Archangel of Sedona (4 page)

Read Archangel of Sedona Online

Authors: Tony Peluso

“Of course, Sarge.”

“Tony, I’m putting you on the right ’cause I trust your ass.”

“Thanks, Sarge. I won’t fuck up. I’ll watch these guys,” I said.

“Watch your own ass, too. Nathaniel Victor has nothing to lose. He’d love to grease a nice Italian boy from New York before he buys the farm.”

“Sarge, I’m from Arizona. And we’ll be extra careful.”

“See that you are. Put Gallagher on the far right. He’s the best you got.”

“OK, Sarge. Will do.”

Once the company sweep began, I went into a super-vigilant mode. My fire team was headed for trouble.

I had to look out for two privates and a private first class. We’d be swinging east along the inside of the perimeter with a bunch of jumpy paratroopers on my right. Somewhere out in front, two or three experienced and committed North Vietnamese soldiers waited. Since it was past dawn, they’d missed their window. They knew that none of them would leave the base camp alive. They had nothing to lose.

We’d dispersed at the proper interval. I sent PFC Gallagher as a scout, a few more yards to the right. I had my head on a swivel, trying to ensure that we didn’t get jumped by the sappers or shot by our own guys.

Twenty minutes into the sweep, we entered an area where the engineers had been building an artillery battery emplacement. The construction crews had left two trucks, a bulldozer and Jeep. They’d parked the vehicles in a neat row from east to west, facing south. Something about the vehicles caused the hair on the back of my neck to go up.

I whistled. About 60 yards to the north, SSG Walsh heard me. I signaled that we had vehicles to our front. He alerted the platoon leader. The whole platoon slowed down.

Walsh signaled for me to take the fire team to the south side of the vehicles. The rest of the squad would be on the north.

“Listen up, guys.” I stage whispered. “The sappers might be hidden in and around those vehicles. There’s a fortified bunker manned by our troopers to the south. The rest of our squad will be on the north side of the trucks. We’ll be in the middle. Be fucking careful. There’s ten ways to screw this up. Get it right.”

As the fire team’s two privates swept past the first of the two-and-a-half ton trucks, I looked to the right and spotted an Airborne sergeant about 30 yards to the south. He stood behind a bunker next to the Green Line. He watched our movements with interest. I signaled him. He lowered his M-16 and nodded.

As I looked back out of the corner of my eye, I spotted an NVA sapper 20 yards to my left. He crouched underneath the first deuce-and-a-half. The two double sets of large rear wheels on each side had given him cover from my less-than-vigilant young troopers.

My men had walked right by him. If he’d had his AK 47 ready, he could have killed them both. Although it all took less than five seconds, I still remember what happened next in great detail.

The sapper had unscrewed the end of a Chicom grenade handle. He’d inserted a finger of his right hand into the small metal ring that connected a thin wire to the grenade’s fuse through the hollow handle. He prepared to toss the grenade at my men, which would disconnect the wire and arm the fuse. Four seconds later, it would explode. It could kill both of my men.

Though itchy-fingered Paratroopers surrounded me, I had to shoot the son-of-bitch. In less than a second, I brought my M-16 to my shoulder, flipping the selector to full auto. I fired a burst into the enemy soldier, hitting him at least three times.

The force of the impacts caused the sapper to snap backwards and involuntarily fling the grenade forward, arming it. Chicoms resemble the old German potato-masher hand grenade. Once they hit the ground, they bounce erratically. The sapper’s armed grenade bounced toward me, landing four yards away.

I yelled, “Grenade!” I dove to a prone position, trying to make myself as thin as possible. When the Chicom exploded, the concussion sucked the air from my lungs. Pieces of shrapnel slammed into my helmet, flak vest, load-carrying equipment, and my rifle.

I looked over at the sapper. He’d slumped to the ground. I could see his body writhing and blood spurting from his shoulder. A wave of fear swept over me, then a strange calm.

I started to check myself out. Gallagher got to me first.

“Tony, don’t move. Let me see where you’re hit. Stay still.”

“Get your ass back on that flank, PFC Gallagher!” I shouted. “They’re other sappers around. Watch your ass!”

SSG Walsh and the lieutenant came up after Gallagher got back in line, while I was still on the ground. They examined me, as my two negligent troopers secured the sapper, who was still alive.

“I’ll be damned,” SSG Walsh said.

“What?” The lieutenant asked.

“Giordano is the luckiest mother fucker in the Herd. He may have to change his underwear and get new LCE, but I don’t think he’s wounded at all.”

“Are you sure?” 2LT Andrews asked.

“Yes, sir. Let’s get him on his feet. He’s a little dazed by the blast, but he’s OK.”

“You sure got an angel on your shoulder, bud,” SSG Walsh said.

“I’ll say,” my platoon leader agreed. “No Purple Heart for you.”

“No confirmed kill, either,” Walsh said, as he looked at the wounded sapper.

“Sir, let’s get the medics over here. The sapper could have a ton of information about who else is lurking outside the perimeter.”

Less than 20 minutes after I shot the NVA soldier, the first platoon on our left encountered four sappers near a culvert that engineers had built across a small stream. Alerted by our earlier contact, our boys spotted the enemy before they could ambush anyone. After a brisk firefight, four NVA soldiers died. Two Americans received minor wounds.

The next day, at the express direction of my First Sergeant—a man that I still admire above almost all others—I held informal counseling sessions for my negligent subordinates behind the company shit house. Top supervised as I counseled each one in a dismounted Airborne bare-knuckle drill. The first session went well. The second proved far more challenging—but ended on the right note.

When it was all over, both of my men apologized and swore that they would never fuck up again. For the next several weeks, we became so close that one of the guys named his second son after me ten years later. The other, Tim Williams, died in my arms at LZ English. My oldest son bears his name.

I had several other close calls in Vietnam.

Six weeks after shooting the sapper, Tim Williams and I were in a C-123 transport that took ground fire on an approach into the landing strip at LZ English near Bong Son. Tracers from .51 caliber machine guns wounded Paratroopers in the webbed seats on both sides of me. One of the rounds hit Tim in the back and exited his chest. The enemy fire disabled the port engine and destroyed the hydraulic lines that controlled the landing gear.

Somehow, the brave and skilled aircrew managed to land the airframe, but other Paratroopers suffered serious injury in the controlled crash landing. Two of my friends, including Tim, died in that incident. After holding Tim until the life ebbed from his body, I walked away with a heavy heart, a ton of guilt, but without a scratch.

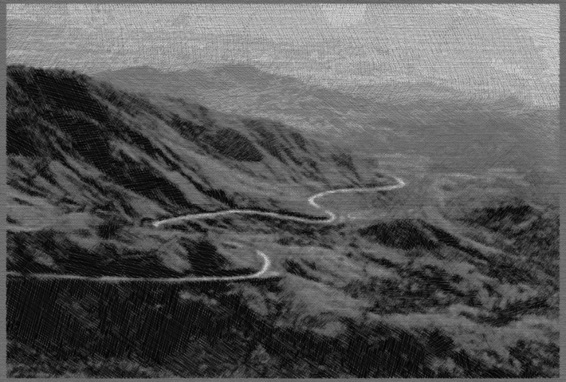

Two weeks later, on my 21st birthday in July, I rode shotgun on a Jeep that had business in Qui Nhon, a small Annamese town on the South China Sea. Due to the irresponsibility and gross misjudgment of a horny lieutenant, we missed our convoy back to An Khe in the Central Highlands. Adding insult to injury, the lieutenant ordered that we travel without an escort at dusk, west on Highway 19.

The driver, the officer, and I negotiated the treacherous switchbacks of the An Khe

Pass after dark. For the next hour, I could sense an evil presence along the road.

It wasn’t until the next day, when the NVA unleashed a massive ambush against a South Korean infantry battalion in An Khe Pass, that we realized that the NVA had followed our Jeep at every turn. Not wanting to spoil the tactical surprise or risk losing the bigger target, the enemy must have decided that three Americans were small potatoes. They let us through unmolested.

In addition to a dedicated, motivated, and deliberate enemy, threats at An Khe included drunken and deranged comrades.

The night that I made sergeant in November of 1968, an intoxicated, homicidal staff sergeant tried to shoot a close friend of mine over an imagined slur. After he fired his first shot at my buddy’s head, I attacked the senior man with my bare hands. I managed to disarm him as he fired all the rounds in his pistol’s magazine at the wall and ceiling. As he struggled to regain control of the pistol, two other new sergeants and I beat him savagely. Later, I could never explain how any of us survived.

In March of 1969, at the end of my self-extended tour of duty, I was the non-commissioned officer in charge of a detail in Saigon. It was supposed to be a boondoggle—an R&R disguised as an official mission.

On the last night of our sojourn, the NVA sent a barrage of 122 mm rockets into Saigon. One rocket hit our hotel in Cholon, destroying the fourth floor and setting the building on fire. My men and I remained on the 11th floor for several hours, trapped by the conflagration.

By all rights and every law of physics, the whole place should have burned to the ground. No fire department ever arrived to fight the flames. Miraculously, the fire burned out before it reached our floor. Americans died in the attack. Once again, I made it through unscathed.

I wasn’t blind. I could see how lucky I’d been. I wondered why I was the recipient of such good fortune. It wasn’t the guilt of the survivor. Something more profound was at work.

Becoming a Paratrooper and serving in Vietnam fulfilled a dream that I had since sixth grade, when I read a book about the Airborne that Sister Mary Assumption had purchased for our class library. The experience proved to be all that I’d hoped and feared it would be—and much, much more. The Army finished the job that the Jesuits started.

Chapter Three

May 3, 1999, 11:45 A.M

Major Crimes Section

Office of the United States Attorney

Tampa Division, Middle District of Florida

I wouldn’t trade my experiences as an enlisted man and non-commissioned officer for anything. Only my wife, sons, daughters, and grandchildren have more value.

In the three decades after the war, I had many successes and some dismal failures. After Vietnam, I married an Army nurse. We had two daughters. We put each other through college: grad school for her and law school for me.

In 1974, I returned to active duty in the Army as a Captain in the Judge Advocate General’s Corps. I’d found a way to reconcile my two treasured goals. My first assignment as an officer was with the 82nd Airborne Division. For the next few years, I jumped out of airplanes and tried criminal cases in courts-martial.

My extraordinary good fortune continued during my first tour at Bragg. In 1976, I survived a helicopter crash in an OH-58 Kiowa that had lost all power during takeoff.

As he was lifting from the Division Headquarters’ pad at the edge of the ridgeline overlooking Gruber Avenue, the pilot tried to auto-rotate the 100 feet to the ground. He had limited success. The helicopter crashed into a space between several stout pine trees, destroying the main rotor, fracturing the airframe, and catching on fire. Although the crew and I limped away, the pilot had compressed several vertebrae. He never flew again. Once again, my overworked guardian angel had kept me safe.

My first marriage did not survive Fort Bragg. After we broke up, I remained single for eight years. In the interim, I earned an advanced legal degree at George Washington University, served at the Army War College, did a second tour at Bragg, and taught Constitutional and Criminal Law at the Judge Advocate General’s School at the University of Virginia.

In 1984, I married a female officer in the JAG Corps. It took.

The Army assigned us to posts near Washington, D.C. In 1986, during the Iran-Contra Scandal, the Army posted me as the General Counsel of the White House Office of Emergency Operations. Almost everything about that job was classified. I can tell you that I had to travel a lot.

On a very snowy morning in January of 1987, I tried to drive from the District to a site in Western Virginia. I got as far as Gainesville on I-66. Five or six inches of snow and ice accumulated on the road, as the storm turned into a blizzard. The highway clearing crews had not gotten very far west by 0400 hours.

I had no traction in my powerful but very light 280ZX. I’d been stupid to even attempt the trip.

To make any headway at all, I fell in line behind an 18-wheeler traveling around 40 miles per hour. I set my front tires in the truck’s tracks, though my wheelbase was much narrower than his.

A half mile east of the exit for Gainesville, the big truck hit an ice patch and spun wildly to the right. As soon as I reached that patch, my little sports car began to do a full 360-degree rotation. No matter what I did, I could not gain purchase on the roadway.

When I got to the 180-degree point and faced east, another large truck bore down on me. Time slowed. The driver was doing everything that he could to avoid hitting me, but he had no control either.