At the Heart of the Universe (40 page)

Read At the Heart of the Universe Online

Authors: Samuel Shem,Samuel Shem

Tags: #China, #Changsha, #Hunan, #motherhood, #adoption, #Buddhism, #Sacred Mountains, #daughters

Afterward Xiao Lu takes Chun outside again to collect small branches and logs for the evening's fire. Again Xiao Lu watches as the woman trails along behind, helping a little. She is on alert, never letting them be alone, watching like a hawk, and always glancing back to make sure the man is all right. She seems very worried and very tense. Each moment with Chun is precious!

ïïï

Toward the end of the afternoon Chun asks if she can do more calligraphy.

Xiao Lu sits close to her at the table. Today she will teach her the eight basic brushstrokes that every Chinese child her age will already have learned.

Katie tries hard to follow her lead, surprised at how difficult the brush is to control, and amazed at Xiao Lu's skill. She's a good teacher, Katie thinks. She makes it fun and doesn't get impatient like her mom does, and she isn't in a hurry and doesn't seem to have something else on her mind.

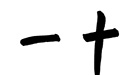

After a while the strokes are good enough, so Xiao Lu teaches her the classic stroke order for each character. As she describes the stroke, she motions to make Katie see what the word is. First horizontal, then vertical, like the character for “ten”:

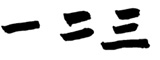

First above, then belowâlike the character for “three”:

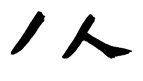

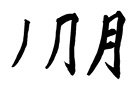

First to the left, then to the rightâlike the character for “man, person”:

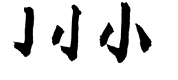

First in the middle, then on the sidesâlike the character for

“small”:

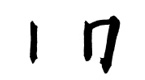

First outer, then innerâlike the character for

“moon”:

But if the outer stroke, like in the character for “sun,” forms a closed square, the lower stroke is written last. “First go in, then shut the door”:

Chun seems to really enjoy this, Xiao Lu thinks. Her head is bent low to the paper, the brush held upright, just as she has shown her. As she makes the characters, Xiao Lu giggles and applauds. Chun smiles at her. Xiao Lu feels a warm glow.

It's like when I was a child being taught by my own mother, and then by my dear teacher. By the time Xia was old enough to hold a brush, she had turned against me. I never taught her. Now I am teaching my own child.

Suddenly Xiao Lu realizes she has not yet shown her the most important character, the one for her name, Chun, “Spring.” She points to her, and says, “Chwin.”

“Chwin,” says Chun, pointing to herself.

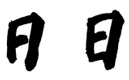

Xiao Lu smiles and nodsâthe accent is almost perfect. The woman is standing beside Chun now, looking over her shoulder. Xiao Lu catches the woman's eye, seeing that she is not happy at this. Why? It is her girl's name. She wonders how to show that Chun means “Spring.” She sits, puzzled. Then she realizes she can tell Chun the same story her first teacher told herâshe remembers the day like yesterday! She holds up three fingers to Chun and says in Chinese, “Three,” and draws the character for “three”:

Then she points to the character they just drew for “man, person,” and says it in Chinese and superimposes it on top of the “three”:

Finally she points to the character they've drawn for “sun,” and puts it below:

Over and over in gestures she paints a picture in the air above the character, pointing to each character as she makes it and saying to Chun: “Three. People. Sit. In. Sun.” She pauses. “Chwin. âSpring.'” She has Chun repeat each word, and corrects her intonation until she gets every syllable right. “Three people sit in sunââChwin, Spring.'” Finally Chun understands and says the whole sequence perfectly. It is her first sentence in Chinese and Xiao Lu claps her hands. Chun claps too, and turns and talks to the woman. The woman pretends to be excited. It is all Xiao Lu can do to keep from laughing at her clumsy effort.

Xiao Lu laughs and claps, says, “Chwin-Chwin,” and invites her to draw it. Carefullyâtoo carefully, so that it is chunky and out of proportion, she does. Xiao Lu takes her hand and guides her, over and over for ten “Chuns,” twenty, until she is starting to relax, and then another ten or twenty until, through her relaxation, it starts to be drawn, the character starts to come alive. She smiles and laughs and pats her on the head, and then she takes her by the hand and leads her over to a wall where some of her calligraphy scrolls hang. She points to the top character of one of themâit is a “Chun” much like the character she drew. Then she points out the top character of another “Chun,” but drawn with more freedom. She points out others, some so stylized that they barely resemble the first character she drew.