Alexander Hamilton (85 page)

Read Alexander Hamilton Online

Authors: Ron Chernow

Tags: #Statesmen - United States, #History, #Presidents & Heads of State, #Political, #General, #United States, #Personal Memoirs, #Hamilton, #Historical, #United States - Politics and Government - 1783-1809, #Biography & Autobiography, #Statesmen, #Biography, #Alexander

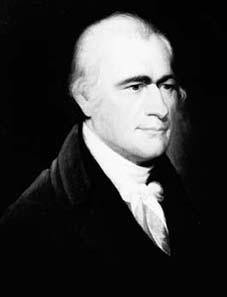

Bottom left:

As vice president in 1802, two years before his fatal “interview” with Hamilton.

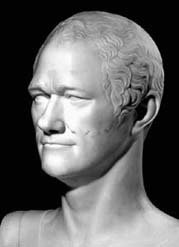

Bottom right:

In 1834, two years before his death, the jaded Burr looked supremely cynical as he sat for his final portrait.

Recently graduated from Columbia, nineteen-year-old Philip Hamilton became embroiled in a sudden dispute over his father’s reputation that resulted in his death in November 1801.

This somber portrait of Hamilton registers profound grief after his son’s death and reflects the sorrows of his last years.

Eliza Hamilton outlived her husband by more than half a century. She was in her nineties when this delicate study was sketched in charcoal and chalk.

Until she died at ninety-seven, Eliza Hamilton doted on this marble bust of her beloved husband by Giuseppe Ceracchi.

Hamilton did not complete the Grange until two years before his death, but his widow and children continued to occupy the pastoral retreat for years afterward.

Political life in the young republic now presented a strange spectacle. The intellectual caliber of the leading figures surpassed that of any future political leadership in American history. On the other hand, their animosity toward one another has seldom been exceeded either. How to explain this mix of elevated thinking and base slander? As mentioned, both sides believed that the future of the country was at stake. By 1792, both political parties saw their opponents as mortal threats to the heritage of the Revolution. But the special mixture of idealism and vituperation also stemmed from the experiences of the founders themselves. These selfless warriors of the Revolution and sages of the Constitutional Convention had been forced to descend from their Olympian heights and adjust to a rougher world of everyday politics, where they cultivated their own interests and tried to capitalize on their former glory. In consequence, the founding fathers all appear to us in two guises: as both sublime and ordinary, selfless and selfish, heroic and humdrum. After the tenuous unity of 1776 and 1787, they had become wildly competitive and sometimes jealous of one another. It is no accident that our most scathing portraits of them come from their own pens.

Far from heeding Washington’s call to desist from attacking Jefferson, Hamilton stepped up his efforts. Increasingly bitter, he was incapable of the forbearance Washington requested. The day before he replied to Washington on September 9, Hamilton found himself reeling from another fresh burst of articles against him. An author named “Aristides”—the name of an Athenian motivated by love of country, not mercenary gain—deified Jefferson as the “decided opponent of aristocracy, monarchy, hereditary succession, a titled order of nobility, and all the other mock-pageantry of kingly government.” He implied that Hamilton had endorsed these abhorrent things when, in fact, he had always condemned them. Noting the anonymous nature of Hamilton’s diatribes, the author likened the treasury secretary to “a cowardly assassin who strikes in the dark and securely wounds because he is unseen.”

72

Freneau’s

National Gazette

continued to lambaste the Federalists as the “monarchical party,” the “monied aristocracy,” and “monocrats”—none of this likely to induce a mood of remorse in Hamilton.

In his September 9 letter, Hamilton applauded Washington’s attempts at reconciliation, then insisted that

he

hadn’t started the feud, that

he

was the injured party, and that

he

was not to blame. He took the feud a step further by recommending that Jefferson be expelled from the cabinet: “I do not hesitate to say that, in my opinion, the period is not remote when the public good will require

substitutes

for the

differing members

of your administration.”

73

As long as it had not undermined the government, Hamilton said, he had tolerated Jefferson’s backstabbing. That was no longer the case: “I cannot doubt, from the evidence that I possess[,] that the

National Gazette

was instituted by him [Jefferson] for political purposes and that one leading object of it has been to render me and all the measures connected with my department as odious as possible.”

74

Hamilton thought it his duty to unmask this antigovernment coterie and “draw aside the veil from the principal actors. To this strong impulse…I have yielded.”

75

In an astounding statement, Hamilton told Washington that he could not desist from newspaper attacks against Jefferson: “I find myself placed in a situation not to be able to

recede for the present.

”

76

Never before had Hamilton refused such a direct request from Washington, and not since quitting the general’s wartime staff had he so willfully asserted his own independence. Even while telling Washington that he would try to abide by any truce, he was preparing his next press tirade. The furious exchanges between Hamilton and Jefferson had hardened into a mutual vendetta that Washington was powerless to stop.

Nor did Jefferson heed Washington’s large-spirited plea for tolerance. In replying to the presidential request, he renewed his withering critique of Hamilton’s system, which, he said, “flowed from principles adverse to liberty and was calculated to undermine and demolish the republic by creating an influence of his department over the members of the legislature.” He charged Hamilton with favoring a king and a House of Lords at the Constitutional Convention—a misconstruction of what Hamilton had said. With greater justice, he grumbled about Hamilton’s unauthorized meetings with British and French ministers, but he also displayed an ugly condescension toward Hamilton that he ordinarily concealed: “I will not suffer my retirement to be clouded by the slanders of a man whose history, from the moment at which history can stoop to notice him, is a tissue of machinations against the liberty of the country which has not only received him and given him bread, but heaped its honors on his head.”

77

The comment smacked of aristocratic disdain for the self-made man. In fact, no immigrant in American history has ever made a larger contribution than Alexander Hamiliton.

Hamilton seemed unhinged by the dispute. In the still secret Reynolds affair, he had shown a lack of private restraint. Now something compulsive and uncontrollable appeared in his public behavior. A captive of his emotions, he revealed an irrepressible need to respond to attacks. Whenever he tried to suppress these emotions, they burst out and overwhelmed him. Throughout that fall, the argumentative treasury secretary donned disguises and published blazing articles behind Roman pen names. Henceforth, he provided a running newspaper commentary on his own administration. Since he saw both his personal honor and the republic’s future at stake, he fought with his full arsenal of verbal weapons. Again and again in his career, Hamilton committed the same political error: he never knew when to stop, and the resulting excesses led him into irremediable indiscretions.

In a new tack, Hamilton carried the battle into enemy territory: the pages of the

National Gazette

itself. Two days after telling Washington that he could not stop his polemics, he appeared twice in Freneau’s paper. As “Civis,” he warned of a Jeffersonian cabal trying to win power at the next election. In “

Fact

No. I,” he corrected the continuing Jeffersonian distortions of his belief that a national debt could be a national blessing. He denied that government debt was a good thing at all times and held that “particular and temporary circumstances might render that advantageous at one time, which at another might be hurtful.”

78

He also charged the Jeffersonians with hypocrisy for opposing both taxes and debt: “A certain description of men are for getting out of debt, yet are against all taxes for raising money to pay it off.”

79

Within a week, Hamilton had returned to his ideological home, Fenno’s

Gazette of the United States,

publishing a new series under the name “Catullus.” He had the cheek to praise himself handsomely, saying that the treasury secretary feared no scrutiny into his motives: “I mistake however the man…if he fears the strictest examination of his political principles and conduct.”

80

As before, Hamilton limned Jefferson as a despot in disguise, masking political ambitions behind republican simplicity. He contended that Jefferson had first opposed the Constitution, then adopted it from expediency. Hamilton didn’t stop with politics and now slashed at Jefferson’s personal reputation. Hinting that he possessed darker knowledge of his subject’s life, Hamilton intimated that Jefferson was a closet libertine: “Mr. Jefferson has hitherto been distinguished as the quiet, modest, retiring philosopher, as the plain simple unambitious republican. He shall not now for the first time be regarded as the intriguing incendiary, the aspiring, turbulent competitor.” “Catullus” said that Jefferson’s true nature had not been exposed before: