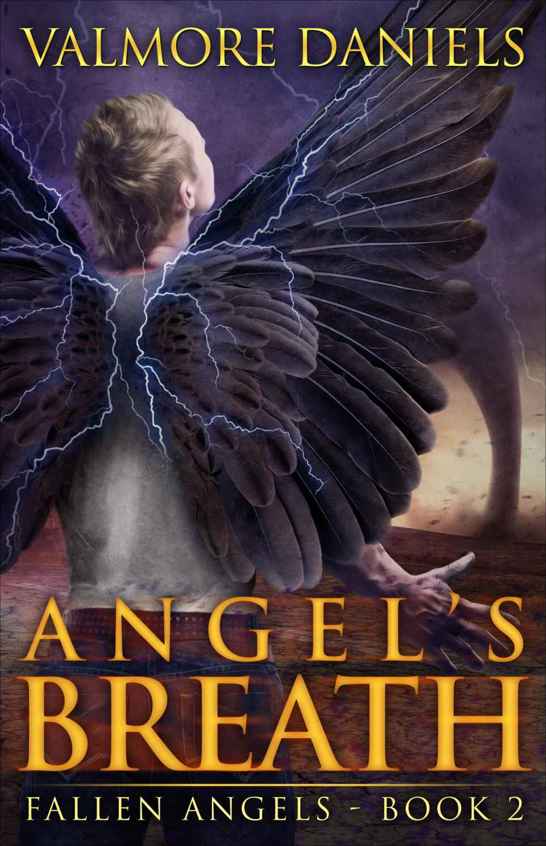

Angel's Breath (Fallen Angels - Book 2)

Angel’s Breath

Fallen Angels - Book 2

by Valmore Daniels

This is purely a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental. This book may not be re-sold or given away without permission in writing from the author. No part of this book may be reproduced, copied, or distributed in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means past, present or future.

Copyright © 2012

Valmore Daniels

. All rights reserved.

Chapter One

Ecce turbo dominicae indignationis egredietur et tempestas erumpens super caput impiorum veniet.

(Behold the whirlwind of the Lord's indignation shall come forth, and a tempest shall break out and come upon the head of the wicked.) – Jeremiah 23:19

“Richard Riley?”

“Yeah, that’s me.”

I looked up at the nurse, and my first impression was she was scowling at me, as if I’d done something wrong.

However, when I blinked my eyes and looked again, she had that clinical look of polite concern. I must have been tired. My eyes were playing tricks on me.

Sitting in the waiting room outside the emergency ward was a crappy way to spend the first hour of my twenty-first birthday. The mixture of fear and boredom was working on me. I had been up before six in the morning, and it was now past midnight; I was exhausted. The constant patter of Seattle rain beating against the windows did nothing to soothe me.

I was glad to get back up. My legs were cramping from sitting for so long.

I held my breath waiting for the nurse to speak again.

“You can see your mother now,” she said. “She’s finally stabilized.” She turned around and retreated down the hall, her soft-soled shoes making a squeaking sound on the polished tile floor with every step.

I thrust my fingers under my glasses to rub my eyes, and then I followed her. I spat the wad of gum I was chewing into my hand and dropped it in a garbage can as I passed the reception desk. It lost its flavor.

We wound our way through a connecting hall into the examination area where they brought my mother. The room was windowless, and large enough to house a dozen beds, each separated by thick curtains on rails attached to the ceiling. The nurse led me to the last room, and drew back the curtain and motioned for me to go in.

I clenched my teeth at the sight of my mother.

There was a pale tinge to her skin, which was pulled so tight she looked inhuman. Her normally blonde hair was dark, thin and matted. An oxygen tube extended from her nostril down over her high cheekbones and behind her ears. A slight wheezing sound came out from between her dry, cracked lips. Her eyes were squeezed shut as if she were in pain.

Though she was still unconscious, she had wrapped her hands around her waist, and she had pulled her knees up to her chest.

“We had to pump her stomach,” the nurse said, and this time her tone was softer, more reassuring.

“Is it bad?” I asked, keeping my voice low. “Is she going to be all right?”

The nurse tilted her head and lifted her eyebrows. “That’s not for me to say. We’ve got her on an IV drip and oxygen. She’ll have a sore throat from the vomiting and the procedure. She’s out right now. We’ll keep her here for observation.”

“How long?” I asked, my voice thin.

“That’s up to the doctor. Maybe a day or two, depending.” A moment later, she said, “According to our records, this is the second time this year she’s been admitted for this.”

I tried to keep my expression blank. “Yeah.”

“We have a treatment facility right here in the hospital, you know. I could bring you some literature.”

When I glanced at her sharply, she said, “There are financing options available.”

“When is the doctor coming back?” I asked.

The nurse pursed her lips, and her tone once more became clinical. “He’s already checked on her. He isn’t scheduled for his next set of rounds until tomorrow afternoon.”

I nodded. “Thank you.” I pulled a plastic-backed chair close to the bed and sat down.

The nurse paused for a moment before stepping out of the room and drawing the curtain closed behind her.

My first impulse was to reach out to touch my mother’s arm, but I stopped halfway. Instead, I rested my chin on my palm, my elbow on my knee.

As far back as I could remember, my mother always had a drink in her hand. When she came home from work, she went directly to the liquor cabinet and mixed herself a cosmopolitan, even before thinking about making dinner for the two of us.

As a kid, I never thought there was anything out of the ordinary about it, except on the rare occasions when I would catch her staring out the window with a tear in her eye, ignoring whatever television program was on at the time. When I asked what was wrong, she would wipe her cheek and smile at me, then ask whether I did all my homework.

During my early teens, as I stayed up later and later, I started to notice that sometimes she never made it to her own bed at night. Many times, by ten or eleven o’clock, she would be passed out on the sofa. By then I was old enough to realize she was going to drink herself into an early grave.

One night when I was fourteen, I confronted her about it. She slapped my face and told me to shut my mouth; it was none of my business.

Until then, I had always thought of us as a unit, mother and son. Sure, we’d had our problems. I was adjusting to being an adolescent, trying to figure out who I was. She didn’t want me to grow up; I knew that much.

Admitting I was getting older meant admitting that one day I would be out on my own and I would leave her behind. In effect, I would be abandoning her. That, I knew, was what she feared the most. My father had split before I was born. I remember thinking I could never leave my mother; it would devastate her. As I grew older, however, the relationship between us changed, and I started to believe I had to get out on my own.

By the time I was fifteen, my friends became more important to me. Soon, enough friction grew between my mother and me that we could barely speak a word to one another without it descending into a shouting match. When you are in that no-man’s land between a child and an adult, it doesn’t register how much everything you do affects the people around you. I admit I had become more and more belligerent and self-absorbed as the years went on; abandoning her emotionally, even while I still physically lived at home.

We got into a few roof-raising fights when she caught me sneaking her into her liquor cabinet a few months before I turned sixteen. At that point, I didn’t care how much she yelled. I figured that she was a hypocrite, and that gave me the right to do what I wanted.

On my sixteenth birthday, she caught me smoking pot in my room. We yelled for hours, and dragged up every bit of ammunition we had. But it was when I called her a ‘drunken bitch’ that she slapped me in the face.

I ran away that night. I believed I was better off on my own. I didn’t see her again until eighteen months ago.

I had hated her for trying to stop me from doing what I wanted when, at the same time, she drank herself into a stupor every night. I thought I was old enough to make my own decisions, and I didn’t need an alcoholic to tell me what to do.

As it turned out, if there was a right way and a wrong way to do anything, I pretty much found a way to make it worse.

My life for the next three years had been one big screw-up after another: dropping out of school; panhandling on city streets; sleeping in fast-food restaurant bathrooms in winter; rooting through trash bins for something to eat. I shoplifted whenever I hadn’t scrounged up enough money to buy what I needed to survive.

It was a wonder I had survived as long as I had without being collared by the cops. Of course, they had finally caught up with me, and a judge had put an end to me living on the street.

Before assigning me to a series of basic skills courses, the first question the prison counselor asked was if I had any employment history. At nineteen, I had no education and no trade. The thought of trying to find a legitimate job hadn’t crossed my mind the entire time I had been away from home. Getting a nine-to-five job had been the last thing on my mind, even though I’d had a good enough role model for it.

As far as I could recall from memory, my mother had never missed a day of work, or been late, however much she drank.

Of course, that was true right up until this year, and that was because of me.

I knew, deep down, it wasn’t my fault that she had drowned her misery in alcohol all these years, but I had no doubts that I was the one who had made it worse for her. I had run away and abandoned her.

Since my release six months ago, I’d tried my best to make life easier for her. At first, it had been good, but over the past three months, things had started going downhill. At times, I believed my return had been worse than my leaving in the first place.

Over the past few months, her drinking had become uncontrollable. She was usually incoherent by eight o’clock, and passed out on the couch by nine every night.

Tonight had been one of the worst. She had gone beyond the point of no return, and had nearly drunk herself to death.

The scene kept playing out in my head:

I had come downstairs for a glass of water before bed and found my mother lying on the living room floor in a pool of her own vomit. I froze in fear. Was she dead?

But there was no time to think. I raced over and felt for a pulse. She was alive, but her breathing was shallow and raspy. I knew there wasn’t time to wait for an ambulance. I picked her up and drove her to the hospital, speeding and running lights like someone possessed.

Over the past two hours—the waiting driving me mad—I had made a dozen vows. Once I got home, I would find and trash all her booze. I knew that wouldn’t stop her. I wanted to get her into a treatment program, like the one the nurse mentioned, but I knew neither of us had the money. With my past, there was no way I could get financing, and my mother had always lived paycheck to paycheck. I racked my brains for a way to make things right. But I couldn’t think.

I felt powerless.

I had always felt helpless when it came to my mother. Thinking about it, I’m sure that was part of why I was so easily frustrated and angry with the rest of my life.

“Richy?”

At first, because her voice was so small and soft, I didn’t realize my mother was awake.

I looked up and winced. She was in pain, but the tears in her eyes were not from her physical discomfort. It was from shame.

“Mom?”

“You shouldn’t be here,” she said, turning her head away. “I don’t want you to see me like this.”

I knew she didn’t want to hear it, but I said it anyway: “You can’t keep doing this to yourself, Mom. It’s going to kill you.”

Instead of getting angry—and I knew I deserved it for what I’d put her through—she turned away and buried her face in the pillow to hide the tears.

I sat there a few more minutes, not knowing what to say that wouldn’t make her feel worse.

To fill the silence, I said, “The nurse told me they were going to keep you here a while longer, just to make sure you’re going to be all right. Did you want me to get some things from home for you?”

Without turning her head back to me, she made a shooing gesture with her hand.

Her voice was weak. “I don’t care. Just leave me be.”

I saw her chest expand and contract quickly several times, and I realized she had started crying again.

I reached out, but before I could touch her, she said, “Please go. Just go.”

Feeling about as bad as I could, I stood, staring at the floor. “All right, I’m going, Mom. I’ll try to stop in tomorrow morning before work.”

She didn’t answer me, but I could hear her sobs long after I left the hospital.

Chapter Two

The rain fell

on the back of my head and neck like a thousand tiny needles. I hadn’t had time to grab a jacket when I left the house, and my thin shirt stuck to my shoulders and back, hugging my skin like plastic wrap. I was thoroughly soaked by the time I reached my mother’s car, fumbled for the keys, and got in.

After turning the ignition, I sat there, letting the car idle while I sorted out my thoughts.

I

was

trying to turn my life around, and do the right things. It seemed no matter how hard I tried, though, nothing made a difference. Maybe I had screwed up so bad in the past that my mother would never believe I had changed.

Or maybe she was so far gone in her alcoholism that there was nothing I could do to help her. I couldn’t accept that our relationship was so broken that it could never be fixed, but I didn’t have any idea how to go about it.

In the past six months since my release, I’d walked the straight and narrow. I went to work every day and did my job without complaint. I contributed a good portion of my pay to the household bills and the debts my mother had accumulated—mostly for my legal bills. I tried my best to follow the conditions of my parole, no matter how stupid some of them were. For example, I was forbidden from entering any residential property without written consent from the owner. Under that condition, I couldn’t have gotten a job delivering pizza if I’d wanted to. I was banned from any place that served alcohol, which meant I couldn’t wait tables in most restaurants. My options were limited.