American Gun: A History of the U.S. In Ten Firearms (33 page)

Read American Gun: A History of the U.S. In Ten Firearms Online

Authors: Chris Kyle,William Doyle

Tags: #History, #Non-Fiction

One of the interesting things about the AR15 is its size. Next to the rifle we started this book with, the American long rifle, the modern AR15 combat rifle is small. There’s an advantage in that: it can also be handled by a wide range of people.

Back when our friend Sergeant Murphy was shooting officers out of their saddles, the Continental Army and the American militias were almost exclusively male. Now women are an important part of the military and law enforcement forces.

And so maybe it’s appropriate we end this little tour of the modern combat rifle with the story of Leigh Ann Hester

In civilian life, Leigh Ann Hester was a petite, twenty-three-year-old woman who helped manage a shoe store in Nashville, Tennessee. At 9 a.m. on Sunday, March 20, 2005, she was a U.S. Army sergeant with the 617th Military Police Company, Kentucky National Guard stationed in a combat zone in Iraq. She and her squad of eight men and another woman were patrolling a road south of Baghdad and just north of Salman Pak. As usual, she had her short-barreled M4 within easy reach inside her up-armored Humvee.

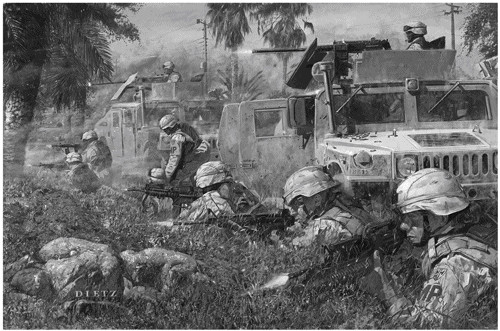

Artist James Deitz’s depiction of the events of March 20, 2005, in Salman Pak, Iraq. Sgt. Leigh Ann Hester—and her M4—is pictured in the foreground at bottom right.

U.S. National Guard (painting by James Deitz)

Suddenly, Hester heard gunshots and explosions ahead. The patrol sped up, reaching a convoy of thirty civilian supply trucks and tractor-trailers. The vehicles were being ambushed with intense small-arms fire from the side of the road. An unusually large force of insurgents had filled trenches along the highway and were firing at the trucks. Bullets were flying everywhere.

Staff Sergeant Timothy Nein, in the lead Humvee, saw the civilian trucks trying to scatter. “Flank ’em down the road!” hollered Nein to the rest of the squad. A moment later, a rocket-propelled grenade slammed into the top of his vehicle. Waves of rifle fire punched into the grill and side door as the Hummer ground to a halt.

The others stopped and began engaging the insurgents. The Humvees took multiple hits. In the third truck, all the soldiers except Specialist Jason Mike were wounded. Mike grabbed an M4 assault rifle and an M249 light machine gun and began firing in two different directions to push back the attackers.

Hester spotted a convoy of seven parked cars not far away. The enemy was planning a fast getaway—and more than likely a kidnapping as well. Nein, who was still fighting despite the hits his vehicle had taken, decided their best bet was to go on the offense. He took his rifle and started walking directly toward the enemy positions in the trenches and behind trees and piles of dirt.

Hester jumped from her Humvee to back him up. Carrying her M4 and attached grenade launcher, she ran up alongside Nein as he took cover behind a berm. Nein plugged an insurgent as he popped his head out from behind a tree. Hester zeroed in on a man with a machine gun. She put him in her sights and squeezed the trigger.

“It’s not like you see in the movies,” she said later on. “They don’t get shot and get blown back five feet. They just take a round and they collapse.”

Hester gunned down another insurgent, then she and Sergeant Nein jumped into a nearby drainage ditch to get a better angle on the enemy. They started working their way down, pushing the insurgents back, step by step, using rifle fire and a grenade from Hester’s launcher. When they started running low on ammo, Hester ran on back to her Humvee to get more. The firefight went on for more than thirty minutes until other U.S. forces arrived. The wounded were evacuated by helicopter, and the area was eventually secured. The Americans killed twenty-seven insurgents, wounded six, and took one prisoner. Hester personally killed at least three Iraqis with rifle and grenade fire from her M4. She received the first Silver Star given to a woman since World War II. Six other soldiers in her unit were decorated, including Specialist Jason Mike, Sergeant Timothy Nein, and Specialist Ashley Pullen.

Sergeant Hester “maneuvered her team through the kill zone into a flanking position where she assaulted a trench line with grenades and M203 rounds,” according to the Army citation that accompanied her Silver Star. “She then cleared two trenches with her squad leader where she engaged and eliminated three AIF [anti-Iraqi forces] with her M4 rifle. Her actions saved the lives of numerous convoy members.”

“It was either me or them, and I wasn’t going to choose the latter,” she said. “Adrenaline was pumping, bullets were flying, and I didn’t have a choice but fight back.

“I think about March 20 at least a couple times a day, every day, and I probably will for the rest of my life,” admitted Hester. “It’s taken its toll. Every night I’m lucky if I don’t see the picture of it in my mind before I go to sleep, and then even if I don’t, I’m dreaming about what we did.”

Leigh Ann Hester says she doesn’t feel like a hero. “I did my job.”

Amen to that.

Pick up a rifle, a pistol, a shotgun, and you’re handling a piece of American history. What you hold is not just a finely engineered instrument, but an object that connects you to people who fought for their freedom in the backwoods of Saratoga, New York, died on the rolling hills of Gettysburg, and cornered criminals in the canyons of big cities across the country. Each gun has its own story to tell, its own connection not just to the past, but the American spirit.

Guns are a product of their time. An American long rifle, stock smooth and silky, frame lightweight, barrel long and sleek—the man who made this gun worked in the dim light of a small forge, and chose carefully the wood to use. His fingers went raw as he honed the stock, and the iron from a nearby mine stained his hands and the water he used to cool the parts as he finished.

Take the gun up now, and the smell of black powder and saltpeter sting the air. Raise the rifle to your shoulder and look into the distance. You see not a target but a whole continent of potential, of great things to come, a promising future . . . but also toil, trial, and hardship. The firearm in your hands is a tool to help you through it.

A Spencer—now here is an intricate machine, a clockwork of a gun finely thought out, each piece doing many different parts of the job as the weapon is aimed and gotten ready to fire. This is a gun of a time when imagination sprang forward, when the brain was a storm of ideas, one leading to another, then more, and others beyond that. This is a machine of pieces in a complicated dance, made to work as one; a machine no stronger than its weakest part. It is a sum far more than the simple addition of stamped metal bits and honed edges. The Spencer and its contemporaries come from a time not just of cleverness, or the birth of great industry. All of those, yes, but the weapons were also born in a time of disruption, of fear, of our better selves wrestling with weakness and temptation. Would we be one nation? Would we be several? What future would we have?

Preserving the Union was just one job the Spencer and the other repeaters, revolvers, and early machine guns were invented to solve. They had other, even bigger questions to help us answer: Would we conquer nature, or be conquered by it? If we could tame the wild, could we tame ourselves? Would we overcome our worst impulses and make a better America, then take a leading place in the world?

And once there, what of it?

The answers were positive, on the whole. But they were not given without great struggle and missteps. There were terrible detours: injustices, unnecessary violence, and criminals who found a way to use for evil what should have been, what were, instruments of progress.

In the end, those same tools helped us endure. They faced down the worst evil of our times. They stopped genocide and the enslavement of a people. The Thompson submachine gun didn’t just redeem its own reputation fighting evil in World War II; it helped all of us redeem man’s potential. After the darkest shadows spread over Europe and Asia, after insanity pushed away common sense and decency, we were able to recover. Weapons did not do it; guns were just helpers, tools as they always are. Men and women did it. But the tools that men and women made, that they carried in their arms and slung on their backs, were a necessary and important part of the struggle.

A gun today is a wonder of high-tech plastic, metal, and compounds too long and complicated to pronounce. Building on the past, gun makers have skimmed away every excess possible, until their products weigh no more than necessary for the job at hand. They pack into a tiny chamber the power of jet engines and rocket ships. They split the world into minute fractions of inches and degrees, measuring what lies before them with the precision and detail of a microscope, finding distinctions where previous generations might have found only blurs. Yet, each gun they produce carries within it the sum of the past. The powder that each cartridge contains can trace its evolution back two, three, four hundred years and more. The machine that molds the cheekpiece has roots in the wooden wheel and the forge that stood at the side of the crooked creek where long rifles were made by hand.

There are always numbers to talk about when discussing about guns. Four billion dollars’ worth of wages directly involved in manufacturing alone; ten billion overall in the industry. Nearly fourteen million hunters in America, who together spend some $38 billion a year on their pursuit. Six million—the number of guns manufactured in the U.S. in a single year.

But numbers mean nothing without people: the woman in the factory at Colt, inspecting the latest example of the gun that won the West; the guy truing a Remington 700 action in his garage workshop for a soldier going overseas; the hunter stalking deer in the Minnesota woods.

You can get a little fancy talking about guns. You can become a bit starry-eyed thinking about history. You can forget the rough spots.

That’s not fair. Real life has been messy, bloody, complicated. Not a straight line.

That doesn’t mean it hasn’t been triumphant, victorious, glorious, and wonderful along the same way. Good has triumphed over evil; we have come to terms with our darker selves. America has won its freedom, preserved it, and extended it to others. Guns are not perfect—no model in our history has come to market fully finished without flaw. Neither have we. Man and gun have improved together, sometimes with ease, more often with great struggle and sacrifice.

Our victories in the past are no guarantee for the future. What has been won can always be lost. But the past can show us the way to the future. It can give us hope: The men and women in this book did it; we can too.

When you pick up a gun, whatever model, think a little on Sergeant Murphy taking aim on the battlefield, then going home to start a new life with his young wife, busting the forest into productive land, raising kids. Think about the policemen braving the insanity that was Baby Face Nelson, taking bullets so that others might live. Think about Zip Koons, nervous and fearful in that barn in rural France, yet always doing his job, and just his job. Think of the SWAT team guy trying to put the hostage taker in his crosshairs so he can’t kill the child he’s dragging by the hair. Think about the soldier on the front line preserving freedom.

Think of yourself, and your connection to history. Ask yourself: What do you owe to the American soul you’re tied to, and how are you going to pay it forward?

by Taya Kyle

This book has been a real journey for me. It began more than a year ago, when Chris shared with me the idea for

American Gun

. He was energized by the project. I loved seeing his passion grow as he dove into the research and discovered fascinating facts. And then, after his death, I was honored to be involved in carrying out his vision. Working on it, I felt deeply connected not just to American history, but to Chris himself. I hope you felt the same.

Traveling through the past with Chris in

American Gun

brought to life incredible turning points in history, from the streets of the old West to the battlefields of the Civil War, right up to the modern day. It strikes me that while times and guns change, the human experience remains constant. There will always be good. There will always be evil. There comes a time when honest debate, serious diplomatic efforts, and logical arguments have been exhausted and only men and women willing to take up arms against evil will suffice to save the freedom of a nation or a continent.

What makes us uniquely American is that when the chips are down and freedom is threatened, our men and women have always answered this call and have been willing to put it all on the line to fight battles both here and abroad. I find their stories inspirational. The world is full of people tempted to live not on their own merit, but on a path forged by others. Still others maliciously prey on the defenseless and the innocent. I feel blessed to have been reminded by this project of the humanity and strength of those who believe in giving their all to protect and serve the greater good.