All Hell Let Loose (65 page)

Read All Hell Let Loose Online

Authors: Max Hastings

But some Germans did not despair, even when they fell into Russian hands. Nikolai Belov cited the example of a prisoner brought in by his reconnaissance platoon, ‘a big fellow of twenty-two. Where do these scoundrels get such youths from? He said that they will launch an offensive in a month, and want to finish the war this year. Germany will of course win.’ Hitler scraped together reinforcements which enabled him by June 1943 to deploy in Russia just over three million German troops. He acknowledged that a general offensive remained impracticable, but insisted on a single massive thrust. His attention focused upon the bulge in the Soviet front west of a monosyllabic place name that would enter the legend of warfare: Kursk. The scale of the eastern conflict is emphasised by the fact that the salient was almost as large as the state of West Virginia, nearly half the size of England. It featured some low hills, many ravines and streams; but most of the region was open steppe – dangerous ground for a tank advance against effective anti-tank fire. Underground iron-ore deposits caused wild compass variations, but this scarcely mattered when neither side had cause for uncertainty concerning the whereabouts of the enemy.

For the Kursk attack, Hitler concentrated much of the combat power of the Wehrmacht, together with three fresh SS panzer divisions, two hundred of his new Tiger tanks and 280 Panthers. Yet the limited scope of

Citadel

, as his operation was codenamed, contrasted with the sweeping offensives of 1941 and 1942, and emphasised Hitler’s diminished means. The Russians readily identified the threat, aided by detailed intelligence provided by their Swiss-based ‘Lucy’ spy ring. At a key Kremlin meeting on 12 April, Stalin’s generals persuaded him to allow the Germans to take the initiative. They were content for the panzers to impale themselves on a defence in depth, before the Red Army counter-attacked. Through spring and early summer, Soviet engineers laboured feverishly to create five successive lines studded with minefields, bunkers and trenches, supported by massive deployments of armour and guns. They massed 3,600 tanks against the attackers’ 2,700; 2,400 aircraft against the Luftwaffe’s 2,000; and 20,000 artillery pieces – twice the German complement. Some 1.3 million Russians faced 900,000 Germans.

Manstein, commanding Army Group South, spent three months assembling his forces, but few Germans other than the Waffen SS formations deluded themselves about

Citadel

’s prospects of success. Lt. Karl-Friederich Brandt wrote wretchedly from Kursk: ‘How fortunate were the men who died in France and Poland. They could still believe in victory.’ Manstein no longer aspired to achieve the Soviet Union’s defeat; he sought only a success which might oblige Stalin to acknowledge stalemate, a strategic outcome that would persuade Moscow to accept a negotiated peace rather than fight to a finish.

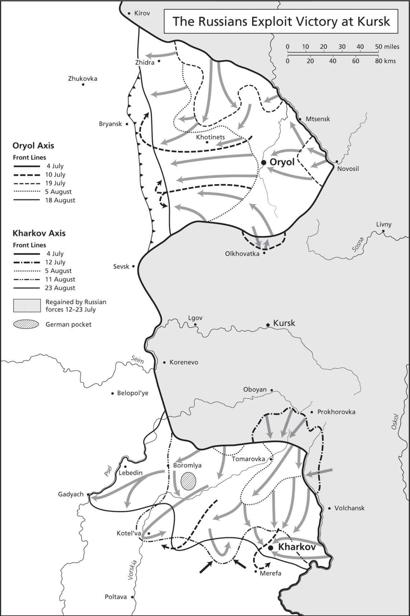

The Russians Exploit Victory at Kursk

Russian soldiers advanced to the defence of Kursk through lands laid waste by their enemies. Eighteen-year-old Yuri Ishpaikin wrote to his parents: ‘So many families have lost their fathers, brothers, the very roofs over their heads. I have only been here a few days, but we have marched far through a devastated country. Everywhere lie unploughed and unsown fields. Only chimneys and stone ruins survive in villages. We saw not a single man or beast. These villages are real deserts now. At night the whole western side of the sky is lit up, copper-red. It makes the soul rejoice to pass an undamaged village. Most houses are empty, but chimney smoke curls from a few, and a woman or boy comes out onto the porch to watch the Red Army pass.’ Ishpaikin, like many others, would never leave the Kursk battlefield.

‘It grew hot as early as 0800 and clouds of dust billowed up,’ wrote Pavel Rotmistrov, commanding a Guards tank army as its long columns moved into the salient. ‘By midday the dust rose in thick clouds, settling in a solid layer on roadside bushes, grainfields, tanks and trucks. The dark red disc of the sun was hardly visible through the grey shroud of dust. Tanks, self-propelled guns and tractors, armoured personnel carriers and trucks were advancing in an unending glow … Soldiers were tortured by thirst and their shirts, wet with sweat, stuck to their bodies. Drivers found the going particularly hard.’ Those who could write penned last letters, while illiterate men dictated to comrades. Twenty-year-old Ivan Panikhidin had survived a serious wound in the 1942 fighting. Now, approaching the front again, he professed pride about taking part in a struggle vital to his country: ‘In a few hours we shall join the fighting,’ he told his father. ‘The concert has already begun, we just need to keep the music going: I write to the accompaniment of the German barrage. Soon we shall attack. The battle is raging in the air and on the ground … Soviet warriors stand firm in their positions.’ Panikhidin was killed a few hours later.

The Luftwaffe battered the Russian lines for days before the assault, achieving a direct hit on the billet of Rokossovsky, who was fortunately absent. German artillery fire was met by a Russian counter-barrage, blasting the ground where formations were massing to advance. On 5 July Model’s forces lunged forward from the north, while in the south Fourth Panzer Army struck. From the outset, each side recognised Kursk as a titanic clash of forces and wills. Stuka dive-bombers and SS Tiger tanks inflicted heavy losses on Russian T-34s. Many of the new German Panthers were halted by breakdowns, but others forged on, crushing Soviet anti-tank guns in their path, while panzergrenadiers grappled with Zhukov’s infantry, using flame-throwers against trenches and bunkers. Both sides’ artillery fired almost without interruption.

After three days, the northern German armies had advanced eighteen miles, and seemed close to breakthrough. Rokossovsky’s army withstood savage assaults, but some of its units broke. A Smersh report denounced officers whom it deemed blameworthy: ‘The 676th Rifle Regiment showed little appetite for combat – its second battalion commanded by Rakitsky left its positions without orders; other battalions also succumbed to panic. The 47th Rifle Regiment’s Lt. Col. Kartashev and the 321st’s Lt. Col. Vokoshenko panicked, lost control, and failed to take necessary steps to restore order. Some senior officers showed themselves cowardly and deserted the battlefield: the 203rd Artillery Regiment’s CO Gatsuk showed no interest in his unit’s operations and with telephonist Galieva retired to the rear areas, where he resorted to drink.’

But others held fast, and Model’s armour suffered massive attrition, especially from Russian minefields. In the south, by 9 July almost half of Fourth Panzer Army’s 916 fighting vehicles were disabled or wrecked. Across the vast battlefield, a jumble of armour and men milled, surged, clashed, recoiled. Flame and smoke filled the horizon. Commanders heard a confusion of German and Russian voices competing in urgency on their radio nets: ‘Forward!’, ‘Orlov, take them from the flank!’, ‘

Schneller!

’, ‘Tkachenko, break through into the rear!’, ‘

Vorwärts!

’. Correspondent Vasily Grossman noted that everything on the battlefield including food became black with dust. At night, exhausted men were unnerved by the sudden descent of silence: the cacophony of the day seemed more acceptable, because more familiar.

On 12 July Zhukov launched his counter-thrust, Operation

Kutuzov

, against the northern Oryol salient. A German tank officer wrote: ‘We had been warned to expect resistance from PaK [anti-tank guns] and some tanks in static positions … In fact we found ourselves taking on a seemingly inexhaustible mass of enemy armour – never have I had such an overwhelming impression of Russian power and mass as on that day. The clouds of dust made it difficult to get support from the Luftwaffe and soon many of the T-34s had broken through our screen and were scurrying like rats across the battlefield.’ In the mêlée of armour, some tanks of the rival armies collided, halting in a tangle of tortured steel; there were many exchanges of fire at point-blank range. Across hundreds of miles of dusty plain and blackened wreckage, the largest armoured forces the world had ever seen lunged at each other, twisting and swerving. Turret traverse was often a lethal race, in which survival was determined by whether a Russian or German tank gun fired the first round. By nightfall on 12 July, rain was falling; the two armies embarked on the usual struggle against the clock, exploiting darkness to recover disabled tanks, evacuate wounded and bring forward fuel and ammunition.

The important reality was that German losses were unsustainable: Manstein’s assault had exhausted its momentum. Even where the Russians were not advancing, they held their ground. That same day 2,000 miles away, the six US and British divisions that had landed in Sicily began to sweep across the island. Hitler’s nerve broke. On 13 July, he told his generals he must divert two SS panzer divisions, his most powerful formations, to strengthen the defence of Italy. He aborted

Citadel

. Zhukov surveyed the battlefield with Rotmistrov. The tank general wrote: ‘It was an awesome scene, with battered and burned-out tanks, wrecked guns, armoured personnel carriers and trucks, heaps of artillery rounds and pieces of track lying everywhere. Not a single blade of grass was left standing on the darkened soil.’ The Germans kept attacking for a few days more, in hopes of salvaging something that Berlin might claim as a victory, but they were soon obliged to desist. Manstein’s reputation for invincibility was among the casualties of Kursk, though he never accepted responsibility for failure.

Behind the front, partisans staged fierce attacks on German communications, executing 430 rail demolitions on 20–21 July alone. Hapless train crews, Russians conscripted by the occupiers, were summarily shot when they fell into guerrilla hands. By mid-1943 the Russians claimed to deploy 250,000 partisans in Ukrainian and other eastern wildernesses beyond German control. Their guerrilla activity made far more impact than that of any western European resistance movement, aided by Moscow’s indifference to Wehrmacht reprisals against the civilian population. ‘The Germans sent tanks, aviation and artillery against this partisan region,’ wrote a Russian correspondent when he visited a liberated area, ‘and they crushed it. Every village has been reduced to ashes. Their inhabitants fled into the forest … Partisan detachments dispersed, because it was impossible for big groups to survive. They are unable either to hide (the Germans keep combing the woods) or to support themselves. Food is very scarce. Sivolobov’s detachment has lived exclusively off the meat of slaughtered cows and horses for two months. They couldn’t stand the sight of meat any more. There was no bread, no potatoes, nothing … Civilians are better off. They have managed to tuck some food away, for instance burying stuff in fake graves. The enemy realised that something was going on, but when they started digging one up, they found only a dead German! The terror is awful. In some places they are shooting boys no older than ten as “Bolshevik spies”.’

Model’s army maintained a tigerish defence in the Kursk salient until 25 July, then started to fall back. On 5 August, the Germans lost Oryol and Belgorod. On the 25th the Russians regained Kharkov – and this time kept it. Soldier Alexander Slesarev wrote to his father: ‘We’re crossing liberated territory, land that has been occupied by the Germans for two years. People emerge joyfully to greet us, bringing apples, pears, tomatoes, cucumbers and so on. In the past, I knew Ukraine only from books, now I can see with my own eyes its natural beauties and many gardens.’ The resumption of Soviet rule was not an unmixed blessing for Stalin’s people. ‘It is a shame, when you travel around liberated villages, to see the cold attitude of the population,’ wrote a soldier. The Germans had permitted peasants to sow and harvest their own plots; the returning Soviets reimposed rigorous collectivisation, which provoked some protest riots recorded by Lazar Brontman. Every tractor and almost every horse was gone, so that land could be tilled only with spades and rakes, sometimes by women pulling ploughs. Even sickles were seldom available.

Local communities struggling for subsistence displayed bitter, sometimes savage hostility to refugees who passed by – in their eyes, such people were locusts. A peasant woman wrote from Kursk province: ‘It’s hard now that we don’t have cows. They took them from us two months ago … We’re ready to eat each other … There isn’t a single young man at home now that they’re fighting at the front.’ Another woman wrote to her soldier son, lamenting that she was reduced to living in the corridor outside her sister’s one-room flat. Yet another told her soldier husband: ‘We have not had bread for two months now. It’s already time for Lidiya to go to school, but we don’t have a coat for her, or anything to put on her feet. I think Lidiya and I will die of hunger in the end. We haven’t got anything … Misha, even if you stay alive, we won’t be here.’ In the village of Baranovka, which had been occupied by the Germans for seven months, Lazar Brontman found only a few farm buildings still standing. The former manager of the local collective farm was living in a cowshed with his wife and three small daughters. Their stomachs were distended by starvation.