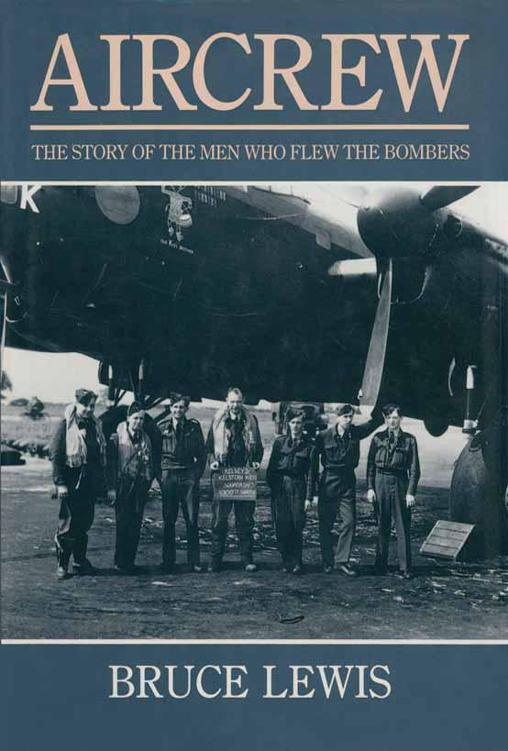

Aircrew: The Story of the Men Who Flew the Bombers

Read Aircrew: The Story of the Men Who Flew the Bombers Online

Authors: Bruce Lewis

Aircrew

By the same author

The Technique of Television Announcing

Four Men Went to War

Aircrew

The Story of the Men

Who Flew the Bombers.

Bruce Lewis

LEO COOPER

LEO COOPERLONDON

First published in Great Britain in 1991

by Leo Cooper, 190 Shaftesbury Avenue, London WC2H 8JL

an imprint of Pen & Sword Books Ltd., 47 Church Street,

Barnsley, S. Yorks S70 2AS.

Copyright © Bruce Lewis, 1991

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 0 85052 4474

Phototypeset by Input Typesetting Ltd, London SW19 SDR

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Mackays of Chatham

To Miki with Love

Contents

ABC:

Airborne Cigar. Powerful transmitters carried by Lancasters of 101 Squadron to jam enemy instructions to Luftwaffe night fighters.

ASI:

Airspeed Indicator.

ATA:

The Air Transport Auxiliary whose pilots, both men and women, ferried aircraft from the factories to the squadrons.

Bullseye:

Code name for participation by an OTU trainee crew in a bombing raid. Often with a ‘screen’ or experienced pilot.

Circuits and Bumps:

A training exercise in which a pilot took off in an aircraft, circled the airfield and landed – repeating the exercise over and over again until he was completely familiar with the flying characteristics of that particular machine.

Cookie:

The standard 4,000 lb blast bomb carried by RAF Bomber Command. It was an unstreamlined drum made from thin mild steel and filled with molten RDX explosive. The casing made up only 20% of the weight. There was also an 8,000 lb version.

DR:

Dead Reckoning; basic navigation without the help of radar or radio aids.

ETA:

Estimated Time of Arrival.

FIDO:

Fog Intensive Dispersal Operation. Pipes laid either side of the runway had petrol pumped through them under pressure. This was ignited and blazed upwards through perforations in the pipes. It was an effective, if costly, method of dispersing fog in the vicinity of the airfield.

Freya:

Luftwaffe code for their ground radar used to detect approaching bomber forces.

Gee:

Bomber-navigation radar, dependent on pulses received from ground stations in England.

George:

Automatic pilot.

Grand Slam:

22,000 lb bomb. The largest bomb ever carried in

World War Two. Designed by Barnes Wallis, only the Lancaster could deliver it.

Ground Cigar:

Powerful transmitters sited in England and manned by German-speaking operators, men and women, broadcasting false instructions to enemy night fighters.

H2S:

The first self-contained airborne navigational radar needing no ground stations.

IFF:

Identification Friend or Foe. An automatic transmitter giving aircraft a distinctive shape or ‘blip’ on a radar screen, distinguishing it from enemy ‘blips’.

Kammhuber Line:

Named after its instigator, Generalmajor Josef Kammhuber, it was a defensive line of searchlights, flak guns and ground-controlled night-fighters, stretching from Denmark in the north down the entire length of the enemy-occupied coast. It finally comprised over 200 separate ‘boxes’ each with is own control centre. British bombers had to pass through this defensive screen both on the outward leg, and when returning from a raid.

Knickebein:

(Crooked Leg). Code-name for a system of radio navigational beams used by the Luftwaffe to bomb British cities at night in 1940. By the autumn of that year British scientists had learned the secrets of its operation and introduced counter-measures which included ‘bending’ the beam.

Lichtenstein

or

Li:

Luftwaffe code for their AI (Airborne Interception) radar equipment.

LMF:

Lack of Moral Fibre. A cruel tag applied to aircrew who could no longer face up to the demands of operational flying.

Monica:

Code-name for radar equipment used in RAF bombers to detect enemy night-fighters approaching from the rear. Hastily discontinued when it was discovered these same night fighters were ‘homing in’ on Monica’ s radar emissions.

MU:

Maintenance Unit.

Naxos:

Luftwaffe code for their version of ‘Serrate’.

Nickels:

Leaflet raids carried out in the early stages of the war. Operations known cynically in the RAF as ‘Bumphleteering’.

Oboe:

Radio beam navigation system. Two ground stations transmitted beams which intersected at the target. It was so accurate that crews could bomb ‘blind’ with it, but it was limited in range to about 350 miles. Effective over the industrial haze of the Ruhr.

OTU:

Operational Training Unit. Originally the last stage before joining a squadron, but later becoming, at most, the penultimate state, when …

HCU:

Heavy Conversion Units were introduced. At these crews were familiarised with the big four-engine bombers, usually Halifaxes. There was a further stage at…

LFS:

Lancaster Finishing School, for those crews fortunate enough to be selected to fly ‘Lanes’.

Perfectos:

Refined radar equipment fitted in night intruder Mosquitoes which triggered the Luftwaffe version of IFF signals in their night-fighters. The successor to Serrate.

RDF:

Radio Direction Finding.

Serrate:

Radar receiver used for detecting German night-fighter radar emissions and carried by night intruder Beaufighters. SABS: Stabilizing Automatic Bomb Sight.

Ship:

American term for an aircraft.

Special Operator or ‘Special’:

The eighth member of crews flying with 101 Squadron. German speaking, the Special operated ABC equipment.

Tallboy:

12,000 lb deep-penetration ‘earthquake’ bomb. Also the brain-child of Barnes Wallis, Lancasters of 617 Squadron were specially adapted to the job of carrying it.

Tame Boar, (Zahme Sau):

German code name for infiltration of the bomber stream by twin-engine night-fighters, Messerschmitt 110s and Junkers 88s. Guided into the stream by ground control, the interception was then carried out by the individual aircraft using their Lichtenstein radar.

U/S:

Unserviceable. Occasionally caused misunderstanding among servicemen from the United States.

WAAF:

Women’ s Auxiliary Air Force. Members of this force participated in most of the RAF skilled trades except flying.

Wild Boar, (Wilde Sau):

German code name for Luftwaffe night-fighters, (often single-engine day fighters pressed into night service), which massed high over the target to pick off RAF bombers silhouetted by the searchlights and flames. This method was rapidly introduced by the Germans after the dropping of ‘Window’ over Hamburg in July, 1943, scrambled their radar systems.

Window:

Metal strips cut to the same lengths as the wavelengths of German ground radar transmitters. When dropped from bombers

at regular, timed, intervals it could either swamp the enemy radar screens, or, used more selectively, create a false impression of a major raid approaching, and even, as on D-day, simulate the advance of a vast seaborne invasion.

Wurzburg:

Code-name for two versions of Luftwaffe ground radar control systems. The smaller of the two installations was used to direct master searchlights and flak guns, while

Wurzburg Reise

, (Giant Wurzburg), accurately detected individual bombers, the information then being passed to night-fighters equipped with Lichtenstein.

X-Verfahren:

Code-name for a more advanced system of radio navigational beams operated by Heinkel 111s of Kampfgruppe 100, acting as pathfinders to the main force. Most successful on the raid against Coventry, it was afterwards rendered less effective by British countermeasures. (This system is often wrongly referred to as

X-Gerat

, a term which covered the airborne equipment only).

I am aware of the number, some would say plethora, of books that have been published on the subject of the Allied Bombing Campaign in Europe during the Second World War. Many of these concentrate in detail on the strategic and tactical aspects of this campaign, and also on the remarkable application of radar that made possible the successful bombing of Germany by night. I have learned a great deal, particularly about high level policy, from reading carefully researched publications, often written by authors who were not even born at the time.

However, as one who flew with Bomber Command, and who retains an undying respect for my companions of those days, I sometimes feel, because of the way the subject is presented, that there is a danger of the ‘machine’ and the ‘electronic wizardry’ taking precedence in people’ s minds over the human beings who actually crewed the bombers. To say, for example: 57 of our aircraft failed to return on 21/22 January, 1944, is rather different from reporting that over 400 airmen were lost on that night.

So, in an attempt to redress the balance a little, this book is a combination of first-hand experiences told to me by a number of one-time aircrew members, mixed with a few personal memories, and a background filled in by a fair amount of research. Overall, I hope it throws some light on the tasks that these young volunteers undertook, and which they fulfilled to the best of their ability under terribly dangerous circumstances.

I have included a section on the exploits of men of the United States 8th Army Air Force in addition to those of the RAF’ s Bomber Command – we were all airmen who flew to war over Europe in the ‘Heavies’, and were in it for the same purpose – to kick out the Nazis.

Many thanks to all those kind people who made this book

possible, including that painstaking historian, Martin Middle-brook, who has generously allowed me to refer to his definitive work

The Bomber Command War Diaries

. Also the staff of The Memorial Library Second Air Division USAAF for giving me so much help during my visit to Norwich. I am grateful for Mr Andrew Renwick’ s careful guidance in the Photographic Department of the RAF Museum, Hendon, and to his colleague, Mr David Ring, who rendered valuable help at the eleventh hour. Lastly, and particularly, those ‘ex-bomber types’, who told me, without a trace of self-promotion, what happened to them while flying in the wartime skies over Europe.

Bruce Lewis

In The Beginning

It was my 18th birthday when I walked into the recruiting office and volunteered for Flying Duties with the Royal Air Force. Bomber Command had already been fighting a lonely, bitter war against Germany for over two years and was, at that time, going through a bad patch. Aircraft losses were mounting and results were disappointing. In Britain many powerful voices were murmuring that the money lavished on the bomber offensive could be better spent elsewhere in the pursuit of victory. I, of course, like the rest of the British public, knew nothing of these political undercurrents.

Most of us who were to fly in the four-engine ‘Heavies’ – the Lancasters and Halifaxes that sustained the great onslaught against the enemy in the later years of the war – were either still at school, or starting out on our first jobs, when war was declared against Germany on 3 September, 1939.