Read American Gun: A History of the U.S. In Ten Firearms Online

Authors: Chris Kyle,William Doyle

Tags: #History, #Non-Fiction

American Gun: A History of the U.S. In Ten Firearms (7 page)

Library of Congress

Some historians accuse Ripley of dooming many thousands of American troops to unnecessary carnage and death by prolonging the war. I’m inclined to agree. Thanks to the untalented Mr. Ripley, hardly any breechloaders or repeaters were in the hands of Union forces by the end of 1862, a full year and a half after the President’s early tests. Pretty much the only repeaters in Unions hands at all came from a small order for Spencers by the Navy, which was out of Ripley’s reach, and the guns soldiers bought themselves.

I suppose you could take Ripley’s side by saying he had no way of knowing how long the war would go, or what gun platforms would gain traction. Besides worrying about paying for everything—a unique and unusual concern for a government official, in my experience—he was also trying to avoid the headache of figuring out new supply pipelines to feed multiple forms of ammunition to the far-flung troops.

But let’s face it: the guy was a threat to national security.

Luckily for America, Lincoln eventually managed to fire him, aided in part by an anti-Ripley revolt that erupted in 1862 as some units demanded to be armed with the latest guns, especially the Sharps rifle.

The Sharps was a breech-loading, single-shot, percussion-cap rifle that a trained soldier could load and fire up to ten times a minute, or three times faster than a Springfield. A sleek forty-seven inches long, a trained marksman could reliably hit targets at six hundred yards or more with it. The gun was easy to handle and reliable, and it became a favorite of civilians as well as professionals heading toward the frontier. “The Sharps mechanism made the gun so easy to use, anyone could fire it and stand a fairly good chance of hitting something—or someone,” wrote historian Alexander Rose.

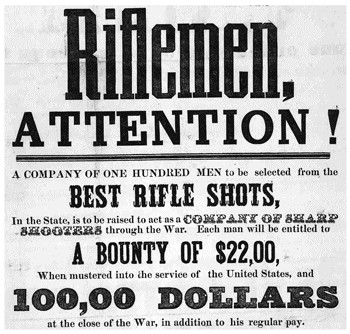

The most celebrated member of Berdan’s Sharpshooters, “California Joe” (aka Truman Head), and his 1859 Sharps rifle. Below: A Union recruiting poster seeking “the best rifle shots.”

Library of Congress

Even more popular in the Army was a carbine version, which featured a shorter barrel—which is, after all, the main difference between a “rifle” and a “carbine.” The highly accurate and easy-to-carry weapon was a favorite with mounted cavalry, both North and South. It should be said that one of the reasons the Sharps was liked by soldiers was its reliability. The gun was well-designed and well-made. The quality of manufacturing was one reason for the higher price; you get what you pay for. Ripley might not have thought so, but the less-well-produced Southern clones proved the point. They didn’t hold up nearly as well.

That’s one of the things historians are talking about when they write that the North’s manufacturing abilities won the war. The days of hand-built guns were past. Armies were now too big to be supplied by a handful of craftsmen toiling away in local workshops. An industrial base and skilled factory workers were nearly as important to winning a battle as great generals were.

The precision of the Sharps meant that marksmen could play an important role in the battle. Special units were created. Among the most effective were Colonel Hiram Berdan’s 1st and 2nd U.S. Sharpshooters regiments, whose weapons of choice were the Sharps rifles. These specialized, highly trained marksmen, skirmishers, and long-range snipers wore green camouflage, and, thanks to the easy-loading Sharps design, shot safely from concealed positions, such as flat on the ground or from behind trees. They also carried rifles equipped with the earliest telescopic sights.

To qualify to join the elite unit, you had to be able to put ten shots inside a ten-inch-wide circle from two hundred yards. The Sharpshooters gave the Union army a powerful combat edge and fought effectively in many major battles of the Civil War, including Mechanicsville, Gaines’s Mill, the Second Battle of Bull Run, Shepherdstown, Antietam, Gettysburg, Yorktown, Vicksburg, Chattanooga, Atlanta, Spotsylvania, and Petersburg.

But as fine a weapon as the Sharps and other breechloaders from the period may have been, in my opinion the real badass infantry weapon of the Civil War was the Spencer Repeater. And in early 1863, it made its first big appearance on the battlefield. It was a shocking debut.

By now, small batches of at least 7,500 Spencers had made it into the regular Army pipeline, and some commanders were even shelling out their own money to equip their units with the gun. One Colonel John T. Wilder of Indiana was so impressed by a field demonstration of Spencers that he lined up a loan from his neighborhood bank to buy more than a thousand Spencer repeating rifles for his “Lightning Brigade” of mounted infantry.

Colonel Wilder’s commander was Major General William S. Rosecrans, whose Army of the Cumberland was tasked to rout the Rebs from Middle Tennessee. Though slow to move against Confederate General Braxton Bragg and his Army of Tennessee, once Rosecrans got moving he did so with style. In the last days of spring 1863, Rosecrans began a series of maneuvers that are still studied today for their near flawless execution. Wilder and his men, now armed with those Spencers he financed, were smack in the middle.

The brigade was a one-off outfit, a hybrid of cavalry and infantry at a time when those two forces were very separate animals. Colonel Wilder was a bit of a different beast himself. Hailing from New York’s Catskill Mountains, he commanded a collection of infantry units totaling some fifteen hundred foot soldiers, along with a detachment of artillery. His first assignment was to run down a rebel cavalry unit that had made mincemeat of Rosecrans’ supply line. You don’t need to know much about combat to guess how that went; pretty much every horse I’ve seen is faster than any man I’ve met. Wilder came away from the assignment a wee bit frustrated.

Possibly a member of Colonel Wilder’s “Lightning Brigade” of mounted infantry—armed with a Spencer rifle.

Library of Congress

But from that setback came a solution—he asked permission to mount his infantry. Wilder wasn’t transforming his brigade into horse soldiers. He wanted a force that could move at lightning speed, then dismount and fight. And when he said fight, he meant

fight

. Besides the repeaters, he armed his men with long-handled axes for hand-to-hand combat. Here was an officer who fully understood the phrase

violence of action.

Colonel Wilder also appreciated the meaning of the word

charge

, which is what he did on June 24, 1863, when tasked to take Hoover’s Gap, a key pass Rosecrans needed to outmaneuver his enemy. Wilder’s men slammed through the gap like a bronc busting out of its gate. They routed the 1st Kentucky Cavalry, then pushed well ahead of the main body of infantry they were spearheading.

The Rebs counterattacked ferociously, sending two infantry brigades and artillery against the Northerners. Though badly outnumbered, Wilder’s men held their ground. The volume of fire poured out by the Spencers—nearly 142 rounds per man—was so large that the Confederates thought they were facing an entire army corps. The rebel lines collapsed into retreat.

“Hoover’s Gap was the first battle where the Spencer Repeating Rifle had ever been used,” Wilder later wrote, “and in my estimation they were better weapons than has yet taken their place, being strong and not easily injured by the rough usage of army movements, and carrying a projectile that disabled any man who was unlucky enough to be hit by it.” He added, “No line of men, who come within fifty yards of another armed with Spencer Repeating Rifles can either get away alive, or reach them with a charge, as in either case they are certain to be destroyed by the terrible fire poured into their ranks by cool men thus armed. My men feel as if it is impossible to be whipped, and the confidence inspired by these arms added to their terribly destructive capacity, fully quadruples the effectiveness of my command.”

One of Wilder’s soldiers wrote of the Spencer that it “never got out of repair. It would shoot a mile just as accurately as the finest rifle in the world. It was the easiest gun to handle in the manual of arms drill I have ever seen. It could be taken all to pieces to clean, and hence was little trouble to keep in order—quite an item to lazy soldiers.”

“Those Yankees have got rifles that won’t quit shootin’ and we can’t load fast enough to keep up,” said a Confederate soldier who was on the losing end of the Battle of Hoover’s Gap. After another Tennessee battle, a Confederate prisoner asked his captors, “What kind of Hell-fired guns have your men got?”

The performance of the Spencer Repeater that June day in Tennessee marked the true dawn of the multiple-shot infantry gun, an era that would dominate the battlefield of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.

A week after Hoover’s Gap, North and South faced off in an epic battle destined to be remembered for centuries. It was the Battle of Gettysburg, and while the vast majority of guns fired there were rifle-muskets, breechloaders and repeaters appeared at critical moments to help tip the scales in favor of the North.

Fighting was reaching its climax on the third day of the battle, July 3, 1863, when Confederate General James Ewell Brown “Jeb” Stuart and his legendary cavalry force prepared to smash deep into the rear of the Union forces guarding Cemetery Ridge. Stuart’s maneuver was intended to support the Rebs’ frontal assault on the Ridge, flanking the Northerners and cutting their supply lines. If Stuart’s cavalry managed to penetrate the Union rear, there was a good chance that Union General George Meade would be forced to siphon off troops and leave the main force disastrously exposed to what is now known as Pickett’s Charge.

The only thing between Stuart and the vulnerable Union rear was a cavalry division commanded by General David McMurtrie Gregg. His forces included a brigade of cavalry temporarily attached to his command and led by the Union Army’s newest and youngest general, twenty-four-year-old George Armstrong Custer. Custer has gone down in history as a peacock of a leader, a commander who dressed so flamboyantly that one observer compared him to “a circus rider gone mad.” He’s also considered a ridiculously bold general, rash or daring depending on your point of view. But no matter how you look at it, he had courage and guts in spades.