Austerity Britain, 1945–51 (43 page)

Read Austerity Britain, 1945–51 Online

Authors: David Kynaston

However, the Jew was about to be replaced by the black immigrant as the prime ‘other’. At the end of the war, some 20,000 to 30,000 non-whites were living in Britain, and studies were starting to be made of the attitude of whites towards them. Kenneth Little’s

Negroes in

Britain

– published in 1948 but mainly based on fieldwork done in the late 1930s and early 1940s in Cardiff’s Tiger Bay (where Shirley Bassey, seventh child of a Nigerian seaman, was growing up) – concluded hopefully that ‘a great deal of latent friendliness underlies the surface appearance of apathy and even of displayed prejudice in a large number of cases,’ though he did concede that it was difficult to generalise, given that as yet ‘relatively few English people have made close contact with coloured individuals.’ The other port with a sizeable number of black immigrants was Liverpool, where Anthony Richmond in the early 1950s examined what became of several hundred West Indians who went there during the war (under an officially sponsored scheme to boost production) and subsequently stayed on. Richmond found that by 1946 at the latest they were encountering considerable prejudice in the workplace from skilled tradesmen who, having served their apprenticeships, ‘resented being associated in the minds of English people with the unskilled negro labourer’: ‘Outside the field of employment there can be little doubt that the area of most intense prejudice against the West Indian Negroes is that of sexual relations,’ in that ‘men who are accepted in the ordinary course of acquaintance are subjected to serious insults if seen in the company of a white girl’, and ‘the girl herself is often stigmatised among all “respectable” people’.

A Guyanan at the sharp end of prejudice in 1947/8 was Eustace Braithwaite, who after demobilisation from the RAF struggled, for over a year and despite having a Cambridge physics degree, to get a job: ‘I tried everything – labour exchanges, employment agencies, newspaper ads – all with the same result. I even advertised myself mentioning my qualifications and the colour of my skin, but there were no takers. Then I tried applying for jobs without mentioning my colour, but when they saw me the reasons given for turning me down were all variations of the same theme: too black . . .’ Eventually, sitting one day beside the lake in St James’s Park and watching the ducks, he fell into conversation with ‘a thin, bespectacled old gentleman’ and related his plight. The stranger told him there were many vacancies for teachers in the East End, and soon afterwards Braithwaite secured a job at an LCC school in Cable Street, scene of the pitched battle between fascists and Communists in 1936. He was the only black teacher in London, and the eventual literary (and cinematic) upshot was

To Sir, With Love

.

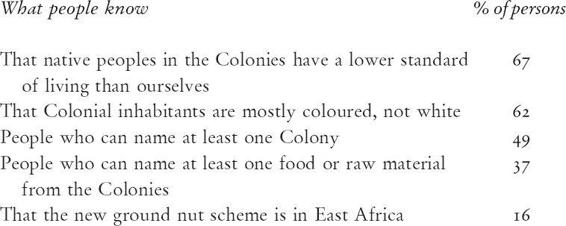

Ignorance about black immigrants and where they came from no doubt played its part in shaping indigenous attitudes. A survey of almost 2,000 adult civilians, conducted mainly in May 1948, revealed the following:

‘Housewives, unskilled operatives, and people over the age of sixty, are the least well-informed sections of the population,’ observed the report, adding that among even the most knowledgeable occupational group, comprising professional, managerial and higher clerical workers, less than two-thirds could explain the difference between a colony and a dominion. The report went on: ‘Public opinion is inclined to be complacent about the work that Britain has done in the Colonies. Only 19% think that we have “tended to be selfish in the past” – though this feeling is stronger among the better informed sections of the population than among the more ignorant. In any case, the great majority of people believe that we are doing “a better job now”.’

21

These were significant findings. Whatever people’s instinctive attitude towards black immigrants, not many believed that Britain morally owed them a favour. The guilt factor, in other words, was still the preserve of a privileged minority.

At the Ministry of Labour (MOL), faced by a serious labour shortage, the need to attract migrants was obvious. But whereas it went out of its way in these years to bring into the British labour market many thousands of white European workers, a high proportion of them Poles, its attitude to Caribbean labour was essentially negative, albeit sometimes covertly expressed. ‘Whatever may be the policy about British citizenship,’ Sir Harold Wiles, Deputy Permanent Under-Secretary, told a colleague in March 1948, ‘I do not think that any scheme for the importation of coloured colonials for permanent settlement here should be embarked upon without full understanding that this means that coloured element will be brought in for permanent absorption into our own population.’ The colleague, M. A. Bevan, agreed: ‘As regards the possible importation of West Indian labour, I suggest that we must dismiss the idea from the start.’ And in May, submitting a report on the question of employing ‘surplus male West Indians’, the MOL came up with an avalanche of reasons (or what it called ‘overwhelming difficulties’) why this was a bad idea. There was the major problem of accommodation; Caribbean workers would be ‘unsuitable for outdoor work in winter owing to their susceptibility to colds and the more serious chest and lung ailments’; those working underground in coal mines would find conditions ‘too hot’; and anyway, ‘many of the coloured men are unreliable and lazy, quarrels among them are not infrequent’.

22

That, it seemed, was that.

How did such attitudes chime with questions of British citizenship? The issue had been raised by Wiles in his March 1948 memo, in the knowledge that legislation was in the pipeline for what, following its second reading in May, became by the end of the summer the British Nationality Act 1948. This legislation, distinguishing between citizens of the United Kingdom and Colonies on the one hand and citizens of independent Commonwealth countries on the other, was essentially a response to Canada’s recent introduction of its own citizenship and sought to affirm, in the authoritative words of the historian Randall Hansen, ‘Britain’s place as head of a Commonwealth structure founded on the relationship between the UK and the Old Dominions’. It was not in any sense a measure centrally concerned with matters of immigration; and nor was it really about the colonies. Although in practice it sanctioned what over the next 14 years would be a very liberal immigration regime, it was (again to quote Hansen), ‘never intended to sanction a mass migration of new Commonwealth citizens to the United Kingdom’ – and, crucially, ‘nowhere in parliamentary debate, the Press, or private papers was the possibility that substantial numbers could exercise their right to reside permanently in the UK discussed’.

Significantly, with cross-party support and little public interest, the bill’s passage was smooth and quick. Inasmuch as politicians considered the immigration aspect, no one expected the legislation to have more than a marginal impact. The subsequent recollection of one Tory, Quintin Hogg – ‘We thought that there would be free trade in citizens, that people would come and go, and that there would not be much of an overall balance in one direction or the other’ – would have applied equally to Labour.

23

After all, the general expectation was that any future labour shortage could continue to be met by European labour; no one anticipated the increasing availability of cheap transportation from the Caribbean. The act was thus a fine example of liberalism at its most nominal. Yet by a delicious irony, even as the legislators legislated, that liberalism was starting to be tested.

On 24 May the

Empire Windrush

, a former German troop-carrier, set sail from Kingston, Jamaica, with 492 black males and one stowaway woman. Their destination was Tilbury, and as early as the 26th the London office of the Ministry of Labour reacted to the news with ‘considerable dismay’, predicting that if the men tried to get jobs in areas of worsening unemployment like Stepney and Camden Town (in both of which there were quite a few black workers already), ‘there will probably be trouble eventually’. By 8 June the minister, George Isaacs, was emphasising to MPs that the job-seekers had not been officially invited. ‘The arrival of these substantial numbers of men under no organised arrangement is bound to result in considerable difficulty and disappointment,’ he declared, adding, ‘I hope no encouragement will be given to others to follow their example.’ Over the next fortnight the MOL tried in vain to delay the

Empire Windrush

’s arrival but did arrange jobs for many of its passengers – mainly out of London and mainly well apart from each other.

Within the Cabinet the flak for this untoward turn of events was directed at the Colonial Secretary, Arthur Creech Jones. He was blamed on the 15th for not ‘having kept the lid on things’ and was requested, amid considerable press interest (curious rather than hostile) in the ship’s imminent arrival, to ‘ensure that further similar movements either from Jamaica or elsewhere in the colonial empire are detected and checked before they can reach such an embarrassing stage’. Replying to his critics three days later, Creech Jones did not deny that the men were fully entitled to come to Britain but sought to offer reassurance for the future: ‘I do not think that a similar mass movement will take place again because the transport is unlikely to be available, though we shall be faced with a steady trickle, which, however, can be dealt with without undue difficulty.’ Fewer than 500 constituting a ‘mass movement’? Given that over the previous 12 months as many as 51,000 white European voluntary workers had been placed in one sector alone of the British economy (agriculture), the subtext was almost palpable. Soon afterwards, in a letter sent to Attlee by 11 anxious Labour MPs, there was no beating about the bush:

This country may become an open reception centre for immigrants not selected in respect to health, education, training, character, customs and above all, whether assimilation is possible or not.

The British people fortunately enjoy a profound unity without uniformity in their way of life, and are blest by the absence of a colour racial problem. An influx of coloured people domiciled here is likely to impair the harmony, strength and cohesion of our public and social life and to cause discord and unhappiness among all concerned.

Accordingly, the MPs suggested that the government should, ‘by legislation if necessary, control immigration in the political, social, economic and fiscal interests of our people’. They added that ‘in our opinion such legislation or administration action would be almost universally approved by our people’.

24

This petition to Attlee was sent on Tuesday, 22 June – the very day that the

Empire Windrush

’s passengers disembarked at Tilbury. The

Star

’s report that evening concentrated on ‘25-year-old seamstress Averill Wanchove’:

She stowed away on the ship and was befriended by Nancy Cunard, heiress of the Cunard fortunes.

Tall and attractive Averill was discovered when the ship was seven days out from Kingston.

Mr Mortimer Martin made a whip round and raised £50, enough to pay Averill’s fare and to leave her £4 for pocket money.

Nancy Cunard, who was on her way back from Trinidad, took a fancy to Averill and intends looking after her.

Pathé newsreel film of the new arrivals featured the calypso singer Lord Kitchener (real name Aldwyn Roberts) performing his latest composition, ‘London Is the Place for Me’, a buoyantly optimistic number which he had started composing about four days before the boat landed. ‘The feeling I had to know that I’m going to touch the soil of the mother country, that was the feeling I had,’ he recalled almost half a century later. ‘How can I describe? It’s just a wonderful feeling. You know how it is when a child, you hear about your mother country, and you know that you’re going to touch the soil of the mother country, you know what feeling is that? And I can’t describe it. That’s why I compose the song.’

About half the men, presumably those without jobs already assigned to them, stayed temporarily at Clapham South’s wartime deep shelter, run by the LCC. On the first Saturday afternoon, the vicar of the Church of the Ascension, Balham, invited them to a service the next day, to be followed in the evening by tea in the hall. About 80 took up the offer. ‘The Jamaicans were charming people,’ the

Clapham

Observer

quoted W. H. Garland, a representative of the church, as saying afterwards. ‘They were churchmen and keen.’ The following Saturday – five days after some 40,000 mainly rain-soaked spectators at Villa Park had watched the middleweight Dick Turpin become Britain’s first black boxing champion – five of the shelter’s residents ‘introduced the “Calypso” to Clapham, when they played at the baths at a social held by the Clapham Communist Party’. Under the headline ‘Jamaicans Thrill Communists’, the local paper went on: ‘The chief exponent [Lord Kitchener?] of the calypso was called again and again to the microphone. Some of the verses he sang to the intriguing West Indian rhythm had been given before: others he made up as he went along, poking sly fun at members of the audience.’