Authors: John Askill

Angel of Death

First published in Great Britain in 1993 by

Michael O’Mara Books Limited

9 Lion Yard

Tremadoc Road

London SW4 7NQ

This electronic edition published in 2013

ISBN: 978-1-78243-245-6 in ebook format

ISBN: 978-1-85479-182-5 in paperback print format

Copyright © 1993 by John Askill and Martyn Sharpe

Every reasonable effort has been made to acknowledge all copyright holders. Any errors or omissions that may have occurred are inadvertent, and anyone with any copyright queries is invited to write to the publishers, so that a full acknowledgement may be included in subsequent editions of this work.

All rights reserved. You may not copy, store, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

The moral right of the authors has been asserted.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Designed and typeset by Florencetype Ltd, Kewstoke, Avon

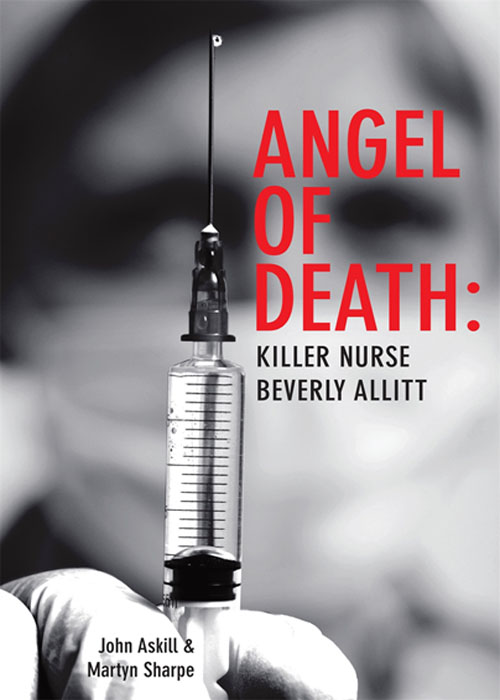

Cover image by AlexeiLogvinovich / Shutterstock

2 Liam – ‘Little Pudding Pants’

6 Claire – ‘Crikey, Not Another One’

The authors are grateful for the help they have received from the families touched by the events recorded in this book.

Peter Phillips struggled to fight back the tears as he carried a tiny Christmas tree, complete with decorations, into the graveyard. Despite his slight frame Peter was fit, active and physically strong which had stood him in good stead when he’d worked as a lorry driver. At forty he still had the impish good looks and sense of fun that had captured the heart of his bride, Sue, when she was just half his age. Now he was broken and so, too, was she.

Sue, blonde, pretty and slightly taller than Peter had been just seventeen when they’d met. He was thirty-four, twice divorced, with two daughters aged eleven and nine at home. Three years after their wedding Sue gave birth to son James and they’d been blissfully happy, though now, on this cold, sunny December day, she battled to keep a brave face as she walked by his side, her mind numb with despair.

When James was three they had been blessed with twins, daughters Becky and Katie, a gift from God. But, as they picked their way through the tombstones, they began to question what kind of a God was this that could give and cruelly take away so quickly.

Quietly, with the watery winter sunshine reflecting on the new white marble headstone, Peter placed the miniature Christmas tree on one side of Becky’s grave and laid a small posy of flowers on the other, determined that their baby should not be allowed to miss out on what would have been her first Christmas. Hardly a word was spoken between the two parents as Sue, tears gently rolling down her cheeks, laid a huge wreath, in the shape of a giant teddy bear, on the newly made grave. Becky had only been nine weeks old when Peter had watched her die. She’d been screaming in his arms, her face contorting in agony.

Now Becky lay at peace in this quiet corner of Lincolnshire, in the churchyard behind St John’s Church, Manthorpe, on the outskirts of Grantham. She’d been buried in a tiny white coffin, lined with pure white duck down, with two teddies from her cot placed alongside her, and Sue had tossed a red rose into the grave as they’d lowered her coffin into the ground.

The grief had almost been too much to bear on that awful April night when she’d died. But there had hardly been time for Peter and Sue to mourn or ask questions before suddenly, and without warning, twin sister Katie had been struck down too. Katie’s life had hung by a thread on that same dreadful day. Sue and Peter had been in torment because, as Becky was lying in the mortuary at one end of the Grantham and Kesteven General Hospital, Katie was fighting to survive on Ward Four, the Children’s Ward, at the other end. Frantically

doctors, nurses and the hospital emergency team had worked on, finally succeeding in saving Katie.

Afterwards, the doctors, who could find no other cause, said that Becky had died from a ‘cot death’, but they couldn’t explain what had happened to Katie. Now it was almost Christmas and, as Sue and Peter arrived at Becky’s grave, they were just thankful they still had Katie alive.

Thirty miles to the north, Robert Hardwick pushed his disabled wife, Helen, in her wheelchair towards the grave of their eleven-year-old son Timothy. Helen had been perfectly healthy, full of vitality and energy before she had become pregnant, but then she’d suffered a stroke just two weeks after Timothy had been born. Six months later doctors confirmed that baby Timothy was also terribly handicapped. But, for all that, Timothy had been a joy. Now her son lay buried in the cemetery at Chilwell, on the outskirts of Nottingham, and, as it was Christmas, they wanted to offer a silent prayer for the child they had lost. Timothy, their only son, had died unexpectedly on Ward Four of the Grantham and Kesteven General Hospital.

Little Liam Taylor was seven weeks old when his mum Joanne had taken him to Ward Four. He hadn’t been critically ill. The family doctor had been treating him for a bad cold but, when it didn’t improve, he diagnosed bronchiolitis, a severe chest infection, and, finally, their health visitor suggested

little Liam needed to go to hospital. It was simply a precaution but, within forty-eight hours, he was dead. Doctors diagnosed a massive heart attack though they were unable to discover what had caused it. Liam was buried in the graveyard at St Sebastian’s church, in the village of Great Gonerby, just outside Grantham. The white marble headstone was engraved with a teddy bear and bore the inscription: ‘Little Child Come Unto Me’.

In the village of Balderton, fifteen miles north of Grantham, Sue and David Peck were battling to come to terms with their loss. Daughter Claire was their first and only child, a treasure, always laughing, so full of life. She was fifteen months old and just beginning to talk. She had gone into Ward Four in the throes of an asthma attack. The family doctor had told them it would only be a short hospital stay and that she would soon be home. Then, inexplicably, she’d died. The specialist had put his head in his hands and said it was a chance in a million that they had lost her.

In sixty days in February, March and April 1991, three babies and an eleven-year-old boy had died. Nine other children on Ward Four, the youngest aged eight weeks and the oldest six years old, had suffered unexplained cardiac arrests or respiratory failures and recurring fits. There had been twenty-four incidents.

Normally, the hospital’s casualty ‘crash team’ would expect to be summoned to one or two life-threatening

emergencies each year on Ward Four, but they had never been so busy, never been called out so often, never saved more children, lost more children, than in those hectic months.

In rapid succession Kayley Desmond, Paul Crampton, Henry Chan, Bradley Gibson, Katie Phillips, Christopher Peasgood, Christopher King, Patrick Elstone and Michael Davidson had become very ill. Some had recovered quickly. Others had been to the brink of death but survived, so near to dying that clergymen had been called to christen them where they lay in the hospital, nurses stepping in as makeshift godparents.

What made it worse for most of the parents was that their children had been in no real danger until they were placed in the care of the hospital.

Doctors were baffled. Could it be some kind of ‘bug’, affecting children only in one ward of the hospital? Ward Four was swabbed inch by inch and the walls scrubbed. They thought it might be a deadly strain of meningitis or even Legionnaires Disease, but when they found nothing the ward carried on as usual.

Could it be just bad luck? Some of the nurses thought it was simply a run of tragic events. After all, they were treating sick babies and children, and sometimes they died.

No one suspected that the unthinkable could be happening – that there was an evil serial killer stalking the ward, poisoning children and babies.

It took the death of Claire Peck, the fourth victim, finally to convince the hospital authorities that it was time to call in the police. Questions would later be asked as to whether they should have reacted sooner and whether lives could have been saved. But when the hospital made the call to Grantham police station, no one knew what was happening or why.

The Detective Sergeant who came to the hospital listened to the unfolding story in amazement. He went back to the police station and told a colleague: ‘I’m out of my bloody depth here.’ This was a job for his bosses in headquarters at Lincoln, twenty-five miles away to the north.

Three days later, on 1 May 1991, alerted to the suspicion that something very strange was happening, Detective Superintendent Stuart Clifton, head of Lincolnshire CID, arrived to probe the bizarre sequence of events on Ward Four at the Grantham and Kesteven General Hospital.

More than most Stuart Clifton was a cautious man, a meticulous investigator with a startling eye for detail. He was not immediately convinced that there had been foul play. A lifetime as a policeman had taught him not to jump to conclusions and murder in a children’s ward seemed an unlikely possibility here in rural England. Or was it?

If someone was trying to kill babies and children in the hospital, Supt Clifton wanted to know why, as much as how? What kind of person could do such an awful thing? Were they mad, driven by some dreadful demon? Or were they just bad?

Surely it could not be a nurse or a doctor? Nurses worked long hours for little reward and were affectionately called ‘angels’. They were rightly held in the highest esteem. But, if it was not a nurse or a doctor, then who else had access to the ward? Supt Clifton was accustomed to investigating robberies and murders where there was always a motive. It could be greed, it could be love or jealousy, that had been the spur, but what could cause someone to kill and keep on killing one helpless infant after another, attacking others, week after week, for sixty days? Later, much much later, psychiatrists were to come up with a theory.

Not much happens in Grantham and locals are almost proud of the fact. The ancient, red-brick town which stands beside the notoriously dangerous A1 London-to-Edinburgh trunk road, the Great North Road, has a population of 30,000 and a reputation for being the dullest place in Britain. More than 1000 of its residents thought it was so boring they wrote to the BBC in a nationwide poll in 1981 to claim the title. Some even suggested the best thing to come out of Grantham was the A1 itself.

But it’s a prosperous market town, big enough to command its own Marks and Spencer store, a large Boots the Chemists and Woolworths, and a spacious indoor shopping centre with a multistorey car park, all set on either side of its one main shopping street.

On Saturdays, market-stall holders take over

Westgate and Market Square. The town still boasts two Grammar schools, the King’s School for Boys, founded in the sixteenth century and the Kesteven and Grantham Girls’ School, plus several other secondary schools and a modern College of Further Education.