Anonyponymous (6 page)

Authors: John Bemelmans Marciano

Old Lynch was just the kind of redneck you’d expect to be behind the Lynch law. But there was another Lynch, a Quaker by the name of Charles, who might have been the original judge. The Quaker Lynch was a justice of the peace and militia leader in Revolutionary War Virginia who was involved in rounding up and arresting a ring of British sympathizers supposedly planning a loyalist uprising. The Tory prisoners were given summary trials and dealt sentences that included hanging and were retroactively approved by the state legislature a couple of years later, perhaps sowing the perception that Lynch laws had inherent legitimacy.

So which Lynch was it? Recent research points to Charles, who is on record for using both the terms “Lynch’s law” (1782) and “lynching” in reference to himself. As for William, he wouldn’t be the first guy to stretch the truth; today it might have netted him a book deal and a guest shot on Oprah. And as for the 1780 pact he and his men made, this agreement—quoted and reprinted far and wide over the years—was likely a hoax perpetrated by Edgar Allan Poe, in whose

Southern Literary Messenger

it first appeared.

mal·a·prop·ism

n. An absurd masseuse of language

.

Mrs. Malaprop was a character in

The Rivals

, a comedy that debuted on the London stage in 1775 and was a long-lived hit across the English-speaking world. The actresses who played Mrs. Malaprop would elicit peals of laughter from the audience with lines such as “He is the very pineapple of politeness!” or “I am sorry to say, Sir Anthony, that my affluence over my niece is very small.” (People would kind of laugh at anything back then.) The author, Richard Sheridan, modeled the character’s surname on the French word

malapropos.

THE MILLINER’S TRADE

The top hat ushered in the modern era of men’s head wear with its introduction shortly before 1800. No man about town would go without one, but the problem was, they were so tall and unwieldy; what were you supposed to do with the hats once you took them off? With a few steel springs Frenchman Antoine Gibus rectified this problem, inventing the collapsible top hat, called an opera or crush hat, or a gibus.

William Coke II had a different solution: make the bloody thing shorter. Coke was sick and tired of all the goddamn tree branches knocking off his top hats when he took a horseback ride, so in 1850 he commissioned a more manageable and sturdier cap, which came to be known popularly as the bowler, after Thomas and William Bowler, the Southwark hatters who manufactured it. The name suited the hat and its bowllike shape, although the French, seeing a different silhouette, called it a

chapeau melon.

In the U.S. the bowler was instead known as a derby, supposedly because Americans became aware of the style from English dandies attending the Epsom Derby. The derby was the premier event in horse racing, so much so that the name came to mean “race” in a variety of contexts, from Kentucky to roller. Its origin dates to a 1779 coin toss, when Edward Smith-Stanley, the twelfth Earl of Derby, flipped Sir Charles Bunbury for the honor. (Rollerbunbury, anyone?) Although to this day a fashion must among women in the Andes, the bowler/ derby eventually yielded to softer hats with manipulat-able crowns and brims.

Fédora

debuted in 1882 with Sarah Bernhardt in the title role, a part written expressly for her by Victorien Sardou. Sardou and Bernhardt would work together many times, most famously in

La Tosca

(later adapted by Puccini), but it was the hat-wearing Princess Fédora Romanoff who set off a craze, as many a female fan of Bernhardt took to the streets sporting a fedora in a statement of both fashion and women’s liberation.

Similar to the fedora but with a narrower brim is the trilby, whose name also—bizarrely—derives from a play’s titular female character. The hat was worn in the first London production of

Trilby

, adapted from the hugely bestselling 1894 George Du Maurier novel of the same name. Set in bohemian 1850s Paris, the story follows the beautiful young artist’s model Trilby O’Ferrall as she falls under the control of the malicious, manipulative hypnotist Svengali. Normally, Trilby is tone-deaf, but under Svengali’s mesmeric spell, she becomes singing sensation La Svengali. It ends badly.

Baseball cap aside, the most American of headwear is the cowboy hat, aka the stetson, although upon its introduction John B. Stetson called his product “The Boss of the Plains.” Stetson recognized that a hat offering so much shade would provide welcome relief for the workingman out west. The stetson quickly became an indispensable part of the cowboy uniform and, in its ten-gallon variety, a symbol of Texas. If a man is “all hat and no cattle,” he’s wearing a stetson, even if only figuratively.

The need for shade on another frontier produced a different sort of hat. Improvised by British troops to keep the sun off their necks, the havelock is a cap with a hanging rear flap—think French Foreign Legion. The hat is named in homage to Major-General Sir Henry Havelock, who died of dysentery days after notching one of the most important British victories of the Indian Rebellion (a conflict previously known, when the winners named such things, as the Indian Mutiny).

Another military hat is the busby, by long-standing tradition said to be named after Dr. Richard Busby, a seventeenth-century headmaster so renowned for caning his charges that he appears in Alexander Pope’s

Dunciad

“Dropping with Infant’s blood.” Entering the lexicon as a “large bushy wig” (referring to the sadistic headmaster’s coif, perhaps?), the meaning of

busby

somehow switched reference to the tall and furry plumed hat of the much-copycatted Hungarian hussar.

Finally, there’s the tam-o’-shanter, worn by every bagpipe player you’ve ever seen, with the tartan pattern and the toorie on top. The classic Scottish bonnet is named after a 1790 poem by Robert Burns, known in Scotland simply as the Bard. (William who?) The brilliant Burns wrote in a mixture of English and Scots dialect, the latter evident in the title of his “Auld Lang Syne.” “Tam o’ Shanter” recounts the late-night drunken ride of its title character. “Inspiring bold John Barleycorn! What dangers thou canst make us scorn!” it goes, and as Tam nears the kirk, he happens upon a witches’ Sabbath. The party is in full swing, and Tam is particularly taken with the dancing of one scantily clad winsome witch: “[Tam] roars out, ‘Weel done, Cuttysark!’ And in an instant, all was dark.” The offended witches give chase, but just in time Tam’s horse, Meg, makes the Brig o’ Doon and the hellish legion vanishes, unable to cross the water.

(For those interested:

Tam

is a Scottish variant of Tom;

o’ Shanter

identifies his town of origin; a

toorie

is a pom-pom;

auld lang syne

means “old long since,” in the sense of “long ago”; a

kirk

is a church; “Weel done, Cutty-sark!” is akin to “Lookin’ good, Hotpants!,”

cutty

meaning short, as in cut off, and

sark

being Scots for shirt; and a

brig

is a bridge.)

mar·ti·net

n. A merciless disciplinarian; a stickler for rules

regardless of circumstance.

When Louis XIV ascended to the throne, French soldiery was a sorry lot. The ever-increasing importance of gunpowder-powered projectiles presented a particular challenge to the Gallic warrior, who exhibited a tendency to run the other way at the sound of it. The question was, How do you make men do something so stupid as hurl themselves headlong into a storm of cannon and musket balls? The answer: Bring on Jean Martinet, the original drill instructor.

King Louis made Martinet, who showed his mettle whipping the Régiment du Roi into shape, inspector general of the infantry in 1667, convinced that Martinet’s extreme brand of drilling would turn his soldiers into the mindless lemmings he desired. With draconian severity, Martinet instilled discipline and efficiency while demanding absolute adherence to even the pettiest of rules, paving the way for the future Sergeant Hulkas of the world and turning the French infantry into a well-oiled machine—no mean feat. For this achievement Martinet gained fame across the continent and the enduring contempt of his men.

Martinet would not live long. The drillmaster was killed during the siege of Duisburg, when he was shot down by the “friendly fire” of his own perfectly trained, well-disciplined troops.

A last note. In French a

martinet

is a swallow, but also a kind of whip, similar to a cat-o’-nine-tails and excellent for scourging. Until recently,

martinets

were available in pet-supply stores in France but have since been removed as they were being used mostly on children. They do, however, remain top sellers in S&M shops. Speaking of which, see next.

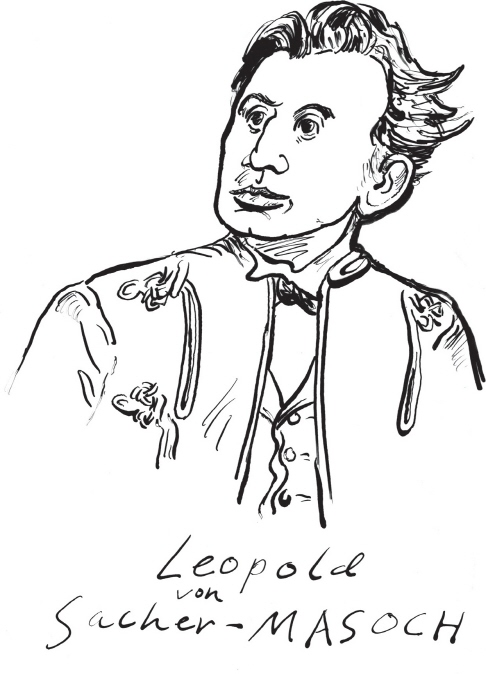

mas·och·ism

n. The urge to derive pleasure from abuse

and humiliation as administered by another or oneself, or

one’s sports team.

Leopold von Sacher-Masoch was a writer in Hapsburg Austria of the generation that preceded Freud and Klimt. His signature work was

Venus im Pelz (Venus in Furs)

, about a man who becomes obsessed with a woman named Wanda; the more he loves her, the more he wants to be degraded by her, to the point that he begs to become her legal slave. They sign a contract in which he promises to do whatever Wanda asks, with the singular condition that she always wear furs. Sadly for the hero, Wanda falls in love with another man who isn’t such a wuss.

Masoch’s book is definitively kinky, although by today’s standards (let alone those of his predecessor, de Sade) the sex scenes are demure, and the turgid prose is heavily weighted down by philosophical rambling. Masoch exalts himself as a “supersensualist,” identifying heavily with the Christian martyrs who gladly submitted to torture in return for elevated spirituality (see

tawdry

). The writer is at equal pains to explain his other fetish—a crazed obsession with furs—but does so rather less convincingly.

Venus im Pelz

was based on a real-life affair, and after its publication Masoch became involved with a woman named Aurore Rümelin, who played out certain of his fantasies, including taking on the name of his character Wanda. Masoch entered into a contract with this Wanda which began with the salutation “My Slave” and ended with, “Should you ever find my domination unendurable and should your chains ever become too heavy, you will be obliged to kill yourself, for I will never set you free.” The slave signed the document “Dr. Leopold, Knight of Sacher-Masoch.”

Masoch and Aurore/Wanda married, but somehow things didn’t work out.

mau·so·le·um

n. A large tomb, or a building containing

several of them, or a big empty place that feels likes one.

Mausolos was a Persian satrap who had a seriously nice tomb. In life, Mausolos expanded his family’s influence into Greece and came into conflict with Athens. Upon his death, in 353 B.C., the building of a great memorial in Helicarnassus was commissioned by Artemisia, who was doubly brokenhearted, being both Mausolos’ widow and sister. (Those satraps liked keeping it all in the family.)

The Mausoleum of Mausolos would go on to be named one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, the highest architectural prize pretty much ever. And for good reason. Not only was the tomb absurdly enormous, it was covered with statues and elaborate friezes carved by the finest Greek sculptors of the day.