was Scotch not English. And although cheap, the Scotch were notoriously dangerous employees.

Someone who had been leisurely buying a pie from a nicely shaped girl under the portico opposite, spun round to look at him.

God above, it was him! Hughie did his best not to stare, modestly looking at the ground. The man was well-built, tall, chestnut hair under his hat and a goatee beard that needed trimming, extremely bright blue eyes and beaky nose, and a breezy manner that breathed of what he was and what he thought of himself.

Carey the Courtier was first cousin to the Queen in two different directions, one of them firmly on the wrong side of the blanket, according to Bothwell’s man’s clerk. His father’s coat of arms said so proudly, boasted of it in fact, blazoned with three Tudor roses. You couldn’t hardly put it plainer, the clerk had sneered, and the English heralds had allowed it, the scandalous Papistic perverts.

This was the man he had to kill: Sir Robert Carey, youngest son of the Lord Chamberlain, Baron Hunsdon, connected by blood and marriage with half the Court as well as the Queen. Carey was currently a controversial deputy warden on the English West March, where he was interfering in things that didn’t concern him.

Mind, he hadn’t looked quite so full of himself the time he’d been pointed out to Hughie at the Scottish Court, but that had been in the summer and he’d had a stressful few days there.

Carey did seem a little worried and he hadn’t seen a barber for a couple of days either. Would he remember the disastrous last time Hughie had made a play to work for him? That was the point. God, those musicians had been angry.

Carey had come over and was standing in front of Hughie, looking him up and down.

“Quhair are ye fra?” he asked in passable Scotch.

That shouldn’t have been a surprise to Hughie, yet it was. He stuttered.

“Ay…ah…Edinburgh.”

“Quhat are ye at sae far fra yer ain country?”

“Ah’m trying to get maself home, sir,” said Hughie, getting ahold of himself, switching to English and straightening his spine.

“Oh?” One of the man’s eyebrows had gone straight up his forehead.

“Ah come south on a ship wi’ a merchant, but we had a falling out and Ah’m heading north now.”

Carey came closer and looked Hughie up and down again, carefully. He stood still for it, feeling a blush coming up his neck.

“What’s yer trade?”

“Ma dad wis a tailor, sir, I prenticed tae him but it didna suit me well.…” That had been his uncle Jemmy, not his dad but no matter, near enough.

The other eyebrow went up and Carey crossed his arms and started stroking his goatee thoughtfully. “Did you grow too tall to sit sewing all day?”

Och thank God, thought Hughie, excitement rising in him. Is it working? Is it really working?

“Ay, sir.” It was quite true he had got too tall. Sitting cross-legged all day had cramped him something dreadful, though not as much as frowsting about indoors all the time. “Once Ah grew and got my size, I couldnae stick the tailoring, so I prenticed wi’ a barber for a while and then after I got…ah…intae a wee spot of bother…I hired on as a merchant’s henchman to come south, sir.”

Carey beckoned Hughie to turn his head and lift his hair. Ah, yes, looking for a ragged ear from having it nailed to the Edinburgh pillory for thieving. No, Hughie’s ears were still the shape God had given them.

“What was the spot of bother?”

This was the lie absolute, the only one completely adrift from the truth.

“It wis a riot, sir, in Edinburgh, after a football match. Ah killed a man and the procurator banished me from Edinburgh for a year and a day.”

“Hmm. How did you kill the man?”

Hughie improvised. “Ah hit him on the head with an inn table, sir.”

Carey nodded, looking cynical. It struck Hughie that lying about it was actually fine, so long as he could come up with a more believably serious killing-method when he needed it. Only not as serious as it had actually been, of course. Carey wouldn’t hire him if he boasted about killing his uncle.

Hughie knew he was too saturnine and large to be able to look innocent and so he settled for looking hopeful. Come on, man, Hughie begged silently, thinking of the pile of gold that would be his when he’d done the job. I’m what you need. Come on.

The man had his head on one side, appraising Hughie with his eyes narrowed. “Do you know who I am?” he asked.

“Ah, no, sir. Sorry, sir.”

“What’s your name?”

“Hughie Tyndale.”

“Like the translator of the Bible in King Henry’s reign?”

“Ah…maybe, sir?”

Who the hell was that? Hughie thought. He used the name Tyndale because he wasn’t inclined to tell them his right surname and that was where his family came from originally. “Ah dinna ken…”

“No matter. So you’re looking for a master who might take you north?”

“Ay, sir.” He risked it. “And disnae mind ma voice.”

Carey nodded absently. He seemed to be thinking, appraising Hughie again. There was a faint frown on his face. “Have I ever met you before? I was in Edinburgh as a young man.”

“Ah…” Oh God, oh God, he’d remembered. “Ah…when was it, sir?”

“Oh, about ten years ago now.”

“Och, Ah wisnae mair than a lad…”

“Yes, of course. Or perhaps one of your family?”

“Perhaps, sir.”

Hughie’s stomach was getting tighter and tighter. This might work. The Courtier hadn’t turned away. It might work. Please God, let it work.

The man in front of him in the mud-splashed hunting green and long boots, laughed and slapped his fine gloves on the palm of his hand.

“So you know how to tailor and barber and you can fight?”

“Ay, sir. That I can.”

“Fourpence a day, all lodging and food found. Will that do you?”

“Ay, sir?” Hughie heard his voice tremble. It wasn’t riches, but it wasn’t bad, a whole penny a day better than labouring, which he’d done before and didn’t like. “Ah, sir, that’d be fourpence a day English?”

Carey laughed again. “Oh, yes. I might even be able to get you some livery if my father’s feeling generous.”

“Ay, sir?” It was working. “Ay, that’s verra…ah…very good, sir.”

Carey stripped off his right glove and his right hand came down on Hughie’s right shoulder and gripped. Hughie looked down at it, with the bright golden ring on it and a couple of nails almost regrown.

“Excellent! Do you, Hughie Tyndale of Edinburgh town, swear to serve me faithfully according to my commands within Her Majesty’s law and your right honour, so help you God?”

“Ay, sir, I do.”

“Then I, Robert Carey, knight and deputy warden of Carlisle, swear to be your good lord as long as you serve me well, so help me God.”

They spat on their palms and shook hands. It was the old-fashioned way, the way of Hughie’s grandfather, when the duties had gone in both directions from man to master and back again. Hughie felt a vast golden bubble of relief escaping from his lungs. No matter that he’d sworn fealty to the man he was to spy on and, in due course, kill. He’d sort it out with God later. God would surely understand that he had no choice.

Saturday 16th September 1592, noon

The first thing that Hughie Tyndale found after becoming Sir Robert’s henchman was that he hadn’t been walking fast enough. He kept getting left behind as Carey forged through the crowds of the hiring fair to the desk at the centre where the master of the fair kept his register. Carey signed his name and paid the tax, Hughie made his mark. He could in fact write but he had decided long ago not to make too much of that.

“Can you read?” Carey asked him when he saw the mark.

“Ay, sir,” Hughie said. “Ma dad put me tae the Dominie to learn ma letters.”

“Good, read that,” said Carey pointing at the words of the indenture the clerk was writing up three times. Hughie struggled through the easier words despite some of it being in some kind of foreign.

“Hmm, creditable,” said Carey as the clerk tore the indenture in three, gave Carey one part, Hughie himself the other part, and kept the third. It was for a year and a day from the hiring fair, plenty long enough to do what Hughie had to. On the other hand, making it official in the modern way as well meant that killing Carey would be petty treason and he might burn for it. If he got caught, of course, which he wouldn’t.