Amazing Tales for Making Men Out of Boys (2 page)

Read Amazing Tales for Making Men Out of Boys Online

Authors: Neil Oliver

Kathleen Bruce was 29 years old and had her heart set on a career as a sculptor when she attended a lunch party in an elegant house in London’s Westminster Palace Gardens in 1907. Given how eager she was to establish herself among the capital’s creative and artistic types, she must have been pleased to note, as she walked into the dining room, that her fellow guests included the playwright J. M. Barrie, the novelist Henry James and the esteemed theater critic Max Beerbohm.

The youngest of a family of 11, she had lost both her parents before her 16th birthday. She’d been taken in then by her granduncle, William Forbes Skene, historiographer of Scotland, and there in his Edinburgh home she had grown into a woman of the sort de scribed, in those far-off days, as being “of independent spirit.” Later she enrolled at London’s Slade School of Art, and by the age of 21 she was in Paris, studying at the Académie Colarossi and every inch the art student. She knew Auguste Rodin, and it was while working for him in his studio that she met and made friends with the American dancer Isadora Duncan. She had lived and worked in Florence as well, and by the time of the lunch party in London she had been back in England for just a year.

It certainly was a glamorous gathering. She was introduced to the

young would-be actor Ernest Thesiger, a grandson of the 1st Baron Chelmsford and a relative of the late Lieutenant General Frederic Thesiger, 2nd Baron Chelmsford and commander of the British forces during the Anglo-Zulu War of 1879. It was while making polite conversation with the younger Thesiger that she noticed, seated between Mr. Barrie and Mr. Beerbohm, “a simple and austere naval officer.”

Ernest was being quite persistent, however, and after the briefest of glances at the other man, who seemed somehow out of place in such company, she resumed the business of being charmed. Ernest had been enrolled at the Slade and had had early ambitions of being a painter. He had quickly switched his attention to drama, though, and in 1907 was just two years away from the debut of a long and successful acting career.

Then, as Kathleen later noted in her diary, “all of a sudden and I did not know how,” she found herself face to face with the uniformed man. As he introduced himself she saw that he was of medium height, with broad shoulders, slim waist and thinning hair. “He was not very young,” she wrote, “perhaps 40, not very good-looking but healthy and alert.” More promisingly, he had “a rare smile and…eyes of a quite unusually dark blue, almost purple. I had never seen their like.”

Kathleen Bruce’s scrutiny of this middle-aged man was anything but casual. As well as making her name as a sculptor, she had another quite different creative ambition. Now, as she approached her 30th birthday, still without a husband, it was always at the back of her mind. While still in Paris she had told at least one girlfriend she was determined to have a son.

“A son,” she said, “is the only thing I do quite surely and always want.”

Kathleen was not a beautiful woman—handsome would be nearer the mark. In photographs her features are certainly clearly

defined and strong. There’s a prominent nose and chin. Her dark hair is long and uncut. How do women describe that Edwardian style of piling hair into a roll on the back of the head…a chignon, maybe? Her eyes were blue and set off by the only piece of jewelry she liked to wear—a pendant made from a single blue stone.

Anything she lacked in the looks department, though, she made up for in charm and presence. She certainly wasn’t without male admirers. But when her girlfriends bothered to point out that she should have no difficulty in getting what she wanted, Kathleen replied that no one she had met so far was worthy of being the father of her son. The way she spoke about the business of breeding made the whole thing sound more like a mission—a destiny perhaps—than any mere desire.

As Kathleen looked into the near-purple eyes of this naval officer, she began all at once to wonder if she was meeting the gaze of her Mr. Right, “the father of my son for whom I had been searching.” She wasn’t certain—and seemed rather to be asking herself the question in an air of mild disbelief. “Is this

really

him?”

What Kathleen either didn’t know at that moment—or hadn’t admitted to herself—was that she was looking for a hero, a manly man. Heroes are hard to find, and step out into the daylight when they are needed rather than when they are sought.

Heroes and manly men don’t conform to a look or a style and they have come from all classes and every race. They are a rare breed and, most inconvenient of all, they don’t know they

are

heroes and so cannot identify, far less introduce themselves as such. Like beauty, heroism is in the eye of the beholder. It is up to us lesser mortals to spot our heroes, and they are to be found in the strangest places, even lunch parties in southwest London.

The man Kathleen Bruce was talking to quite awkwardly in the dining room of the house at 32 Westminster Palace Gardens was

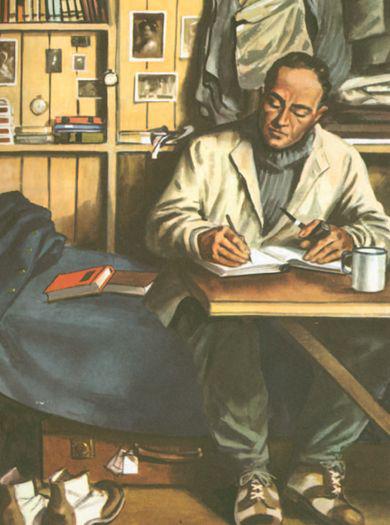

Captain Robert Falcon Scott—Scott of the Antarctic. She had recognized him, of course—he had already made his name as an Antarctic explorer, and in an age when military men and explorers were among the A-list “stars,” this naval captain was shining brightly.

But was he a hero, or even a manly man?

He

didn’t think so, not always at any rate. In fact, from the age of 20 he had been confessing to his diary what he saw as his shortcomings as a man, far less a manly man.

He didn’t even look the part. Average height, average build, no oil painting as far as his looks went—losing his hair by his middle years and definitely balding well before the end. When he was a young boy his family considered him to be on the soft side—frail and delicate, with a weak chest and a tendency to be knocked down by any passing chill or virus. Like Oscar Wilde, it seems, he was susceptible to draughts. He was also absentminded, shy and apt to become squeamish at the sight of blood or the suffering of animals. He may have inherited his delicate constitution from his father, John. John Scott certainly never went to sea. When Grandfather Robert Scott retired, he went into the brewery business with his brother Edward. Young John was kept safe at home, to train as a brewer.

A Navy doctor who examined Scott before he joined the service reported that he didn’t have a robust enough physique. A later biographer described him as “shy and diffident, small and weakly for his age, lethargic, backward and above all, dreamy.”

Some of his early diary entries suggest he suffered from the great blight that is mild depression, or just good old-fashioned existential angst: “this slow sickness which holds one for weeks,” he wrote, “how can I bear it? I write of the future, of hopes of being more worthy, but shall I ever be? Can I alone, poor weak wretch that I am, bear up against it all? How can I fight against it all? No one

will ever see these words, therefore I may freely write: What does it all mean?”

Poor weak wretch!

This is marvelous stuff for us! These are the innermost thoughts and words of the young man destined to be Captain Scott of the Antarctic! This means you don’t have to be born manly and heroic. You can start out weak and feeble and progress to manliness by sheer force of will! And all that introspection and self-doubt confessed to the pages of a diary: there’s hope for us all.

Scott was born on June 6, 1868, in the family home, a place called Outlands just outside Devonport. In all, there would be six children for churchwarden John Scott and his wife, Hannah—including Grace (known as Monsie), Rose, Robert, Kitty, Ettie and Archie. He was probably named Robert after his paternal grandfather, a Navy man who had reached the rank of purser by the time he retired. Family legend had it that they were all descended from one John Scott—a Jacobite sea captain who’d been captured and hanged for his part in the ’45 Rebellion (another great story—another layer of glamour and intrigue). His middle name, Falcon, was the surname of his godparents, and his family and close friends always knew him, not as Robert, but as “Con.”

In the quest for manliness, it doesn’t hurt to have a cool name like Con, especially when it’s short for Falcon. Names matter, and can set a young man off toward a manly destiny right from the word go. I went to school with a boy called—and I’m not making this up—Steel. Imagine growing up with a name like Steel. You couldn’t help but be straight-backed with a firm handshake and confident gaze if your mom and dad had decided to name you after something hard, sharp and shiny! My niece went to nursery school alongside a boy called Luke Walker. Nothing unusual or obviously cool in that, you might say. Little Luke’s middle name, however, was Skye—spelled like the island off Scotland’s northwest

coast. So, Luke Skye Walker—a boy could go far with a name like that.

All three of grandfather Robert Scott’s brothers went to sea as well, so it was an obvious career path for young Con, in spite of the reservations of the doctor. The historic port of Plymouth was just up the road from the family home—further inspiration for a life before the mast—and after a few years of being coached for a Navy cadetship, he boarded the training ship

Britannia

at age 13. He took his exams in 1883 at just 15, and was subsequently rated as a midshipman.

It’s impossible to know what means Con Scott used to transform himself from a sickly little boy into a young man capable of putting up with, even thriving within, the unremittingly harsh world of Her Majesty’s Royal Navy. For boys like Scott the training was little changed from that dished out in the days of Admiral Nelson, with severe discipline enforced by beatings and extra drills. Regardless of the weather they would be sent up the rigging, to heights of 120 feet or more, to literally “learn the ropes” while the deck rolled beneath them and their perches swung sickeningly. They slept in hammocks slung close together below decks and there was neither acknowledgment of, nor sympathy for, any of the natural feelings of homesickness, fear or lack of confidence. Where did Scott find the emotional and physical strength to cope with it all? Who did he model himself upon? Whose example did he try to follow?

Was he inspired by the thought of that shadowy Jacobite ancestor, perhaps? Or had he read and been told about the lives of other manly men?

Growing up close to Plymouth he would have known by heart the stories of the great seamen who’d sailed from there into their places in history. Sir Francis Drake set out to tackle and defeat the Spanish Armada; Sir Walter Raleigh departed for Guinea; and, in

1576, Sir Martin Frobisher set sail with the

Gabriel

and the

Michael

in search of the fabled North West Passage to Cathay.

In Robert Falcon Scott’s day all young boys knew the lore of the heroes. In order to become manly men, they needed to know how manly men behaved—how they carried themselves, how they lived their lives and, when necessary, died their deaths.

The world he’d been born into in 1868 was one unrecognizable to us. It was a place so different from the one we know—in terms of our values and morals at least—that it’s as distant as the imagined world of Homer.

The American Civil War had ended just three years before. The Crimean War of 1854–56 was only a dozen years distant. Legendary conflicts like the British invasion of Afghanistan in 1838 (and the disastrous retreat from Kabul that ended it in 1842) and the Indian Mutiny of 1857–59 were still well within living memory when Con was a boy. Such stories! Such lessons to be learned!

Rudyard Kipling was born in 1865, in Bombay. At the age of five he was sent to live with a foster family in Southsea, back in wet and draughty England. He was desperately unhappy. But Kipling would of course grow up to deliver many of the lines that helped shape the attitudes and aspirations of generations of manly men:

If you can make one heap of all your winnings

And risk it on one turn of pitch-and-toss

And lose, and start again at your beginnings

And never breathe a word about your loss

If you can force your heart and nerve and sinew

To serve your turn long after they are gone

And so hold on when there is nothing in you

Except the Will which says to them: “Hold on!”

So this is not about wanting to fight or to kill or to die, far from it—it’s about wanting to value an upright and noble way of living. It’s not about conquering or wanting to build empires, either. Men like Kipling, Raleigh and Frobisher and dramas like Afghanistan and the Crimean War and the rest have other things to say; they tell us that there are bigger stories to be told, and parts for us to play in them. One of the lessons to be learned from the old stories was that being a man meant there were more important things to think and care about than your own wellbeing.

When boys like Con Scott realized this—boys with weak chests and nervous hearts, who felt faint at the thought of suffering or at the sight of blood—it must have brought feelings of release and relief. It was possible to change, to become more than they had been before!

What is also true, of course, is that there are still brave men. It’s not as though they’ve stopped turning up when need arises, far from it. It just feels sometimes that we’ve stopped paying them the attention they used to get—the attention they deserve.

In his own time and after, Scott would cast a long shadow against which young men would measure themselves. But examples are still being set, shadows cast, and the bravery of good men is as constant as the sea.