AMERICAN PAIN (31 page)

Authors: John Temple

7

Early in 2009, Jennifer Turner flew to Kentucky to take a look at the flip side of the pill mill disaster—the Appalachian front.

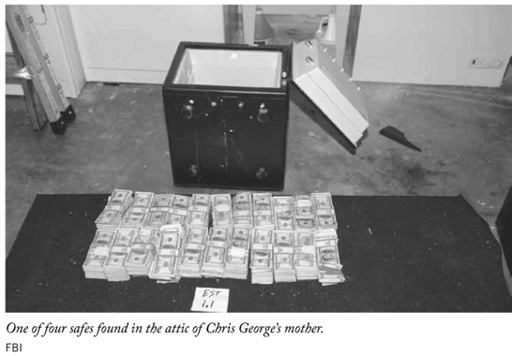

The FBI special agent was no longer working alone. She was now heading up a rapidly growing task force that included the IRS, the US Attorney’s Office, the Broward and Palm Beach sheriff’s offices, local police departments, and the initially reluctant DEA. It had been only a few months since Turner had overheard the group of cops talking about pill mills at the watercooler, but there was a fresh urgency around her investigation. The state’s prescription drug overdose death rate had risen to eleven a day, topping cocaine’s. Florida doctors and pharmacists were distributing almost twice as many oxycodone pills as the next-highest state, Pennsylvania.

*

All the federal agencies now agreed; something had to be done.

Turner’s partner on the Kentucky trip was a broad-shouldered DEA special agent named Mike Burt, a former cop with an expertise in wiretaps. In Lexington, Turner and Burt met with members of the Appalachia High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area (HIDTA) task force to trade information and discuss their shared problem. They decided that the HIDTA team would focus on sponsors and traffickers in their area, and the Florida task force would go after the biggest pill mills.

The special agents also interviewed anyone who could tell them more about the beach-to-mountains pill pipeline. They met with people like Barry Adams, a HIDTA member and a deputy sheriff of Rockcastle County. Adams was a farmer when he wasn’t working, and he looked the part in boots, jeans, and flannel. Like any Kentucky lawman, Adams was long familiar with 10-milligram Lortabs and 40-milligram or 80-milligram OxyContin. But the first time the sheriff’s office had run across oxy 30s from Florida was the first day of 2009, when a young fellow named Stacy Mason had died on the Mason family farm.

Then, one cold afternoon ten days after Stacy Mason died, Adams was off-duty when he saw two men exchange something in the parking lot of Rose’s One Stop gas station in Brodhead. One of the men drove away in a gray pickup truck, and Adams followed him. The truck wove across the centerline, other cars swerving to avoid it, before it slammed into a ditch. Adams tried to conduct a sobriety test, but the driver could barely stand. Adams searched him and found a magnetic key holder containing a bunch of pills, including some he’d never come across before: twenty-five round white tablets marked with 446 ETH. He looked them up and found they were 30-milligram oxycodone pills, manufactured by Ethex Corporation in St. Louis, same dosage as the ones Stacy Mason’s mother had found on his body. Oxy 30s were new to Rockcastle County, and now the sheriff’s office had come across them twice in less than two weeks.

That was the beginning. Adams and the other HIDTA members kept hearing more and more information about what they began calling “that Florida dope.” Details about the new pill pipeline kept piling up, arrest by arrest, interrogation by interrogation.

The pill smuggling spread like a contagion, most often through family relationships, though police in West Virginia said Detroit gangs had moved into Huntington to take over the oxy trade. To Adams’s mind, the rural trafficking networks grew like a spider’s legs. One person—usually the head of a marijuana-growing or meth-dealing family—would begin sponsoring pill runs to Florida. The runners themselves were usually addicted to the pills. This gave the sponsors a hold over the runners, because addicts were always out of money and pills and would therefore make any deal. But junkies were terrible employees, always getting arrested or overdosing on the road or claiming the pills had been stolen.

A few of the most enterprising runners would eventually save a little money and begin sponsoring their own mules. Because the drugs were legal, the pill-running business didn’t have the same barriers to entry as, say, the cocaine trade, where you had to know a supplier. Anyone with a car and a few hundred bucks could make a pill run. And profits from one run were enough to sponsor a carful of mules.

The pipeline inspired its own lingo. For self-evident reasons, the junkies called the oxycodone 30-milligram pills made by Mallinckrodt “blues,” and the traffickers began calling I-75 “The Blue Highway.” State police staked out the Tennessee-Kentucky border, pulling over multi-passenger cars in what they termed “pill stops.” Allegiant Air offered a multitude of cheap round-trips between the mountains and South Florida, and the planes were so packed with drug runners that the flight was nicknamed “The Oxy Express.” Observers found it interesting that the Allegiant planes were the same powder blue as the oxycodone pills.

Police in the states between Kentucky and Florida began to figure it out. If a multi-passenger car with Kentucky tags was heading north through Georgia, state troopers would find a reason to pull it over. They’d often find not just pills but brochures and business cards from clinics and pharmacies, and handwritten ledgers that detailed travel expenses for the sponsor. Sometimes the traffickers behind the wheel were high or they had illegal drugs along with the pills, which made it easy to make an arrest. If half the pills were gone from a twenty-eight-day prescription that had been issued the day before, that was probable cause to suspect drug dealing, and the cops would confiscate the pills. Some traffickers had visited multiple doctors and had more than one prescription for oxyco-done, which was illegal. Those were relatively easy arrests to make.

But as the racket had matured, the traffickers were wising up, adapting to police pressure. Word got around that patients shouldn’t sell their pills until they were safely home so their pill counts wouldn’t be short if they got pulled over. Doctor shoppers who went to multiple pain clinics began to visit FedEx stores in between each doctor’s visit, mailing home the pills so they wouldn’t be caught with more than one oxycodone prescription at a time. Sometimes, patients would drive just over the Georgia line, then rent a car so they could slip past police who were on the alert for Tennessee or Kentucky or West Virginia plates. And police rarely found illegal drugs in pill runners’ cars anymore.

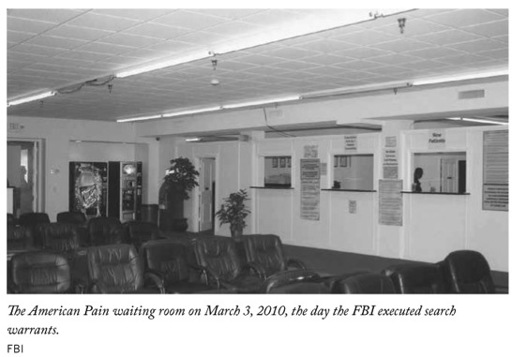

As major Kentucky sponsors grew into kingpins, it became too complicated to make all the arrangements in Kentucky, handing out as much as $2,000 apiece to a carload of addicts in the hope that they would return intact with the pills. So a few of the biggest operators in Kentucky sent subordinates to live in South Florida, renting them a car and a long-term hotel room or even a bungalow. The sponsor in Kentucky would organize and send down the groups, and the coordinator in South Florida would take over from there, meeting the groups, giving them directions and cash, telling them which clinic employees to connect with, the peculiarities of specific doctors, explaining the unwritten and written rules of the pain clinics, guiding them through the process. The pill runners would meet the coordinator in the clinic waiting room. Sometimes they hadn’t met the coordinator before, so one coordinator took to wearing a court jester hat or a Rastafarian hat with fake dreadlocks so he’d be easy to pick out in the waiting room. The runners were told: Look for the guy in the funny hat—he’ll hook you up.

One day during their trip to Kentucky, Turner and Burt learned that a group of pill runners had wrecked while driving back from Florida. One of the traffickers was in the Lexington County Detention Center, and the special agents were invited to talk to him. Turner and Burt went to the jail and took seats in an interview room. Turner’s back was to the door; Burt was sitting on the other side of the table. The door opened behind her, and Turner saw Burt’s eyes widen in astonishment. She turned around to see a prisoner being led into the room. Bloody bandages concealed his massively swollen face and left ear. The accident had nearly severed the flesh from the front of his skull, and doctors had stitched his face back on.