Alex's Wake (22 page)

Authors: Martin Goldsmith

“A

LL OF THE

F

RENCH AND FOREIGN PRESS

have been talking for some time now about the lamentable odyssey of Jews who fled Germany and who, on board steamships, have traveled from port to port, never finding the haven that they sought. But now France, perhaps the most hospitable nation in the world, is going to offer them the welcome that so many others have refused. More than two hundred Jewish refugees from the

SS St. Louis

will arrive early tomorrow morning in Boulogne-sur-Mer.”

So read an article in the June 19, 1939, edition of

La Voix du Nord

âthe

Voice of the North

âa regional newspaper serving several cities in northern France. Over the next few days, dispatches from the

Voice

reporter kept readers abreast of what was happening to these weary visitors to their hospitable shores.

At a few minutes past 4:00 a.m. on Tuesday, June 20, in calm seas, the

Rhakotis

pulled into Boulogne's outer harbor at the end of its relatively brief journey from Antwerp. It was a very warm morning and, due in part to the heat, a thick fog arose and blanketed the coast for miles in both directions. Foghorns sounded their booming calls, waking the passengers on board the

Rhakotis

, who were undoubtedly eager to finally set foot on dry land.

Toward 9 a.m., the fog began to lift, the skies cleared, the sun broke through the remaining wisps of mist, and the foghorns ceased their moaning. On board the

Rhakotis

, which was carrying both the French and English contingents of

St. Louis

refugees, small buckets of water were set out to facilitate a morning washing-up for the 224 arriving passengers. At about 10:00, a small shuttle boat, the

France

, left the inner harbor and steamed out to the

Rhakotis

. It was time for those disembarking in France to say farewell to the refugees bound for Southampton. Tears were shed by passengers who had become fast

friends while in exile for more than a month and who now questioned whether they would ever see one another again.

Though outfitted for no more than fifty passengers, the

France

managed to accommodate all 224 refugees. They were greeted by Raymond-Raoul Lambert, the secretary general of the

Comité d'Assistance aux Réfugiés

, who had attended the planning meeting with Morris Troper in Paris five days earlier. Lambert declared grandly, “I welcome you on Free French soil.” The

France

then made its way carefully past the breakwater and into the safety of the Boulogne harbor.

At 10:55 a.m., the

France

tied up at the dock. It was low tide and the boat rode the waves well below the level of the pier, where upward of two hundred people awaited the arrival of their visitors, a crowd made up of journalists, members of the Boulogne Jewish community, curious townspeople, and a few indigents drawn into the unexpected hubbub. As a gangway was attached to the side of the little boat, leading up to the pier, the exiles on board began to cheer and wave hats and handkerchiefs, many of them shouting,

“Vive la France!”

with tears visibly streaking their cheeks.

Three elderly women in their seventies were the first to disembark. They were quickly followed by a stream of young people and their parents, some pushing prams, and a crowd of older men, who formed the majority. Most of the adult passengers wore light-colored raincoats, and all carried a boxed breakfast that the CAR representatives had prepared for them. Each of the sixty children was presented with a bag full of fruits and sweets. “Some of the faces were sad,” reported the press, “but nonetheless the refugees appeared to be in good health and seemed to be in good spirits.”

On the pier, the journalists took photos and exchanged a few words with the newcomers, who were then ushered onto a fleet of waiting buses and driven about a mile to an establishment called the Hotel des Emigrants, at 41 Rue de Liane, where they would rest for several days before moving on to a less temporary address in France. Their luggage would follow, taken off the boat by the longshoremen of Boulogne, who refused payment for their labors. By 11:30, after having been the scene of so much unusual animation, the docks had resumed their normal pace.

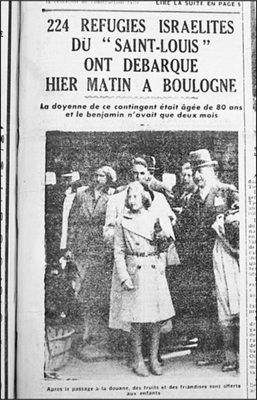

A headline from the June 21, 1939, edition of the

Voice of the North

: “224 Jewish Refugees From the âSt. Louis' Disembarked Yesterday Morning in Boulogne.” The subheadline reads, “The oldest of the group was 80 years old and the youngest only two months.”

At the Hotel des Emigrants, the refugees were greeted by M. Sagnier, a member of the Boulogne Chamber of Commerce, and served a meal of hot coffee, croissants, local cheese, and soup. Everyone began to relax a little, and the reporters from

La Voix

were able to spend some time talking with the weary but happy travelers:

We were introduced to the most senior member of the contingent, an 80-year-old lady who has a son in Cuba. She got a glimpse of him from the deck of the

St. Louis

but was not permitted to go embrace him on land. The youngest refugee was a darling child, barely two months old.

One woman, whose husband already lives in Cuba, wanted to give us her impressions. “Our suffering during this voyage was more emotional than physical. Think of the pain that I suffered

when I learned that I was not permitted to join my husband. The saddest moment of our long crossing was when they refused to let us disembark in Cuba. An epidemic of despair spread rapidly among us and we had to organize a suicide watch and formed an orchestra to cheer up those who were most desperate. I must say that we were well taken care of on board, but you can imagine our joy when we heard that we would be authorized to land at last.” When our conversation ended, we were introduced by the CAR's Gaston Kahn to a charming three-year-old toddler who was in his grandmother's arms and who was unaware that his father, a physician in Berlin, had just died in a German concentration camp.

A reporter from

La Voix

interviewed a young woman from the

St. Louis

, who provided her impressions of the increasingly dangerous quality of daily life within Nazi Germany:

You are unaware of what is going on in my country. Espionage is everywhere. One day I telephoned one of my friends and someone was listening in on our conversation. “Wait,” they said to me, “What is that last sentence you just uttered supposed to mean? This is the Gestapo . . . stay right where you are. We'll be there in fifteen minutes.” In much less than fifteen minutes the agents were in my home. One of them said to me, “You called a certain person. In the future you are forbidden to call her.” The Gestapo is everywhere; you run into their agents in all the streets, you see them in all the buildings. One of my friends' little boy was stopped in the street by a man who asked him, “What did your father say at lunchtime about Mr. Adolf Hitler? What did he say about the regime?” You in free France are unaware of what could happen in your country.

By mid-afternoon, the meal ended, the reporters packed up their notebooks and cameras, and the refugees settled into their rooms at the Hotel des Emigrants. They were permitted to stroll through the hotel's

courtyard to get some fresh air and to use all the establishment's somewhat threadbare facilities, but for forty-eight hours they were not allowed to leave. On Thursday afternoon, however, the doors of the hotel were thrown open and the refugees were given the freedom to stroll wherever they wished through the streets of Boulogne. How wide those boulevards must have seemed to them after their long weeks at sea.

Their liberty lasted through the weekend. On Sunday morning, about thirty children, including the three youngest offspring of Joseph Karliner, left on a bus bound for the Villa Helvitia, a home managed by the

Oeuvre de Secours aux Enfants

(Agency for the Rescue of Children), known as the OSE. Then on Monday morning, June 26, the dispersal of the rest of the French contingent of

St. Louis

passengers took place. The journey began at 7 a.m., when forty-nine people, including Mr. and Mrs. Karliner and their older daughter, Ilse, left for Portiers. Then sixty-five departed for Le Mans, thirty-three for Laval, thirty for Paris, and eighteen, all of them men without spouses, including Alex and Helmut Goldschmidt, for the Professional Re-Education Center in the little village of Martigny-les-Bains in the French district known as the Vosges.

Before they rode away, the refugees expressed their thanks for the hospitality of the authorities, charitable organizations, and the citizens of Boulogne. They also sent telegrams of thanks to French Prime Minister Edouard Daladier and Minister of the Interior Albert Sarraut. Then the motors of the transport buses and autos roared to life and the two hundred souls who had been granted asylum in France, they who had so recently been among the more than nine hundred and had now been further divided, drove up the hill from the harbor and went their separate ways. They had been on French soil for seven days and now they were Wandering Jews once more.

F

RIDAY

, M

AY

20, 2011. In the midst of uncovering these latest events in my grandfather and uncle's odyssey, we are inexplicably interrupted. At noon, we are politely informed that the Bibliothèque Municipale closes for lunch . . . until two o'clock. Eager to continue our research,

I mutter curses under my breath at this Gallic self-indulgence. A two-hour lunch break? On a weekday? As it happens, however, we spend those hours enjoying a delicious

petit déjeuner

of crepes and mineral water at a cozy café across the Place de la Résistance from the library, rambling the ramparts of the old city under a clear blue sky, and finally enjoying a doze, lying in each other's arms in a sunny, sheltered corner of the ancient walls. Not for the last time, I reflect that this continental manner of taking time away from workâby enjoying a long lunch or spending the entire month of August on vacationâis ultimately so much healthier and more civilized than our breathless American pursuit of getting and spending.

We are back in the library promptly at 2:00 and spend the next two hours gathering information from the

Voice of the North

. I emerge with eyes swimming from the effort of focusing on small newsprint and with a heart made heavy by my unresolved sense of failure, my irrational yet very real wish that I'd been here seventy-two springs ago to meet my relatives at the pier and usher them to safety. My mood grows no lighter as we walk back across the square and enter the magnificent Cathedral of Notre Dame just in time to witness the closing moments of a funeral. Six solemn pallbearers hoist the casket to their shoulders and, as they slowly carry the departed to his final resting place, the cathedral is filled with the sound of an organist playing a particularly ornate version of “Auld Lang Syne.” My eyes fill to overflowing.

For the next couple of hours, Amy and I part company. Heading out for a run in Oldenburg a few days ago, she had sustained a foot injury. Armed with a phrase book, she walks off gingerly to buy a new pair of running shoes. I go to search for a trace of the Hotel des Emigrants.

Nine days after D-Day, on June 15, 1944, nearly three hundred planes of the Royal Air Force bombed the inner harbor of Boulogne-sur-Mer to prevent the German navy from using it as a base. The harbor and the segment of the Liane River that flows into the English Channel were completely destroyed. The boulevard running parallel to the river, the Rue de Liane, and the Hotel des Emigrants, at 41 Rue de Liane, were obliterated. Nevertheless, I am determined to stand where Alex and Helmut did when their long oceanic ordeal had ended and they enjoyed

that first meal of hot soup. So, map in hand, I walk south of the harbor along a rebuilt Rue de Liane, looking for number 41.

The

Voice of the North

had mentioned that the hotel was “on the banks of the Liane,” but today there are no buildings on the river side of the rue. On the opposite side of the street, I find a rather soulless apartment building with the number 42. This will have to do, I tell myself, and I take a couple of pictures with my little digital camera to commemorate my visit. But it's a deeply unsatisfying moment. No traces of the hotel remain, nothing for me to touch, to grasp, to embrace. I feel cheated.

Walking with eyes cast down as I cross the Rue de Liane, I incur the wrath of a motorist who has to slam on his brakes to avoid me. I sprawl onto the grass at the river's edge and gaze disconsolately at the current. I am chasing phantoms, I think, and nothing solid remains. Hell, I rage to myself, I don't even have any memories of these people I'm following. I recall our days in Friesland earlier in the week and envy Amy's memories of her grandfather Pete, who told her stories about his childhood journey to Friesland with his father Ysbrand, saying with a straight face that the captain had let him “drive the boat home.” She spent summers with Pete in Iowa, where he raised pigs and chickens on his farm and refurbished feedbags in a workshop overrun with wild rabbits. He fed hobos during the Depression, earning the honor of their mark on his gate identifying him as a generous man. She remembers her grandfather's Zen-like last words to her in his eighty-ninth year: “You like rabbits. You run fast. You'll do OK.”