American Eve (51 page)

Authors: Paula Uruburu

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Historical, #Women

There was even the occasional rumor that she was getting back together with Harry Thaw, who came to see her several times in nightclubs in Atlantic City, Manhattan, and Chicago (this after he was released from the Kirkbride Asylum in Philadelphia, after nearly eight years of institutionalization for the “Frederick Gump debacle”). But money that Harry promised to give her “for her son” never materialized (although he did buy Russell a bicycle one Christmas). As time passed, by his twenties, Russell, having inherited his mother’s devil-may-care attitude in his approach to life, became a well-known and daring test pilot whose acquaintances included Charles Lindbergh and Amelia Earhart. Sadly, it was around this same time that Evelyn’s unfortunate brother, Howard, from whom she had remained estranged and who always seemed to exist on the periphery of life, succeeded where Evelyn had failed. He hanged himself.

A devastated Evelyn struggled as a single mother in the Depression and the war years, during which time her mamma died. She made varied and valiant attempts to regain control of her life between the late twenties and 1945. She “sobered up” on a milk farm, ran her own Club Evelyn Nesbit in Atlantic City, opened a tearoom on Fifty-seventh Sreet in Manhattan, and started a line of cosmetics—all of which eventually failed. Gradually, the nightclubs and cabarets she performed in, doing songs like “I’m a Broad-minded Broad from Broadway” and “I’m No Man’s Woman Now,” were seedier and farther away (as far as Panama City) from the fickle and unforgiving limelight. A serialized account of her life in the New York

Daily News

was part of the inspiration for Orson Welles’s depiction of the pitiable has-been alcoholic singer in

Citizen Kane

, which many believe is based on Marion Davies. When Harry Thaw died of a heart attack in 1947, he left Evelyn $10,000, the same amount he left a waitress he barely knew who worked in a coffee shop in Virginia. Then, just as she had immediately after the murder that fateful night in Madison Square Garden, Evelyn Nesbit seemed to vanish from the scene. Far from the prying eyes of a capriciously curious and unsympathetic public, Evelyn moved to southern California to live with her son, Russell, and his wife and family, which eventually included three grandchildren.

A little more than two decades after the Madison Square Tragedy, F. Scott Fitzgerald had proclaimed, “There are no second acts in America.” But he was wrong.

In 1954, in true Hollywood fashion, Evelyn Nesbit emerged from the shrouded depths of insignificance and infamy when she sold her story to Twentieth Century-Fox. Hired as a consultant for the film,

The Girl in the Red Velvet Swing,

with a twenty-one-year-old Joan Collins in the title role, Evelyn basked once again, however briefly, in the twilight of kinder and nostalgia-inspired publicity. After a decade-long career as a sculptor and ceramics teacher, Evelyn ended her days confined to a wheelchair and then a bed in a series of convalescent homes. Nevertheless, her mind remained sharp and vibrant as she kept contact with the outside world through hundreds of letters written to several friends. She died in 1967 “of natural causes.”

FINALE

In those hypocritical years when the scandal she ignited simultaneously shocked and titillated the public, Evelyn attempted to wear her notoriety with tenuous, shrinking dignity, though she barely succeeded in keeping her head above water. And although in some ways she remained hopelessly naive and childlike until her last days, she was, however, shrewd enough not to reveal “the whole truth” about her story while she lived. Perhaps this enabled her to negate her past and any guilt she may have felt about the murder of Stanford White, the only man she said she ever truly loved. Perhaps she came to realize that the only control she would ever have over her life was how much or how little of it to disclose, telling the truth, but (as Emily Dickinson might say) telling it slant (“success in circuit lies”).

She resented being considered merely a cultural oddity “like something in Barnum’s museum,” but the questionable publicity she was routinely engaged in did ultimately provide a living for herself and her son, whose paternity Harry Thaw denied to his dying day. She had, according to all those who knew her personally in her later years, “great presence and an assured manner and she could never, never become an obscure housewife. ” Into her eighties Evelyn was, as described by her daughter-in-law, “a free spirit,” even though she was forever bound up in the mythology surrounding the “girl in the red velvet swing.” Her name now resides in that realm where fact has fused with fiction.

Florence Evelyn Nesbit lived more than most in the first twenty-one years of her early turbulent life and then spent the next sixty contending with the myth she had become and helped invent. And reinvent when the occasion presented itself. Yet even at eighty-two, one could see the spirit of the young model come to life when someone produced a camera; she instinctively struck the characteristic pose that made her famous— her head tilted slightly back and to the side, her eyes seductively half-closed, an enigmatic smile on her face.

American Eve.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

There are so many people over the course of a decade who helped me with this book that I am sure to forget to thank someone; I apologize in advance.

I want to thank Greenpoint, Brooklyn, for my parents, Martin and Estelle. I’m indebted to my mom and thank my sister, Pam, for her unwavering faith in me, and although I miss my dad, who offered his keen endorsement at the start of my book, I am very happy to have Michael Martin, my nephew, born halfway through this process, who seems at uncanny moments to channel my father’s spirit. I want to thank the Winks of Seaford Manor for their continued encouragement, and the Pittsburgh branch, who offered a base of operations for my research in what seems a lifetime ago. Then there are my own “kids,” who not only understand my madness but share it—Tammy Baiko, Eric Chiarulli, Nick Mougis, Allyson Smith, and Brian Smyth. And of course, none of this would have mattered as much were it not for Lisa Cardyn and Lorri Ford, whose friendship and perseverance in the face of seemingly insurmountable odds are a constant source of inspiration.

This book would not have been as meaningful and vivid were it not for Russell Thaw, Evelyn Nesbit’s wonderfully supportive grandson, and his mother, Barbara Thaw; their generosity and assistance with this project from its inception made me fearless in the face of a hundred years of mythology. I also would not have been able to complete this book were it not for continued institutional support from Hofstra University, its Faculty Research and Development Grants, and leave time. As for creative minds and kind hearts, I am particularly grateful to Paul Baker, Kevin Brownlow, Carl Charlson, Stuart Desmond, Ed and Helen Doctorow, Adolph Grude, George Hatie, Suzannah Lessard, Joe McMaster, Jay Maeder, Jim Petersen, and Ira Resnick. Their assorted acts of benevolence, encouragement, and advice have helped me greatly.

I am of course extremely grateful to my agent, Katharine Cluverius, at ICM, my editor, Sarah McGrath, whose instincts are right on, and her assistant, Sarah Stein, at Riverhead Books; each has helped me immeasurably to make this dream a reality, and I wish Katharine and Sarah M. the best world possible for their own new additions.

There is no way I can qualify the unconditional emotional support and intelligent contributions (editorial and otherwise) made by my friends and colleagues throughout this process (listed here in alphabetical order), so I will simply say thanks to Iska Alter, Dana Brand, Joe Fichtelberg, Bernie Firestone, Brad Hodges, Gloria Hoovert, John Klause, Susan Lorsch, Meghan Molloy, Jean Ng, Karen Schnitzspahn, and Chris Svatba. There have been many times when, immersed in my research or my writing, I have felt like Dorothy stuck in Oz, maddeningly unaware how close I was to home all the time, and I could never have made this strange journey without the brains, courage, and heart of Chris Rubeo, Allan David Dart, and Russell Svatba.

Last,

American Eve

is dedicated to my captain, the person who taught me the exaltation of an inland soul, Brian Molloy. His resolute spirit, fierce intellect, and joyous sense of humor made this all possible, and I miss him most of all.

NOTES

I began working on

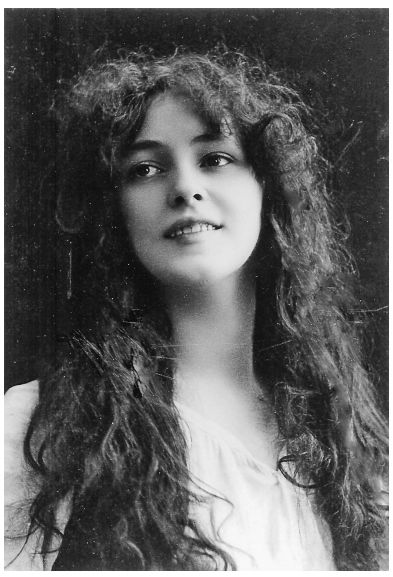

American Eve

more than ten years ago as an accidental tourist in somewhat unfamiliar territory. While doing research for a course I teach called “Daughter of Decadence,” I looked for iconic images of women that would reflect the period in which the images were produced. In an unGoogled, pre-eBay world, I extended my search beyond the usual libraries and archives into the realm of antiquarian books and postcards, private collectors, and “ephemera” shows. At my very first postcard show I was intrigued by a category labeled Pretty Ladies (sandwiched, symbolically, between Perambulators and Prisons). While thumbing through hundreds of postcards I was suddenly struck by one in particular. The sultry gaze of a young girl poised dreamily in turn-of-the-century fashion seemed almost hypnotic. At the bottom it read “The Debutante—posed by Evelyn Nesbit.” Her name was not unfamiliar to me. I had read E. L. Doctorow’s wonderfully evocative novel

Ragtime

and seen the 1981 film adaptation based on the book; in both she is a featured character. As weeks, then months passed, the face or name of Evelyn Nesbit emerged with astonishing regularity.

I soon became obsessed with uncovering the facts buried beneath the fictions that had been written about this astonishing-looking young woman and the events surrounding the night that sealed her fate as “the girl in the red velvet swing.”

When I began this book, no one had written anything that attempted to distinguish objective fact from subjective fancy or that tried to put Evelyn Nesbit’s fascinating and fractured life into the broader cultural context of her “gilded cage” (and certainly not from a woman’s perspective). I saw this, then, as my task, and soon discovered that Evelyn Nesbit told and retold several versions of the crucial events that shaped her life, first on the witness stand in 1907, again in

The Story of My Life

(written as Evelyn Thaw in 1914), and then in a second memoir,

Prodigal Days

(written as Evelyn Nesbit in 1934, and published in the UK as

The Untold Story

). In spite of sometimes frustratingly variant autobiographical versions of her story, I now had significant pieces of information as well as self-generated mythology that I could begin to sift through and a historical timeline I could piece together to form a cohesive narrative. As I discovered, Harry Thaw also wrote a bizarre version of the events leading up to his murder of Stanford White in his own book,

The Traitor

(published, appropriately, by a vanity press in 1925), which in its own strange way also helped me stitch together a fuller story.

The New-York Historical Society, the New York Public Library, the Museum of the City of New York, the Madison Square Park Conservancy, the Lincoln Center Theater Collection, the Smithsonian Institution, the Archives of American Art, and the Library of Congress have all been extremely valuable in providing materials that have helped me tie together the “threads of destiny” that hold this book together. It was also my good fortune to have had the support of Evelyn’s family (particularly her grandson, Russell Thaw), who gave me full and unprecedented access to personal family archives, including letters and photos. In addition, I am beholden to the private collections of Ira Resnick, George Hatie, Adolph Grude, Lisa Cardyn, and Lorri Ford, as well as Kevin Brownlow and Photoplay Productions, Inc. The list of works that have been invaluable as source materials are listed under “Further Reading.”

Just as I have tried to keep my citations as concise as possible, citing directly quoted material and omitting only those citations related to facts that are widely known and accepted (as well as quotations taken from periodicals and newspapers of the period for which I had clippings or parts of clippings but no other identifying source), I have also tried to let Evelyn speak for herself as much as possible, since her voice is the one that has been the most muffled and misinterpreted over the last hundred years in spite of her best (or worst) efforts. I therefore apologize if at times my relating of her recollections leads to some factual errors or seeming inconsistencies, particularly regarding her early life. Unless noted, her quotations are taken from

The Story of My Life, Prodigal Days, The Untold Story,

and unpublished letters in private collections and interviews with family members. Unless otherwise noted, Harry Thaw’s quotations are taken from his book,

The Traitor.