Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder (26 page)

Read Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder Online

Authors: Nassim Nicholas Taleb

Enforcing consciousness of generalized iatrogenics is a tall order. The very notion of iatrogenics is quite absent from the discourse outside medicine (which, to repeat, has been a rather slow learner). But just as with the color blue, having a word for something helps spread awareness of it. We will push the idea of iatrogenics into political science, economics, urban planning, education, and more domains. Not one of the consultants and academics in these fields with whom I tried discussing it knew what I was talking about—or thought that they could possibly be the source of any damage. In fact, when you approach the players with such skepticism, they tend to say that you are “against scientific progress.”

But the concept can be found in some religious texts. The Koran mentions “those who are wrongful while thinking of themselves that they are righteous.”

To sum up, anything in which there is naive interventionism, nay, even just intervention, will have iatrogenics.

While we now have a word for causing harm while trying to help, we don’t have a designation for the opposite situation, that of someone who ends up helping while trying to cause harm. Just remember that attacking the antifragile will backfire. For instance, hackers make systems stronger. Or as in the case of Ayn Rand, obsessive and intense critics help a book spread.

Incompetence is double-sided. In the Mel Brooks movie

The Producers,

two New York theater fellows get in trouble by finding success instead of the intended failure. They had sold the same shares to multiple

investors in a Broadway play, reasoning that should the play fail, they would keep the excess funds—their scheme would not be discovered if the investors got no return on their money. The problem was that they tried so hard to have a bad play—called

Springtime for Hitler

—and they were so bad at it that it turned out to be a huge hit. Uninhibited by their common prejudices, they managed to produce interesting work. I also saw similar irony in trading: a fellow was so upset with his year-end bonus that he started making huge bets with his employer’s portfolio—and ended up making them considerable sums of money, more than if he had tried to do so on purpose.

Perhaps the idea behind capitalism is an inverse-iatrogenic effect, the unintended-but-not-so-unintended consequences: the system facilitates the conversion of selfish aims (or, to be correct, not necessarily benevolent ones) at the individual level into beneficial results for the collective.

Two areas have been particularly infected with absence of awareness of iatrogenics: socioeconomic life and (as we just saw in the story of Semmelweis) the human body, matters in which we have historically combined a low degree of competence with a high rate of intervention and a disrespect for spontaneous operation and healing—let alone growth and improvement.

As we saw in

Chapter 3

, there is a distinction between organisms (biological or nonbiological) and machines. People with an engineering-oriented mind will tend to look at everything around as an engineering problem. This is a very good thing in engineering, but when dealing with cats, it is a much better idea to hire veterinarians than circuits engineers—or even better, let your animal heal by itself.

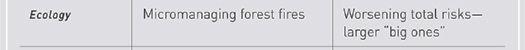

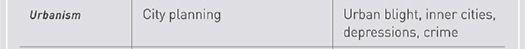

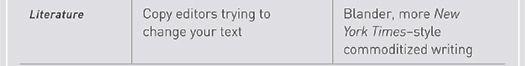

Table 3

provides a glimpse of these attempts to “improve matters” across domains and their effects. Note the obvious: in all cases they correspond to the denial of antifragility.