Armageddon Averted: The Soviet Collapse, 1970-2000 (4 page)

Read Armageddon Averted: The Soviet Collapse, 1970-2000 Online

Authors: Stephen Kotkin

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Politics, #History

14a. Wide diameter pipes for siphoning off Russia’s wealth (they went to build a new gas pipeline, early 1980s). Under Brezhnev, Gosplan invested prodigiously in the gas industry, and after 1991

the gas monopoly, a state within the state, provided one-fifth of the Russian government’s budget revenues, despite highly dubious tax breaks and phenomenal

embezzlement by management, linked to the prime minister.

14b. Deadly toxins from nickel mining and smelting plants waft over the Arctic city of Norilsk, 1990s. The factories in Norilsk constitute the world’s single largest point source of sulfur dioxide emissions. They were built by Gulag (prison) labour and, after the Soviet dissolution, brought windfall export profits for management and then for new owners, a Moscow financial syndicate that concocted the infamous ‘loans for shares’ scam.

15a. T-72 tanks lined up for retreat. By fall 1994, from East Germany alone, the Russians withdrew more than 4,000 tanks, 1,300 planes and helicopters, 3,600 artillery pieces, 8,200 armored vehicles, and nearly 700,000 tons of ammunition (including nuclear-tipped shells), plus half a million soldiers and civilians (along the same corrider used by Napoleon during his infamous retreat in the opposite direction). Russia’s was the biggest pullout ever by an army not defeated in war.

15b. Main entrance, the Central Committee’s city within a city, 1991; a small crowd, concerned that evidence of party complicity in the August putsch was being destroyed, helped force the closure of the complex. Not long thereafter, the expansive CC site was reopened and again jammed with functionaries, having been rechristened the Presidential Administration.

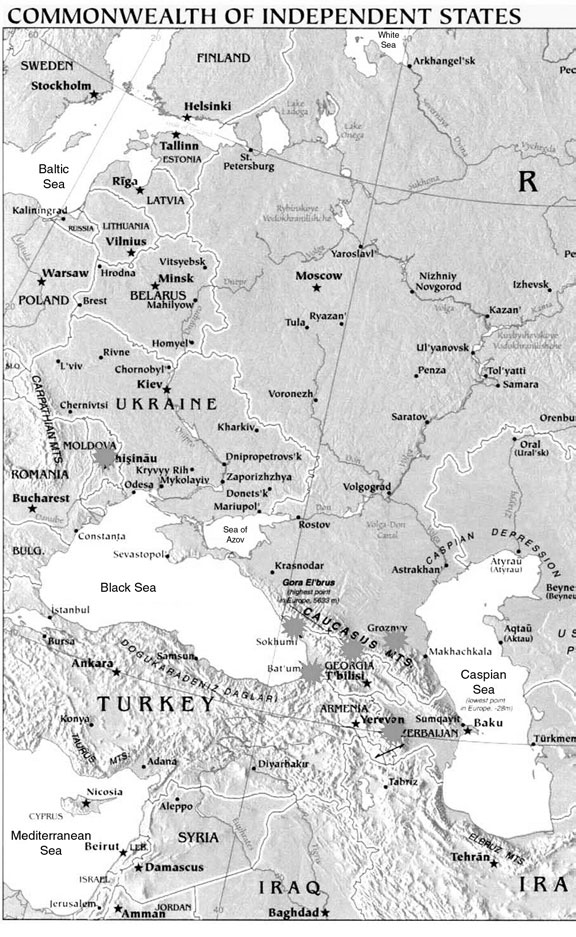

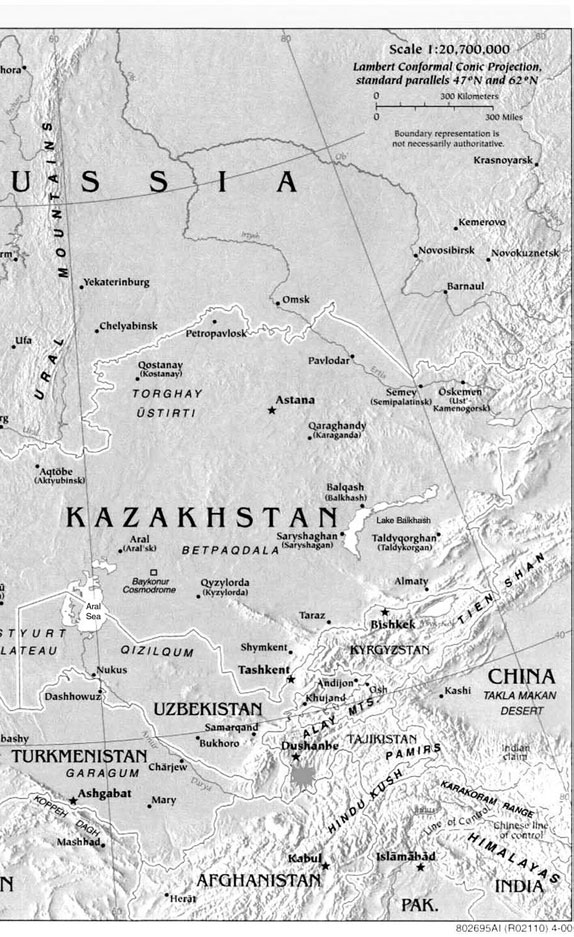

16. Summit meeting of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), which is neither a country nor a military alliance, nor a free trade zone, but a question mark.

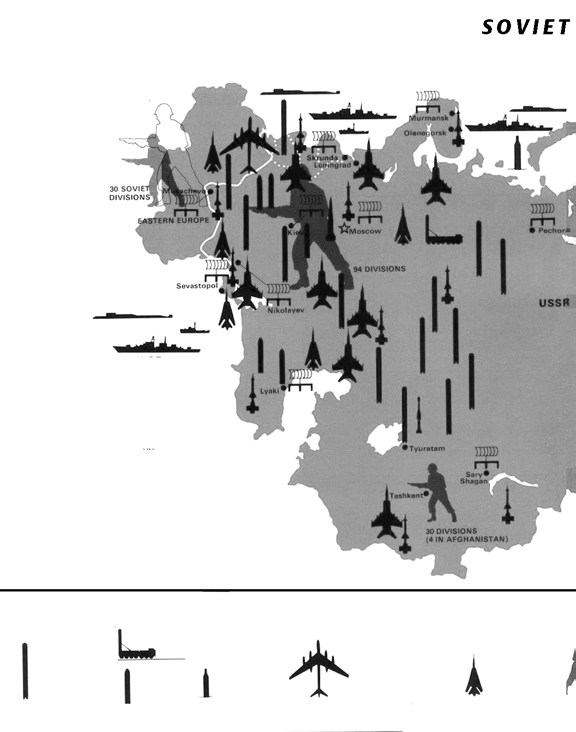

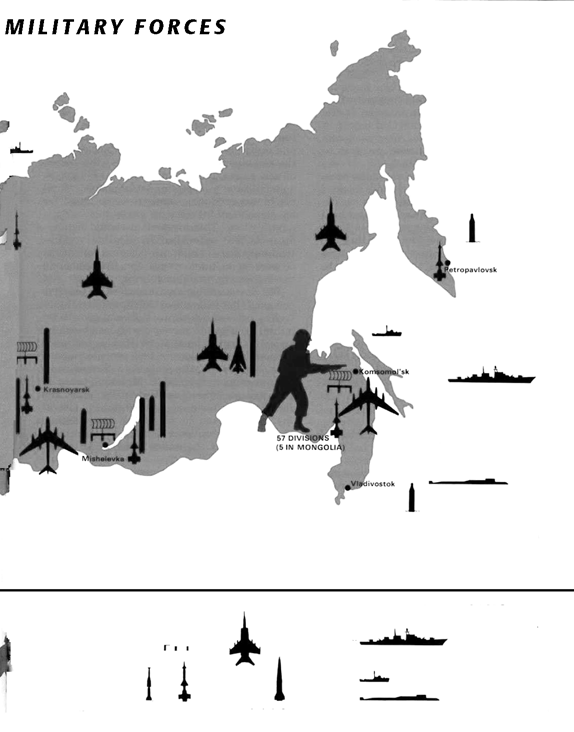

1 Pentagon depiction of Soviet capabilities xviii–xix

Soviet Military Power 1987 (US Government Printing Office)

2 Soviet and post-Soviet wars xx–xxi

Stephen Kotkin and Tyler Felgenhauer 3 World national income statistics 226–7

Dan Smith,

The State of the World Atlas

, 6th edn.

(Penguin)

4 Russia’s doomsday complex 228–9

Adapted from ‘Russia’s Nuclear Weapons Infrastructure’ in George Quester,

The Nuclear

Challenge in Russia and the New States of Eurasia

, crediting Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Washington, D.C.;

The Economist

25 Dec.

1993 – 7 Jan. 1994, 65; Ken Alibek with Stephen Handleman,

Biohazard

(Random House);

Washington Post

, 16 August 1998

5 Soviet and post-Soviet ecocide 230–1

Murray Feshbach and Alfred Friendly, Jr.,

Ecocide

(Aurum)

xix

1 Pentagon depiction of Soviet capabilities

2 Soviet and Post-Soviet Wars: Karabakh, Ajaria, Abkhazia, Ossetia, Ingushetia, Chechnhya (all in the Caucasus); Moldova (between Romania and Ukraine); Tajikistan (bordering Afghanistan).

This page intentionally left blank

Introduction

Reviewing the history of international relations in the modern era, which might be considered to extend from the middle of the seventeenth century to the present, I find it hard to think of any event more strange and startling, and at first glance more inexplicable, than the sudden and total disintegration and disappearance from the international scene . . . of the great power known successively as the Russian Empire and then the Soviet Union.

(George F. Kennan, 1995)

The problems that the Soviet leaders have to solve simply have no solutions . . . However, the Soviet leaders are not going to commit political suicide.

(Vladimir Bukovsky, 1989)

Virtually everyone seems to think the Soviet Union was collapsing before 1985. They are wrong. Most people also think the Soviet collapse ended in 1991. Wrong again. These points become readily apparent when one 1

examines the period 1970–2000 as an integrated whole, tracing the arc of Soviet economic and political institutions before and after 1991, and when one combines a view from deep inside the system with a sober sense of the precise role of the wider context. Forget about the dominant tropes of ‘neo-liberal reforms’ and ‘Western aid’ for describing post-Soviet Russia, let alone ‘emerging civil society’ for characterizing the late Soviet period. What happened in the Soviet Union, and continued in Russia, was the sudden onset, and then inescapable prolong-ation, of the death agony of an entire world comprising non-market economics and anti-liberal institutions.

The monumental second world collapse, in the face of a more powerful first world wielding the market and liberal institutions, was triggered not by military pressure but by Communist ideology. The KGB and to a lesser extent the CIA secretly reported that, beginning in the 1970s, the Soviet Union was overcome by malaise. But even though Soviet socialism had clearly lost the competition with the West, it was lethargically stable, and could have continued muddling on for quite some time. Or, it might have tried a Realpolitik retrenchment, cutting back on superpower ambitions, legalizing and then institutionalizing market economics to revive its fortunes, and holding tightly to central power by using political repression. Instead, the Soviet Union embarked on a quest to realize the dream of ‘socialism with a human face’.

This humanist vision of reform emerged in the post-Stalin years, under Nikita Khrushchev, and it stamped an 2

entire generation—a generation, led by Mikhail Gorbachev, that lamented the crushing of the 1968 Prague Spring, and that came to power in Moscow in 1985. They believed the planned economy could be reformed essentially without introducing full private property or market prices. They believed relaxing censorship would increase the population’s allegiance to socialism. They believed the Communist Party could be democratized. They were mistaken. Perestroika, unintentionally, destroyed the planned economy, the allegiance to Soviet socialism, and, in the end, the party, too. And the blow to the party unhinged the Union, which the party alone had held together.

That the man at the pinnacle of power in Moscow—a committed, true-believing Communist Party General Secretary—was engaged in a virtuoso, yet inadvertent liquidation of the Soviet system, made for high drama, which few appreciated for what it was. When crowds suddenly cracked the Berlin Wall in late 1989, and when Eastern Europe was allowed to break from the Soviet grip, dumbfounded analysts (myself included) began to wonder if the rest of the Kremlin’s empire, the Union republics, might also separate. That made the years 1990–1 a time of high drama, because, although it had been destabilized by romantic idealism, the Soviet system still commanded a larger and more powerful military and repressive apparatus than any state in history. It had more than enough nuclear weapons to destroy or blackmail the world, and a vast storehouse of chemical and biological 3