Amy & Roger's Epic Detour (23 page)

“Want a ride?” he yelled over the sound of the mower. I shook my head, and he killed the engine, filling the night with silence. “Want a ride?” he repeated, apparently thinking I hadn’t heard him.

“It’s okay,” I said. “Thanks, though.” Walcott shrugged, then reached back to pull on his headphones again. “Walcott,” I said quickly, before he left and before I could think about what I was doing. I rested my hand on the mower, which was surprisingly hot. “Do you like driving this? Is it fun?”

“Yeah,” he said, smiling at me. “It’s a good time. You want to give it a shot?”

I looked up, and heard my father’s voice in my head clearly, as though it hadn’t been months since I’d heard it at all. “There’s an art to this, my Amy,” I could hear him saying. “I’d like to see you give it a try.”

“That’s okay,” I said, hand still on the mower. “My father—” My voice snagged on the word—it felt rusty. I forced myself to go on. “He would have wanted to. He would have loved that.” I felt my breath begin to catch in my throat and knew that I’d reached the point of no return. I looked up at Walcott. “Can I tell you something?” I asked, hearing my voice shake, feeling a hot tear hit my cheek, and knowing there was no going back.

“Sure,” he said, climbing down from the mower.

I closed my eyes. I hadn’t said this out loud yet. To

anyone

. But now it wasn’t that I couldn’t say it—it was that I couldn’t not say it any longer. “He died,” I said, feeling the impact, the truth of the words hit me as I said them out loud for the first time. Tears ran down my face, unchecked. “My father died.” The words hung in the night air between us. This wasn’t ever how I imagined I’d say it for the first time. But there it was, like Walcott had said. A truth, told to a stranger, in the darkness.

“Oh, man,” Walcott said. “Amy, I’m so sorry.” I heard that there was real feeling in this, and I didn’t brush it away, like I had everyone else’s condolences. I tried to smile, but it turned trembly halfway through, and I just nodded. He took a step closer to me, and I felt myself freeze, not wanting him to hug me, or feel like he had to. But he just took his headphones off his neck and placed them over my ears.

Loud, angry music filled my head. It was fast, with a pounding beat underneath driving the electric guitars. There were lyrics, but no words I could make out, and after all my talky musicals, it was something of a relief. I placed my hands on the side of the headphones and just let the music sweep over me, pushing all other thoughts from my head. And when the song was over, I took the headphones off and handed them back to Walcott, feeling calmer than I had in a long time. “Thanks,” I said.

He slung them back around his neck, then turned to his mower and pulled down a black patch-covered backpack. He unzipped it and dug around until he came out with a CD, which he extended to me. It looked homemade, in a yellow jewel case. “My demo,” he said. I reached for it, but he didn’t let go, looking right into my eyes. “You know what my grandma used to say?”

“There’s no place like home?” I asked, trying again for a smile, this one less trembly than before.

“No,” he said, still looking serious, still holding on to his end of the CD. “Tomorrow will be better.”

“But what if it’s not?” I asked.

Walcott smiled and let go of the CD. “Then you say it again tomorrow. Because it might be. You never know, right? At some point, tomorrow

will

be better.”

I nodded. “Thanks,” I said, hoping he knew I didn’t mean just the CD. He nodded, climbed back up on his mower, started the engine, and headed off again.

I took a moment for myself, alone in the darkness by the seventh hole—par five—of the Wichita Country Club. Then I put my flip-flops back on and headed back. Drew and Roger were waiting for me where the course began and grass met gravel. Roger looked worried, and my face must have betrayed something of what had just happened, since he didn’t stop looking worried when he saw me.

“You get lost?” Drew asked.

I held up the CD. “Ran into Walcott,” I said, trying to keep my voice light. “He gave me his demo.”

“Told you!” said Drew. We headed out, and I saw that the girl on the practice court was still there, now practicing her serve, tossing the ball high up above her head before slamming it back to the wall.

Drew insisted on driving us back to the car, saying that it was on his way out. It seemed that while I’d been gone, Roger had been telling him about Highway 50, and they picked up this conversation again.

“You can’t believe it,” Roger said. “It just goes on and on, and you think it’s never going to end.”

“But then it does,” Drew said. “Wow. That’s a great story, dude.”

“I’m serious!” said Roger. “You think it’s going to last forever.”

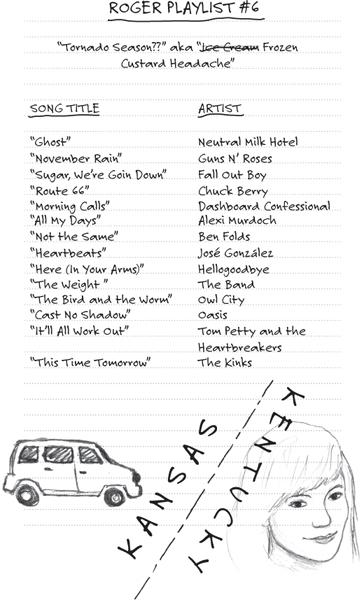

“But nothing lasts forever,” Drew said, and then he and Roger sang together, “Even cold November rain.” I looked from one to the other, baffled.

“Seriously?” asked Drew, catching my expression in the rear-view mirror. “Magellan, get this girl some GNR.”

I had no idea what he was talking about, but I didn’t have time to ask, because a few seconds later, the car stopped outside the country club gates. I looked out and saw the Liberty, parked in a pool of streetlight. I was unexpectedly glad to see it again.

My house might be in the process of being sold by an overly friendly Realtor, and my family might be gone or scattered across the country, but the car seemed welcome and familiar and, mile by mile, more like home.

We all got out, Drew pulling the front seat forward for me. He extended his hand again, and this time I took it, giving him a small smile that he returned, broadly. Drew and Roger hugged and hit each other on the back a few more times, and then Roger walked to the Liberty, leaving me and Drew alone. “It was nice to meet you,” he said.

“Thanks for the NuWay,” I said. “Crumbly is good.”

“Didn’t I tell you? Do me a favor,” Drew said, slamming the driver’s-side door closed and leaning a little closer to me. “Keep an eye on my friend Magellan, would you? Be his Sancho Panza.”

I stared at Drew, surprised. My father had suddenly intruded into this conversation, when I hadn’t been expecting him. “What did you say?” I asked.

“Sancho Panza,” Drew repeated. “It’s from

Don Quixote

. The navigator. But listen. The thing about Magellan is the thing about all these explorers. Most of the time, they’re just determined to chase impossible things. And most of them are so busy looking at the horizon that they can’t even see what’s right in front of them.”

“Okay,” I said, not really sure what he meant. Was he talking about Hadley? “Will do.”

“Drive safe,” he called to Roger, who, I saw, was already in the car and nodded in response.

I had just opened my door when I heard Drew let out an impressive stream of expletives. I turned to see him peering sadly in through the driver’s-side window. “Keys?” Roger called.

“Seriously?”

Drew sighed and pulled his phone out of his pocket. “Don’t worry about me,” he said with a shrug. “Go on. I’ll be fine.”

I climbed into the car, shut the door, and looked around its familiar gray interior and, most familiar of all, Roger sitting behind the wheel, smiling at me. “Ready?” he asked.

“Ready,” I said. I took Roger’s glasses out of his case. Seeing the smudges on the lenses, I gave them a quick polish with the hem of Bronwyn’s shirt. He put them on, started the car, and we pulled out onto the road. In my side mirror, I could see Drew waving. He continued to wave as we drove away, until he got smaller and smaller and finally faded from view.

Where they love me, where they know me, where they show me, back in Missouri.

—Sara Evans

Around midnight, it started to rain.

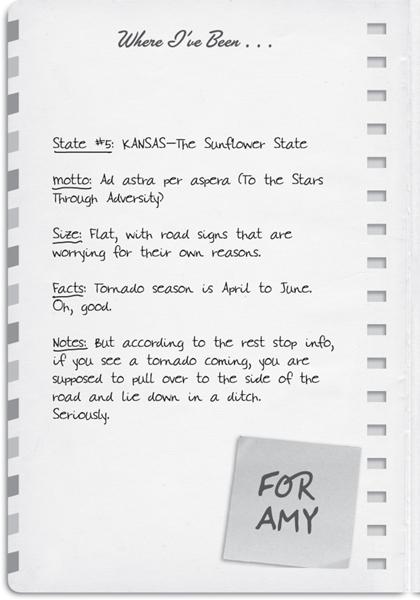

We’d been driving through Kansas in the dark for three hours, not speaking much. I’d been looking out the window, feeling the reverberations of what I’d told Walcott still coursing through me, like aftershocks following an earthquake. I’d said it out loud. I had. And it hadn’t made things worse—the world hadn’t ended. But I didn’t feel a lot better, either. It was almost as though by saying the words out loud, I’d summoned it in a more real way, because I was now having a hard time thinking about anything else. My mind kept circling around and around the things I wanted to think about the least.

The rain was a welcome distraction. I leaned over and showed Roger how to adjust the wiper settings, and I looked ahead to the highway, obscured and made somehow beautiful by the rain streaking across the windshield, blurring the red lines of brake lights ahead of us and the white lines of headlights to the left of us, no sound in the car except Roger’s mix and the constant, muted

thwap

of the windshield wipers.

The rain was light at first, just a few droplets, but then it was as though the endless sky above us had opened, and bucketful after bucketful was being tossed down onto the car. “Wow,” Roger said, fumbling with the wiper settings again. I leaned over and turned them up so they were going at their fastest setting—

thwapthwapth-wapthwapthwap

. “Thanks,” he said.

“Sure.” I leaned back and looked out into the darkness, at the rain droplets streaking diagonally across my window. I’d always felt safe driving inside cars at night when it rained. I knew most people—like Julia—had always hated being in cars when it rained, especially at night. She said it scared her. But it had never bothered me. Especially since I now knew that the worst could happen in broad daylight on a sunny Saturday morning, fifteen minutes from home.

“You used to drive this car?” Roger asked, glancing over at me.

“Sure,” I said, propping my feet on the dashboard.

“If you ever want to drive,” he said, a little tentatively, like he was considering each word before he spoke it, “I mean, you absolutely could. I would be fine with that.”

I put my feet down and sat up straighter. “Should we stop?” I asked. “Are you too tired?”

“No, I’m fine,” he said. “I’ve got at least two more hours in me tonight. I just … wanted to let you know that I’d be okay with you driving.”

Something about the way he said this made me go still. Did he know what had happened? I’d thought he didn’t, but maybe that was just what I’d wanted to think. And maybe he hadn’t just been perceptive when Drew had been driving too fast for me. Maybe he’d known why it bothered me, and had known this whole time. “I don’t want to drive,” I said, trying to keep my voice steady, but hearing it quaver a little despite my best effort.

“Do you want to talk about why?” he asked. He glanced at me.

I stared at his profile, feeling my heart hammering. The car didn’t feel so safe anymore. “Do you know what happened?” I asked, hearing that my voice was already sounding strangled.

Roger shook his head. “No,” he said. “I just think that maybe you should talk about it.”

My heart was pounding in my chest. “Well, I don’t want to,” I said as firmly as I could.

“I just …” He looked at me, and I saw that his glasses had gotten smudged again somehow. I could practically see a whole fingerprint on the right lens. I chose to focus on this, and not the way he was looking at me. Like he was disappointed in what he was seeing. “You can talk to me, you know.”