Assassination: The Royal Family's 1000-Year Curse (32 page)

Read Assassination: The Royal Family's 1000-Year Curse Online

Authors: David Maislish

Tags: #Europe, #Biography & Autobiography, #Royalty, #Great Britain, #History

The execution of Charles I

The execution of Charles IThe people as a whole did not rejoice. It was the army that had demanded Charles’s execution. The royal grudge has lasted to this day; it is the Royal Navy, the Royal Air Force, the Royal Marines – but ‘the Army’.

THE INTERREGNUM

30 January 1649 – 29 May 1660

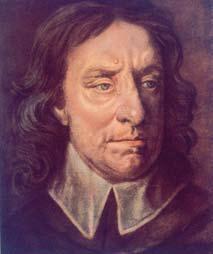

Not a king, but eventually a sovereign in all but name, Oliver Cromwell was born in Huntingdon in 1599. By a strange coincidence, Oliver’s mother’s maiden name was Steward, but she was no relation to the Stewards who became Stewarts and then Stuarts. Oliver’s father, Richard Cromwell, was a gentleman, the second son of a knight.

There may have been no relationship to the Stuarts through his mother, but Cromwell was related to the Tudors through his father. Owen Tudor’s son, Jasper Tudor (uncle of Henry VII), had an illegitimate daughter called Joan Tudor. She married William ap Yevan, and their son was Morgan ap Williams.

He was the Morgan Williams who married Katherine Cromwell, the sister of Henry VIII’s chief minister Thomas Cromwell; and Morgan and Katherine’s great-grandson was Oliver Cromwell. Seeing an easy advantage, Morgan and Katherine’s sons used their mother’s maiden surname of Cromwell. The family called themselves ‘Cromwell alias Williams’ in legal documents, as Oliver did in his marriage contract.

So, even if he did not know it, Oliver Cromwell was the 5 x great-grandson of Owen Tudor, as was Charles I. That made them sixth cousins.

Oliver went from a local school to nearby Cambridge University (a Puritan-controlled institution), although he had to leave when his father died. In time, his mother was able to send Oliver to London to study law at Lincoln’s Inn. While in London, Oliver met and later married Elizabeth, daughter of wealthy leather merchant and landowner Sir James Bourchier, after which they returned to live in Huntingdon.

In 1628, Cromwell was elected to Parliament as his father had been before him, but he made little impression. Everything changed when King Charles raised his standard in Nottingham. The 43-year-old Cromwell was one of the first to react. Within a week he had recruited a troop of horse in Huntingdon.

In the first major battle, at Edgehill, Prince Rupert (son of Prince-Elector Frederick and Charles’s sister Elizabeth Stuart) led the Royalist Army (‘the Cavaliers’); the Earl of Essex (son of Queen Elizabeth’s former favourite) led the Parliamentary forces (‘the Roundheads’). Cromwell’s cavalry played a small but successful role late in the battle. However, there was no victory, and Cromwell returned to London to enlist more men, enlarging his troop to a regiment. With that came promotion to Colonel.

Cromwell’s choice of personnel was revolutionary. He had seen the Royalist Army with its cavalry of young nobles, and he saw no hope in using rabble to fight them. So Cromwell concentrated on recruiting believers, men committed to the cause, led by officers with ability, appointed regardless of class. Soon he had a force of 2,000 disciplined men, and when they made their way through towns and villages, the sight of the trained and smartly-uniformed troops encouraged others to enlist. This was the origin of the New Model Army, full-time professional soldiers rather than part-time local militia.

At the next major battle, at Grantham, although heavily outnumbered, the charge of Cromwell’s horsemen (later to be named ‘the Ironsides’) secured victory, and it halted the Royalist Army’s march on London. Cromwell was thanked by Parliament, and he proceeded to win several minor engagements, always tactically superior to his opponents. He had learned from Prince Rupert’s mistake at Edgehill that when cavalry set men to flight, they should not charge after them for miles in the hope of easy slaughter, but should return to the main battle. It was the same mistake as had been made by the Anglo-Saxons (on foot) at Hastings and by Prince Edward at Lewes. Cromwell’s tactical genius was all the more remarkable because he had no military experience. He put it down to God’s will.

Cromwell was then sent north to serve under the Parliamentary commander, Lord Fairfax. He saw Cromwell at his best during an engagement at Winceby. Leading the cavalry charge, Cromwell’s horse was killed beneath him. Cromwell got to his feet, but was knocked to the ground; scrambling up again he found another horse and continued the assault. Fairfax led the second charge and secured victory.

Now Cromwell was Lieutenant-General and one of the Parliamentary leaders. His rise in both arenas was irresistible. The Battle of Marston Moor in 1644 saw a massive conflict, with the advantage going first one way and then the other. In the heat of the battle, Colonel Marcus Trevor, Commander of one of the Royalist regiments, spotted Cromwell and manoeuvred until he was almost alongside him. Riding as close as he could get to Cromwell, Trevor thrust his sword at Cromwell’s head and stabbed him in the neck. But the wound was minor; the attempt to kill Cromwell had failed. Nevertheless, Trevor

was rewarded when Charles II became king; he was created Viscount Dungannon.

Cromwell left the action to have his wound dressed. He quickly returned to the fray, and he led his cavalry in a charge that scattered Prince Rupert’s horsemen. Contrary to all practice, Cromwell held his men in formation, not allowing themtochasethefleeingRoyalists.Imposinghisirondiscipline, he ordered his men to turn and charge the other Royalist regiments, and a significant victory giving Parliament control of the North was secured. It was Cromwell’s secret: having cavalry that could make a second charge, in effect doubling the numbers under his command.

The Royalist Army re-formed, but Cromwell halted their advance with a series of successes. It was now decided that all officers who were members of parliament would leave the army and return to London. However, at Fairfax’s request and to the delight of the army, Cromwell was asked to continue as Lieutenant-General of the Horse at the Battle of Naseby.

Having superior numbers, the Parliamentary Army, with the benefit of Fairfax’s tactics and Cromwell’s genius, not just in leading the cavalry but also in directing the dragoons, gained a decisive victory. Once again, a vital element was Cromwell’s control of his horsemen, calling the majority back after routing the Royalist cavalry so that they could attack the Royalist infantry. As if to underline the difference, at the vital moment Prince Rupert and his cavalry were plundering the Parliamentary baggage train in continuation of a successful charge – they ended up two miles from the battle; when they returned, it was too late.

After the Second Civil War ended, Pride’s Purge gave control of Parliament to the Independents led by Cromwell.

The first task was to put Charles on trial. Every step Cromwell had taken in war and in Parliament had been successful, confirming to him that all he did was God’s will. The execution of the King was no different.

With the King dead, it was said that Cromwell ordered the head to be sewn back on so as to limit the horror suffered by any relatives viewing the corpse before burial. But this is not confirmed. If true, the favour would not be reciprocated; quite the opposite.

Next, the monarchy was abolished, followed two days later by the House of Lords. Then the Privy Council went, as did various courts, the Lord Chancellor, the Chancellor of the Exchequer and the Secretaries of State. All that was left was the House of Commons and the common law courts. Government was put in the hands of a council of 41 elected members. This was the new republic: the Commonwealth.

Two hostile groups faced the Commonwealth. The Levellers complained bitterly about the lack of social reform and the position of Cromwell as a quasi-monarch. More violent opposition came from Royalists in Ireland. Now Commanderin-Chief, Cromwell took an army to Ireland. Nine months of sieges and battles led to the bloody destruction of most of the Royalist strongholds, accompanied by massacres of Royalists and Catholics in towns that had refused to surrender. With Catholicism suppressed, more Protestant settlers were sent to Ireland. Cromwell was welcomed back to London as a hero.

It was time to deal with Scotland where King Charles’s oldest son, Charles, had landed and been proclaimed King. Taking his army north, Cromwell (now Lord-General) was faced with a problem: the Scots would not confront him in battle.

That did not make the situation safe. Cromwell advanced with a party of senior officers to reconnoitre near Coltbridge. They were spotted by a group of Scottish soldiers hiding in the undergrowth. One of the Scots stood up, raised his musket and fired at Cromwell, narrowly missing him. Cromwell shouted at the man, saying that if he had been under his command he would have had him cashiered for wasting a random shot from distance. The Scotsman shouted back that it had been no random shot; he had fought at Marston Moor and, having recognised Cromwell, he was taking the opportunity to kill him. With that, he ran off.

After some minor skirmishes, the Scottish Army moved forward, trapping Cromwell’s army at Dunbar. Having a two-to-one advantage, the Scots lay down to sleep, expecting victory in the morning. Early on 3rd September 1650, Cromwell attacked, and the Scots were routed in Cromwell’s most brilliant triumph.

Nearly a year later, while Cromwell was still in Scotland, Prince Charles marched at the head of a new Scottish army into England, advancing as far as Worcester. Many English supported him, but few would join an army of invading Scots. Cromwell followed with his troops, and was soon only 15 miles away. He held fast until it was to the hour exactly one year from his attack at Dunbar. A pincer movement led to an overwhelming victory: 2,000 killed and 9,000 taken prisoner for the loss of 200 men. Prince Charles hurried back to Paris, and Cromwell retired from the battlefield undefeated.

It was time for a fresh start. Treason in the past by word alone was forgiven, and penalties on Catholics were reduced. Although the Mass was still prohibited, it was no longer compulsory to attend Protestant services. However, there was little social reform and no change in the administration of justice other than abolition of the use of Latin.

Then a new problem arose: there was tension between the army and Parliament over the fact that an election was long overdue. After protracted argument, everything was agreed for a new election. The very next day, 100 members of parliament turned up at the Commons and voted on their own prolongation. When he was told, the deceived Cromwell stormed down to Westminster and addressed the House in fury at their treachery, ending, “You have been sat too long here for any good you have been doing. Depart I say, and let us have done with you. In the name of God, go!” He summoned soldiers, who removed the Speaker and cleared the chamber.

That was the end of the Rump Parliament (the rump that was left after Pride’s Purge) to general public satisfaction. A Council headed by Cromwell was established to govern the country until suitable arrangements had been made. The Council nominated 140 members for a new parliament from lists supplied by cities and counties. Within weeks, arguments about tithes (the tax payable to the Church) compelled Cromwell once more to send in the army and dissolve Parliament. This time, power passed to Cromwell.

He rejected the title of king, and agreed to be called Lord Protector; so the Commonwealth became the Protectorate. The position was to be elective, with a governing council and a new parliament in every third year.

The Protectorate produced a period of liberalism when compared to Puritan rule. Cromwell allowed dancing and theatre, even opera; literature flourished with Milton, Dryden, Lock, Isaak Walton and Marvel; and hunting and sport were encouraged. Cromwell himself smoked tobacco and drank alcohol, and he is said to have introduced port drinking to England. All a far cry from his stern reputation, although he did maintain the prohibition of Christmas festivities introduced by the Puritans who disliked their boisterous nature and the connection with Catholicism.

An example of Cromwell’s toleration was his attitude towards the Jews, Cromwell being only too aware of their contribution to the intellectual and economic prosperity of the Netherlands. When Cromwell’s secretary John Thurlow visited The Hague, he met with Manasseh ben Israel, a leader of the Jewish community, and, presumably on Cromwell’s instructions, advised Manasseh to apply to the English government seeking permission for the re-admission of Jews. Tolerant individuals and Puritans seeing an opportunity for conversion were in favour; merchants and most of the populace were against. The matter was argued in the Council and elsewhere, and in view of the opposition the matter was put aside. However, it was made clear that Jews already in England (mainly descendants of refugees from the Spanish Inquisition) were allowed to stay and follow their faith undisturbed, the Chief Justice having declared that the expulsion order of 1290 only applied to the Jews living in England in 1290. It was in effect an informal re-admission.

Toleration did not satisfy everyone. With one man holding so much power, assassination was always an option.

In early 1654, a group of Royalists plotted to assassinate Cromwell as he travelled to Hampton Court, a journey he made almost every Saturday with a troop of only thirty horsemen. After the assassination, the plan was for an army of 10,000 men led by Prince Rupert and James Duke of York (Charles I’s second son) to land in Sussex and proclaim Charles Stuart as king. The plot was discovered, and three of the principal conspirators, Peter Vowell, John Gerard and Summerset Fox, were seized and charged with treason. Vowell was hanged, and Gerard was beheaded. As he had confessed, Summerset Fox’s life was spared, he was transported to Barbados – it was the first time in English legal history that anyone had pleaded guilty to a charge of treason; it would only happen one more time.

Some of the Levellers also plotted assassination. A former Leveller officer, Edward Sexby (who had been court-martialled for executing a soldier and withholding his men’s pay), met in the Netherlands with another former Leveller soldier, Miles Sindercombe (who had fled after a failed mutiny), and they decided to murder Cromwell. They opposed his elevation to Lord Protector; they wanted a genuine republic.

Sexby would supply money and weapons, Sindercombe would gather more men and would carry out the assassination. Back in England, Sindercombe recruited renegade soldier John Cecil, petty criminal William Boyes and John Toope, who was one of Cromwell’s guards.

They decided to shoot Cromwell as he travelled through Westminster in his coach. Sindercombe rented a house in King Street, from which they would be able to see Cromwell’s coach as it went past. They quickly realised that it would be difficult for them to escape after the shooting, so they abandoned the plan.

Then they sought to shoot Cromwell with an arquebus as he left prayers in Westminster Abbey before the opening of Parliament. The arquebus was a lightweight predecessor of the rifle, capable of firing a shot that could pierce armour. On 17th September 1656, the conspirators met in the house of a Royalist, Colonel Mydhope, which was located next to the exit door of the Abbey. The first floor window would give a clear view of Cromwell as he left. Boyes was to do the shooting. He held the arquebus at the window, waiting for Cromwell to appear. As he waited, a large crowd gathered in the street below. The assassins would not be able to run through the crowd to get away. Boyes panicked, threw down the firearm and ran off.

Next, they decided to shoot Cromwell as he made his weekly journey to spend the weekend at Hampton Court. Sindercombe rented a house in Hammersmith from the coachman of the Earl of Salisbury. The house had a dining room that overlooked the narrow street along which Cromwell’s coach always passed, so narrow that the coach travelled at walking pace. Toope, as one of Cromwell’s guards, agreed to let Sindercombe know when Cromwell would be passing. All was prepared. Then, for some reason, Cromwell decided that on this occasion he would travel to Hampton Court by boat.

Still persisting, Sindercombe formulated a new plan. Cromwell often went for a walk in Hyde Park. So, the proposal was that Cecil would ride towards Cromwell, shoot him and then ride off. But as Cecil came near, Cromwell walked right up to him and complimented him on his horse. Cecil could not cope with the situation; he lost his nerve and galloped off, later telling Sindercombe that the horse had caught a chill and he would not have been able to ride away.

Finally, they decided to plant explosives in the chapel in Whitehall Palace where Cromwell often prayed. Toope helped them gain access, and they planted a device made of gunpowder, tar and pitch. Then Toope took fright and informed the authorities, and the explosives were removed. Boyes ran off, but Cecil and Sindercombe were caught. Sindercombe avoided a traitor’s death. A letter was delivered to him in prison, and the guards watched bemused as Sindercombe rubbed the letter on his hands and nose (or what was left of it after most had been cut off in the struggle when he was arrested); then he held his hands to his nose and mouth, inhaling and licking his fingers. The paper had been soaked in arsenic, and Sindercombe collapsed and died. Sexby was later arrested, but died of a fever before his trial.

Once more it was proposed that Cromwell should be crowned king. The Royalists were not altogether against the idea, at least it would re-establish the principle of monarchy; there would just be a contest between two families: the Cromwells and the Stuarts. Cromwell agonised on how to respond. After ten weeks of indecision, Cromwell said that he could not take the title of king, but he would be prepared to nominate his successor.

Now in his sixtieth year, Cromwell fell ill, probably malaria, possibly septicaemia. He struggled on, straining for an extra few days until he reached the anniversary of his famous victories at Dunbar and Worcester. Then, on 3rd September 1658, he died without nominating his successor.

Memories last for generations, statues of Cromwell being the main bone of contention. Queen Victoria refused to open the new Manchester Town Hall, because there was a statue of Cromwell outside. The Irish Nationalist Party forced Parliament to abandon a proposal to erect a statue of Cromwell in the House of Commons. Instead, it was erected outside Parliament, paid for by Prime Minister Lord Rosebery and his wife, Hannah de Rothschild.