Ariel: The Restored Edition (14 page)

Read Ariel: The Restored Edition Online

Authors: Sylvia Plath

APPENDIX I

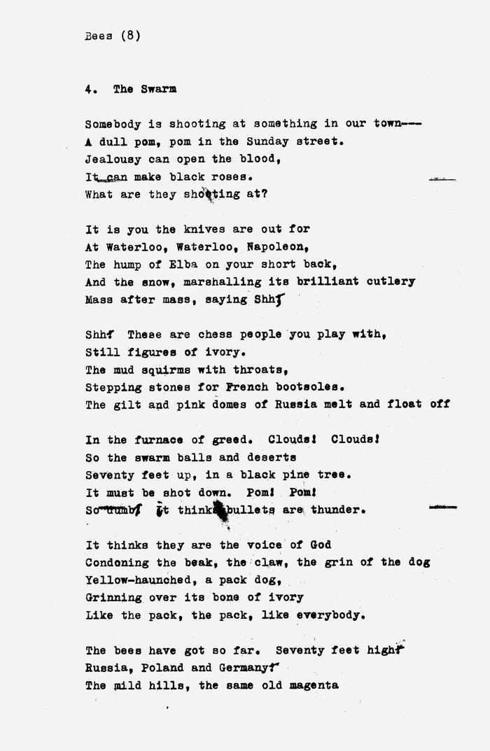

The bee poem ‘The Swarm’ appears on the contents page of the

Ariel and

other poems

manuscript with parentheses around it in Sylvia Plath’s own hand. She did not include the poem within the manuscript itself. Ted Hughes included it in the U.S. version of

Ariel

when it was first published in 1966. This restored edition maintains Sylvia Plath’s editorial decision and does not include the poem in the main body of

Ariel and

other poems

. The poem follows, along with a facsimile of a typescript draft.

Somebody is shooting at something in our town——

A dull pom, pom in the Sunday street.

Jealousy can open the blood,

It can make black roses.

What are they shooting at?

It is you the knives are out for

At Waterloo, Waterloo, Napoleon,

The hump of Elba on your short back,

And the snow, marshalling its brilliant cutlery

Mass after mass, saying Shh,

Shh. These are chess people you play with,

Still figures of ivory.

The mud squirms with throats,

Stepping stones for French bootsoles.

The gilt and pink domes of Russia melt and float off

In the furnace of greed. Clouds! Clouds!

So the swarm balls and deserts

Seventy feet up, in a black pine tree.

It must be shot down. Pom! Pom!

So dumb it thinks bullets are thunder.

It thinks they are the voice of God

Condoning the beak, the claw, the grin of the dog

Yellow-haunched, a pack dog,

Grinning over its bone of ivory

Like the pack, the pack, like everybody.

The bees have got so far. Seventy feet high.

Russia, Poland and Germany.

The mild hills, the same old magenta

Fields shrunk to a penny

Spun into a river, the river crossed.

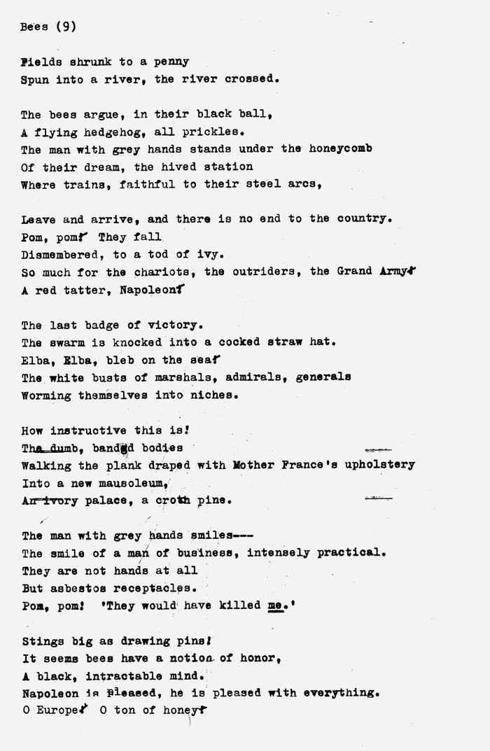

The bees argue, in their black ball,

A flying hedgehog, all prickles.

The man with grey hands stands under the honeycomb

Of their dream, the hived station

Where trains, faithful to their steel arcs,

Leave and arrive, and there is no end to the country.

Pom, pom. They fall

Dismembered, to a tod of ivy.

So much for the chariots, the outriders, the Grand Army.

A red tatter, Napoleon.

The last badge of victory.

The swarm is knocked into a cocked straw hat.

Elba, Elba, bleb on the sea.

The white busts of marshals, admirals, generals

Worming themselves into niches.

How instructive this is!

The dumb, banded bodies

Walking the plank draped with Mother France’s upholstery

Into a new mausoleum,

An ivory palace, a crotch pine.

The man with grey hands smiles——

The smile of a man of business, intensely practical.

They are not hands at all

But asbestos receptacles.

Pom, pom! ‘They would have killed me.’

Stings big as drawing pins!

It seems bees have a notion of honor,

A black, intractable mind.

Napoleon is pleased, he is pleased with everything.

O Europe. O ton of honey.

APPENDIX II

In a letter from December 14, 1962, later published in

Letters Home: Correspondence,

1950–1963

, Sylvia Plath wrote to her mother, Aurelia, that she ‘spent last night writing a long broadcast of all my new poems to submit to an interested man at the BBC’. The man referred to at the British Broadcasting Corporation was Douglas Cleverdon. The script that follows includes notes for ‘The Applicant’, ‘Lady Lazarus’, ‘Daddy’, ‘Sheep in Fog’ (which was not included in Sylvia Plath’s manuscript

Ariel and

other poems

), ‘Ariel’, ‘Death & Co.’, ‘Nick and the Candlestick’, and ‘Fever 103°.’

These new poems of mine have one thing in common. They were all written at about four in the morning—that still, blue, almost eternal hour before cockcrow, before the baby’s cry, before the glassy music of the milkman, settling his bottles. If they have anything else in common, perhaps it is that they are written for the ear, not the eye: they are poems written out loud.

In this poem, called ‘The Applicant’, the speaker is an executive, a sort of exacting super-salesman. He wants to be sure the applicant for his marvelous product really needs it and will treat it right.

This poem is called ‘Lady Lazarus’. The speaker is a woman who has the great and terrible gift of being reborn. The only trouble is, she has to die first. She is the phoenix, the libertarian spirit, what you will. She is also just a good, plain, very resourceful woman.

Here is a poem spoken by a girl with an Electra complex. Her father died while she thought he was God. Her case is complicated by the fact that her father was also a Nazi and her mother very possibly part Jewish. In the daughter the two strains marry and paralyze each other—she has to act out the awful little allegory once over before she is free of it.

In this next poem, the speaker’s horse is proceeding at a slow, cold walk down a hill of macadam to the stable at the bottom. It is December. It is foggy. In the fog there are sheep.

Another horseback riding poem, this one called ‘Ariel’, after a horse I’m especially fond of.

This poem—‘Death & Co.’—is about the double or schizophrenic nature of death—the marmoreal coldness of Blake’s death mask, say, hand in glove with the fearful softness of worms, water and the other katabolists. I imagine these two aspects of death as two men, two business friends, who have come to call.

In this poem, ‘Nick and the Candlestick’, a mother nurses her baby son by candlelight and finds in him a beauty which, while it may not ward off the world’s ill, does redeem her share of it.

This poem is about two kinds of fire—the fires of hell, which merely agonize, and the fires of heaven, which purify. During the poem, the first sort of fire suffers itself into the second. The poem is called ‘Fever 103°’.