Armies of Heaven (42 page)

Authors: Jay Rubenstein

18

Jerusalem

(May 1099âJuly 1099)

Â

Â

Â

Â

E

nriched by 15,000 gold pieces from the amir of Tripoli, not to mention a fresh supply of horses, pack animals, and food, the crusaders were ready to abandon both Arqa and Tripoli for Jerusalem. The amir was happy to see them go. He even provided a guide, “an elderly man, since the paths through the mountains by the shore were convoluted and unmarked.” The army also decided, against custom but with the guide's help, to march at night.

nriched by 15,000 gold pieces from the amir of Tripoli, not to mention a fresh supply of horses, pack animals, and food, the crusaders were ready to abandon both Arqa and Tripoli for Jerusalem. The amir was happy to see them go. He even provided a guide, “an elderly man, since the paths through the mountains by the shore were convoluted and unmarked.” The army also decided, against custom but with the guide's help, to march at night.

They moved quickly. In the two days after leaving Tripoli, they covered over fifty miles to reach Beirut on May 19. Their goal was to reach Jerusalem before anyone in Egypt even knew that they had left Arqa. They also likely wanted to arrive in advance of any Greek expeditionary force, whose leaders might complain that Jerusalem had long ago belonged to the Greeks, having last been conquered by Heraclius in 629 AD, and that to the Greeks it should return.

1

1

The other Muslim cities that the Franks encountered along the way largely followed Tripoli's example, rushing the crusaders along before they could do any real damage, rather than trying to prevent them from reaching their destination. The citizens of Beirut offered them supplies on May 19, requesting only that the Franks respect the locals' property for as long as they camped nearby. The princes happily agreed.

The next day near Sidon, after another exhausting twenty-five-mile march, the Frankish camp became infested with poisonous snakes. Many

people were bitten; their limbs swelled up tremendously, their wounds bursting. Some died. The inhabitants of Sidon, after some brief resistance, decided not to fight but to give advice. The Franks should set men around the camp to beat on their shields throughout the night. This noise would keep the snakes at bay. As for the people who were sick, the locals recommended having the leaders place their right hands on the wounds. The touch of a crusading princeâlike the miraculous touch of French kings who were at that time curing their subjects of scrofulaâwould stop the flow of venom. If that didn't work, the ailing people should try having sex. Albert of Aachen, our source for this story, did not say how successful either of these remedies was.

2

people were bitten; their limbs swelled up tremendously, their wounds bursting. Some died. The inhabitants of Sidon, after some brief resistance, decided not to fight but to give advice. The Franks should set men around the camp to beat on their shields throughout the night. This noise would keep the snakes at bay. As for the people who were sick, the locals recommended having the leaders place their right hands on the wounds. The touch of a crusading princeâlike the miraculous touch of French kings who were at that time curing their subjects of scrofulaâwould stop the flow of venom. If that didn't work, the ailing people should try having sex. Albert of Aachen, our source for this story, did not say how successful either of these remedies was.

2

After a three-day rest, the Franks began another, two-day, fifty-mile march, this time camping outside the walls of Acre. Once again the local amir, fearful of a siege, offered the Franks terms, going so far as to promise Acre would become a tributary state of Jerusalem should the Franks capture the city. In the meantime he pledged them his friendship. It was a lie, as the Franks learned in miraculous fashion. While they were camping before Acre and scavenging for food, the bishop of Apt appreciatively watched a hawk in the sky pursue and kill a pigeon. The bishop ran to where the pigeon fell, somehow getting there before the hawk, and found attached to its body a note, written in Arabic lettersâthat the hawk, or rather God through the hawk, had delivered to the crusaders a carrier pigeon of the type Godfrey of Bouillon had seen a few months earlier during his negotiations with Omar of Azaz. The letter, as best the Franks could translate it, read, “The King of Acre to the Duke of Caesarea. A generation of dogs has passed me byâa stupid and violent people, without government, whom you and others should want to kill, as much as you love the law. And you can easily do it.” On another day the Franks might have made Acre pay for its amir's treachery and insults. For now they pretended to be friends. The pilgrims' beloved city awaited them. On June 3 she was within reach.

The Franks camped at Ramla, a mere thirty miles from Jerusalem. They took two more days to consider their strategy (a few independent voices at this stage, either from fear or simple pig-headedness, urged a last-second change of course and an attack on Egypt; they were ignored).

Then finally on June 6, the army set forth toward the destination which the soldiers had so long desired and of which they had so long dreamed.

Then finally on June 6, the army set forth toward the destination which the soldiers had so long desired and of which they had so long dreamed.

Â

The city of Jerusalem

Tancred couldn't wait. Throughout the crusade he had showed all of the ruthlessness, ambition, and independence of his uncle Bohemond, but by the time he was approaching Jerusalem, he had learned to combine these qualities with theological instincts that had always eluded his larger and more famous kinsman. As the rest of the army marched toward the village of Imwas, associated with the biblical town of Emmaus, where Christ had appeared to two of his disciples after death, Tancred, along with one hundred other knights, broke off and hurried instead toward Bethlehem.

The people at Bethlehem, hearing the sounds of charging horses in the early dawn, feared a Saracen attack. At the sight of Tancred, they rejoiced, picking up crosses and banners and starting a makeshift liturgical procession. Joyfully, they proclaimed, “You, our Christian brothers, are here to cast off our yoke of slavery, and to restore the holy places of Jerusalem, and to eliminate the rituals and impurities of the gentiles from that holy place.” Tancred accepted their gratitude and offered them his lordship.

Presumably, he and his knights then entered the Church of the Nativity to pray. Just to the side of the main altar, the Christians of Bethlehem would have shown him the entrance to a cave, allowing the Franks to descend into the earth to the stable where Christ was born, there to see and touch the grotto where he had lain and the spot where the ox and the ass had stood nearby. Arising from the sacred earth, Tancred turned to his men and ordered them to plant his banner atop the Church of the Nativity, “as if over the town hall.” It was an unseemly claim to own a churchâand what a church!âand the gesture would draw increasing criticism in the weeks to follow. But in that one action, Tancred managed to encompass all the piety, fervor, and raw greed that together defined the crusade princes.

3

3

From Bethlehem Tancred and his men rode quickly to the Holy City itself, arriving just a little ahead of the main army. With the walls and tow-ers

of Jerusalem in sight, still under the spell of Bethlehem's sacred history, Tancred dismounted, dropped to his knees, and sent kisses to the place for which he had so longed, his heart carried off to heaven. He ordered his men to set up camp near the gate at the Tower of David, but he rode alone toward the other side of Jerusalem, wanting to see for himself the places where Christ had lived and died.

of Jerusalem in sight, still under the spell of Bethlehem's sacred history, Tancred dismounted, dropped to his knees, and sent kisses to the place for which he had so longed, his heart carried off to heaven. He ordered his men to set up camp near the gate at the Tower of David, but he rode alone toward the other side of Jerusalem, wanting to see for himself the places where Christ had lived and died.

Â

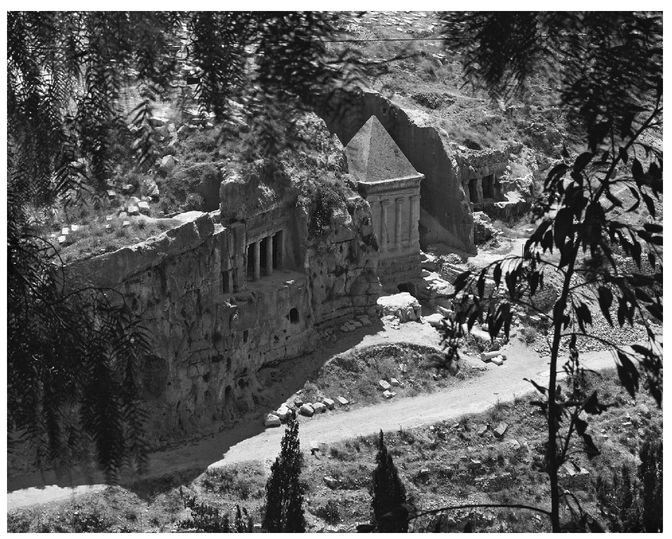

The tombs of the Kidron Valleyâone of the sites Tancred would have passed as he approached the Mount of Olives (Erich Lessing/Art Resource, NY)

The best views were to be found on the Mount of Olives. This was, perhaps coincidentally, the place prophecy indicated that the Last Emperor would make his presence known. The ride there would have been dangerous, the landscapes and monuments a little eerie, leading Tancred through the barren Hinnom Valley (known as

Gehnna

, the earthly incarnation of hell), past the ancient tombs in the Kidron Valley, past the garden of Gethsemane where Christ had prayed in agony as his apostles slept, and finally up the mountain to the site “where, Tancred had learned, the divine Christ had ascended to the Father.”

Gehnna

, the earthly incarnation of hell), past the ancient tombs in the Kidron Valley, past the garden of Gethsemane where Christ had prayed in agony as his apostles slept, and finally up the mountain to the site “where, Tancred had learned, the divine Christ had ascended to the Father.”

Tancred's description of what he saw, related years later to his biographer, retained a note of genuine wonder. “He was watching the people hurrying about, the armed towers, the soldiers making a din, men rushing to arms, young women bursting into tears, priests intent on prayers, calling them out with a shout, a scream, a noise, a shriek. He marveled at the temples, the ethereal dome of the Temple of the Lord, and the marvelous length of the Temple of Solomon, with the undulations of its grand portico: the whole place was like another city within the city.”

4

4

Whether Tancred went to the Mount of Olives primarily because of Scriptural association or because of a desire to gather tactical information, his visit soon took on a prophetic air. For as he surveyed the land and the city, and as his eyes drifted longingly from the Temple Mount to the dome over the Holy Sepulcher, a mysterious hermit stepped beside him. In the manner of a friend or a tour guide, he indicated to him, one by one, all of the important Christian sites in Jerusalem. The hermit also expressed surprise to see Tancred, a Christian, alone in such dangerous territory, but when he learned who Tancred was, descended from Robert Guiscard, Bohemond's father, “at whose threats all Greece trembled,” the situation became clear. “I will no longer marvel if you do marvelous things. Rather, I would wonder if you did not do marvelous things. Born from that family, it is not your lot to cleave to the path of ordinary men.”

As if to prove the accolade, five Saracen knights charged out of Jerusalem, through the Valley of Jehoshaphat, to attack Tancred, “believing him a spy”âwhich, presumably, he was. Tancred rode against them and killed three, forcing the other two into a shameful retreat. He then returned to camp at last, knowing himself to be the lord of Bethlehem and a figure of prophecy.

5

5

For the rest of the army, the final hours of the march were less eventful but almost unbearable. “Other nights had brought them bitter cold, or great fear, or battles; but this night was the hardest of all, because it kindled in their minds a desire long deferred.” At sunrise, at the mere mention of the city's name, “everyone poured forth floods of happy tears, because they were so close to the holy site of the city they longed for, on whose behalf they had suffered such hardship, such danger, and so many forms of death and hunger.” And when they actually saw the walls in the morning light, these few thousand pilgrimsâprobably about 20,000, just

under one-fifth of the soldiers who had originally left Europeâ“stood stock still, fell to their knees, and kissed the holy earth.” Some of them burst into song, loudly singing “hymns of praise, still weeping for joy.” Or as a poetic scribe entered into the margins of Robert the Monk's history, “Oh good King Christ, your people did weep how many a tear, when they saw that Jerusalem was near?”

6

under one-fifth of the soldiers who had originally left Europeâ“stood stock still, fell to their knees, and kissed the holy earth.” Some of them burst into song, loudly singing “hymns of praise, still weeping for joy.” Or as a poetic scribe entered into the margins of Robert the Monk's history, “Oh good King Christ, your people did weep how many a tear, when they saw that Jerusalem was near?”

6

The language of one contemporary historian, Guibert of Nogent, shifted here from battle narrative to something like spiritual adoration mixed with romantic desire. The whole army felt “a burning love of martyrdom.” Jerusalem was “their most intensely pleasurable destination, an enticement toward death and a lure toward wounds, to that place desired, I say, by so many thousands upon thousands.” All warfare involves an effort to correct a perceived wrong and in doing so to achieve a desire. But because of the intensity and complexity of the emotional associations with Jerusalem, these “affections” proved uniquely powerful. No group of aristocratic warriors had ever risked and suffered so much for the sake of spiritual gain alone. “This is my conclusion, and it is unprecedented.”

7

7

These thought processes sound similar to the modern, controversial psychological concept of “Jerusalem syndrome”: an overidentification with biblical characters experienced by visitors to Jerusalem that leaves them unable to distinguish between their world and Scripture. A similar sort of hallucinatory feeling captured the Franks as they finally achieved their goal. As one writer described it, the pilgrims wept the sweetest tears over Jesus, “and with the deepest affection they embraced Him, the cause of their daily labors and sufferings, as if He still hung there on the cross, as if He still lay shrouded in the tomb, through all space of remembered time.”

This derangement would prove dangerous during battle. According to Tancred's biographer, Ralph of Caen, at a later point in the siege some pilgrims lost control of their faculties altogether. As if with one mind, they charged the city's walls and embraced the stones like spouses, apparently thinking, “I will kiss my beloved Jerusalem before I die.” The city's defenders dropped rocks on the amorous pilgrims, killing them all, lost in their mad desires.

8

8

Other books

Wallflowers Don't Wilt by Raven McAllen

A Grimm Curse: A Grimm Tales Novella (Volume 3) by Janna Jennings, Erica Crouch

InsatiableNeed by Rosalie Stanton

Beyond: Our Future in Space by Chris Impey

Tempting His Mate by Savannah Stuart

Sons of Amber: Michael by Bianca D'Arc

Ace's Wild by Erika van Eck

Thrown By Love by Aares, Pamela

D.O.A. Extreme Horror Anthology by Burton, Jack; Hayes, David C.

The Atlantic Sky by Betty Beaty