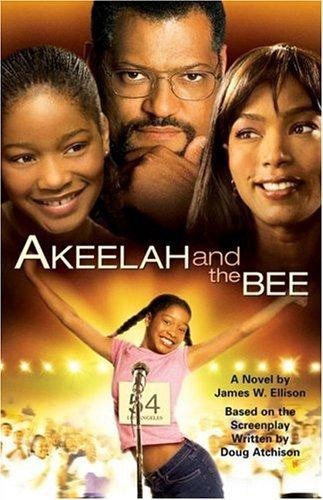

Akeelah and the Bee

Table of Contents

The Present

Akeelah Anderson, small and skinny for a just-turned-twelve-year-old and smart beyond her years, sits in her bedroom staring at her image in the mirror and engaging in one of her favorite pastimes: daydreaming. She removes her glasses, cleans them on the sleeve of her blouse, then replaces them in a single, flowing, absent-minded movement. Slowly her image breaks into a smile.

“Akeelah,” she says in a surprisingly low voice, given her age and slight physical stature, “what a journey for a girl from South Los Angeles. Girls from this neighborhood just aren’t supposed to have journeys like this. Everything seems like a dream. I know this happened and that happened and a whole bunch of other things, too, but it should seem more real than it does. What’s the word for what I’m feeling? Come on, girl, words are what you’re good at. What is it you’re reaching for? ‘Verisimilitude’? ‘Somnambulism’ ? ‘Déjà vu’ ? Nope—they’re all wrong. But there’s gotta be a word for it because it’s how I’ve been feeling all year and it just doesn’t go away….”

She sticks out her tongue and crosses her eyes. “You’re crazy, girl, plain loco, talking to yourself this way. If you start answering yourself, you’ll know you’re in big, big trouble.

“Maybe the word I’m searchin’ for is… what? Maybe it’s ‘magic. ’ Human magic….”

One

The Anderson family—mother, two sons, and two daughters—lived in a mostly black neighborhood in South Los Angeles, a dangerous, forlorn area that often erupted in violence, especially on Saturday nights and most especially on the hot nights of summer. It was light-years removed from the glitter and glamour of Hollywood and the majestic coastline to the west. Akeelah attended Crenshaw Middle School, an unkempt institution with gang graffiti scrawled on the walls. There were dangling pipe fixtures in the bathrooms where, in better times, the sinks used to be. African-American and Hispanic kids crammed into the overflowing classrooms, shouting, cursing, pushing one another, and ignoring the teachers who implored them to quiet down and take their seats. The teachers, for the most part, were tolerated but not obeyed. Already at ten, eleven, and twelve, many of the students at Crenshaw resented any official forms of discipline and fought against them with street anger and street smarts.

Ms. Cross, a petite teacher in her early forties, with lines of worry etched in her features, walked down a row of desks occupied by rowdy seventh-graders. Like all the classes at Crenshaw Middle School, Ms. Cross’s was overcrowded. There were nearly forty students jammed into a

small space. They all wore school uniforms, and many of the girls were already wearing makeup. Ms. Cross handed out graded spelling tests. She tried to put on a smiling face, but gave up the effort as the noise level increased.

small space. They all wore school uniforms, and many of the girls were already wearing makeup. Ms. Cross handed out graded spelling tests. She tried to put on a smiling face, but gave up the effort as the noise level increased.

“You’re all in the seventh grade now,” she said. “What does that mean to you?”

“It mean we be in the eighth grade next year,” said a tall boy lounging in the back of the room.

“Not necessarily, Darian,” the teacher said. “What it means is, when I give you a list of words, you

study

them. Middle school means taking more responsibility. The average score on this test is very upsetting—barely 50 percent. Totally unacceptable. I know you can do better, but you have to work at it….” She paused in front of Akeelah’s desk. Akeelah was busy whispering with her best friend, Georgia.

study

them. Middle school means taking more responsibility. The average score on this test is very upsetting—barely 50 percent. Totally unacceptable. I know you can do better, but you have to work at it….” She paused in front of Akeelah’s desk. Akeelah was busy whispering with her best friend, Georgia.

“Akeelah,” Ms. Cross said, “I hate to break into your very private conversation.”

She turned to the teacher and said, almost under her breath, “That’s sarcasm, ain’t it, Ms. Cross?”

She tried to restrain a smile.

“I guess you could say that. Tell me something. How long did you study for this spelling test?”

Akeelah shifted her eyes uneasily to some of her classmates who were following this exchange intently. She knew what lay behind the teacher’s question and she didn’t like it. In Crenshaw Middle School the wisest course was to remain anonymous, not to stand out, and above all, never to appear smarter than the other students.

And even above that, it was important never, ever to be labeled as the teacher’s pet.

And even above that, it was important never, ever to be labeled as the teacher’s pet.

She said with a shrug, “I didn’t study for it.”

The teacher looked at her with surprise, an eyebrow lifted. “You didn’t?”

“No, ma’am.” She looked bored and uninterested, a pose she had developed in the past year as protective covering. Being smart was dangerous. She had learned that lesson the hard way, having accumulated in the past year a collection of bruises and bloody noses.

Ms. Cross slapped the test facedown on her desk.

“See me after class,” she said.

Akeelah reached for the test and then pulled her hand away. “Why? I ain’t done nothin’ wrong.”

“There’s some things I have to discuss with you.”

Akeelah turned to Georgia and giggled. The moment Ms. Cross walked away and the eyes of her classmates were no longer on her, Akeelah casually lifted up a corner of her test. 100 percent. Thirty words and thirty perfect spellings. When Georgia tried to sneak a look, Akeelah covered the test with her hand.

When the bell rang there was a stampede for the door to see who could escape first. Akeelah sat at her desk until the room was completely emptied out and then slowly approached Ms. Cross’s desk. Through the small window in the door, Georgia tried to get her attention, but Akeelah ignored her.

The teacher looked up and studied her solemnly. “You’re not telling the truth.”

Akeelah went into an indignant hip-locked stance. “What do you mean?”

“You did study for the test, didn’t you?”

“It don’t make no difference if I did or not. It’s just…I wish you wouldn’t ask me stuff in front of the others.”

Ms. Cross regarded her for a moment, slowly nodding her head. “You don’t like to call attention to yourself, do you, Akeelah?”

She looked away and pressed her lips together in silence.

“You know,” she said, “you could be one of my very best students—probably

the

best. But I keep asking myself, Why aren’t you? What’s holding you back? You don’t turn in half your homework, and sometimes you don’t even show up for class. So what’s going on?”

the

best. But I keep asking myself, Why aren’t you? What’s holding you back? You don’t turn in half your homework, and sometimes you don’t even show up for class. So what’s going on?”

Akeelah shrugged. “I don’t know.”

“I have a feeling you do know.”

“Maybe I’m not as smart as you think I am.”

“But you are. Does the work bore you?”

“Yeah. It’s kind of boring.”

“Would you like it if I gave you advanced assignments ?”

“I don’t know.”

She spotted Georgia staring through the window making faces at her and started to giggle.

“Please,” Ms. Cross said, clearly frustrated. “Try to pay attention.”

Reluctantly Akeelah turned back to her. “Sorry.”

The teacher cleared her throat, swiveled a pen around

between her thumb and first finger. Finally she said, “Akeelah—do you know about next week’s spelling bee?”

between her thumb and first finger. Finally she said, “Akeelah—do you know about next week’s spelling bee?”

“No.”

“It’s been posted on the bulletin board for weeks.”

“I don’t pay no attention to the bulletin board.”

“Well, I think you should sign up for it.”

She handed her a flyer for Crenshaw’s Inaugural Spelling Bee. Akeelah’s eyes swept over the flyer, then she let out an annoyed breath.

“I’m not interested.”

“But why? You have a real talent for spelling. Some of the words on the test I gave you were very, very difficult—‘picnicking,’ for instance.” She smiled. “I misspelled that in college.”

“‘Picnicking’ wasn’t hard, Ms. Cross,” she said. “None of the words were really hard.”

“Which is why you should be in the spelling bee.”

Akeelah gave a barely perceptible shake of her head.

“Can I go now?” she said.

A very disappointed Ms. Cross stared after her as she slung her book bag over her slender shoulder and left the classroom.

Akeelah and Georgia, both of whom had seen the movie

Hustle & Flow

the week before, walked home from school singing “It’s Hard Out Here for a Pimp,” laughing and snapping their fingers. The South Los Angeles neighborhood was grim but they were hardly aware of the boarded-up storefronts, the walls crawling

with gang graffiti, the broken windows and sidewalks, and the littered streets. They had grown up in South Los Angeles and it had always been the same. They expected nothing from it, and it gave them nothing in return.

Hustle & Flow

the week before, walked home from school singing “It’s Hard Out Here for a Pimp,” laughing and snapping their fingers. The South Los Angeles neighborhood was grim but they were hardly aware of the boarded-up storefronts, the walls crawling

with gang graffiti, the broken windows and sidewalks, and the littered streets. They had grown up in South Los Angeles and it had always been the same. They expected nothing from it, and it gave them nothing in return.

Georgia and Akeelah had been best friends since they were toddlers. Georgia was kind and easy-going, and one secret of their friendship was that Georgia accepted Akeelah for who she was—a really smart girl. She was proud of her friend and Akeelah knew it.

“Devon home on leave, right?” Georgia said when they had exhausted the hip-hop song.

“Yeah,” Akeelah said. “He’s got a two-week leave.”

Devon, her twenty-year-old brother and the pride of the family, was in training to become a pilot. Akeelah had felt sad when he left for the service. With her father gone, Devon was the one significant adult male in her life.

“Your brother fine,” Georgia said. “I got it all figured out. One day he gonna be the pilot of a big commercial jet and I’m gonna be the flight attendant.”

Akeelah nodded, barely paying attention. Her mind kept returning to her conversation with Ms. Cross. Why was she pushing her so hard? She was a good speller, but why would she put herself in the position of being the school nerd—a freak for others to stick pins in? No way….That was not going to happen.

They passed a weathered-looking man hanging outside a liquor store. He was suffering from the shakes. His skin was the consistency of old leather, full of fine cracks and fissures, and his breathing sounded like steam escaping from a leaky pipe. He had been hanging out on the

street as long as Akeelah could remember, and he symbolized for her all that was wrong with South Los Angeles.

street as long as Akeelah could remember, and he symbolized for her all that was wrong with South Los Angeles.

“Got any change for an ol’ man, girls?”

Akeelah noticed that the whites of his eyes when he gazed at her were not white but the color of egg yolks.

“You wouldn’t be so old if you stopped drinkin’ that Night Train Express.”

He shook his head.

Georgia said, “Leave Steve alone. He’s a good ol’ guy.”

Steve blinked rapidly and grinned. He was missing most of his bottom front teeth.

Georgia giggled as Akeelah kicked a soiled grapefruit half and two Budweiser cans off the sidewalk.

“This neighborhood is

wack

,” she said as she reached in her purse and withdrew two quarters and placed them in Steve’s outstretched, trembling hand. “Hey, drink yourself stupid, ol’ man. Maybe that’s the only answer around here.”

wack

,” she said as she reached in her purse and withdrew two quarters and placed them in Steve’s outstretched, trembling hand. “Hey, drink yourself stupid, ol’ man. Maybe that’s the only answer around here.”

Georgia shook her head. “Girl, you always trippin’.”

As they reached the corner, a new Ford Explorer passed by, a rap song pumping full blast from the stereo. A young black man, Derrick-T, was behind the wheel. He gave the girls a wave and a grin. Derrick-T was famous in the neighborhood for the quick fortune he had amassed dealing drugs. Akeelah disliked him, certain he was a bad influence on her fourteen-year-old brother Terrence, who aped Derrick-T’s clothes and mannerisms and took great pride in riding up front with him.

“Dang,” Georgia said, “Derrick-T’s new ride is

tight

.”

tight

.”

“He been tryin’ to get Terrence in trouble.”

“Come on, Kee. Your bro can get his own self in trouble.”

Other books

Willing Victim by Cara McKenna

Cup of Gold by John Steinbeck

The Rebellion of Yale Marratt by Robert Rimmer

Talon: The Windwalker Archive (Book 1) by Michael Ploof

Mirror: Book One of the Valkanas Clan by Noelle Ryan

Caught Up in Us by Lauren Blakely

The Setting Lake Sun by J. R. Leveillé

House That Berry Built by Dornford Yates

A Magic Crystal? by Louis Sachar

How Do You Like Your Blue-Eyed Boy? by Barry Graham