Avengers of the New World: The Story of the Haitian Revolution (43 page)

Read Avengers of the New World: The Story of the Haitian Revolution Online

Authors: Laurent Dubois

perienced on earth: the annihilation of slavery in America”; “I hold it an

honor and always will,” he later wrote, “that I was the first to dare pro-

claim the Rights of Man in the new world.” But he also vehemently at-

tacked Louverture, claiming that he was a dangerous tyrant bent on con-

centrating all power in his hands, and portraying him as an enemy of

the Republic. “His unenlightened and superstitious mind,” Sonthonax de-

clared, “has made him dependent on counterrevolutionary priests who, in

Saint-Domingue as in France, are doing all they can to reverse liberty.”

Louverture was also, he claimed, under the influence of the returning

émigrés in their battle against emancipation.35

Louverture angrily denied such accusations. He had no problem with

the Republican administrators the French government sent to the colony,

just with the “strange Republican” Sonthonax. He reminded Laveaux of a

conversation they had once had, in which Louverture had argued that the

colony should be placed in the hands of “one European chief” who was a

“friend of general liberty” and who would be free from the “habits” and

“prejudices” of those from the colony. (Sonthonax had made the same

point in the middle of 1796, when he wrote to the colonial minister in Paris

that to manage the “liberty of the blacks” in such a way as to prevent the

population from becoming a “horde of savages” ungoverned by laws, it was

necessary for a “European to command in Saint-Domingue”; the point, of

course, sounded different coming from him.) He counterattacked with his

own accusation against Sonthonax: the commissioner had pushed him to

massacre the whites and “make the colony independent of the metropole.”

The commissioner had therefore become a threat to the “freedom of the

blacks.”36

Both Louverture and Sonthonax knew that most of the embittered and

often destitute exiled planters gathered in Jamaica, Philadelphia, and Paris

would never accept emancipation. By 1797 they were gathering strength

and attacking emancipation with increasing boldness. They were buoyed

by a larger wave of reaction in France, which in March of that year swept

many conservatives—including several Saint-Domingue planters—into of-

p o w e r

207

fice. By the time Louverture expelled Sonthonax, news of these changes

had come to Saint-Domingue. In fact, though neither of them could have

known it at the time, a month before Sonthonax’s expulsion, parliament

had demanded his recall. If Louverture’s accusations that Sonthonax advo-

cated independence were true, perhaps Sonthonax saw—prophetically, as

it turned out—that with such enemies consolidating their power in France,

in the end the only way to preserve the Rights of Man in Saint-Domingue

would be for the ex-slaves to proclaim independence. Louverture seems to

have used a different, more subtle, tactic. He offered up Sonthonax as a

sacrifice to liberty: by handing him over to the planters, he hoped to sate

them for a while.37

Louverture had ushered his longtime ally Laveaux, as well as Sonthonax,

off the stage. The last commissioner in the colony, Julien Raimond, former

advocate for the rights of the free coloreds, now deferred to Louverture’s

authority. The French officer François Kerverseau painted a portrait of

Louverture, relaxed and delighted, in the wake of Sonthonax’s departure.

“I saw the hero of the day,” he wrote; “he was radiant. His looks sparkled

with joy, his satisfied face announced confidence. His conversation was ani-

mated, no longer suspicious or reserved.” The black general was now un-

fettered by any other authority, free at last to shape the liberty of Saint-

Domingue on his own terms.38

208

av e n g e r s o f t h e n e w w o r l d

c h a p t e r t e n

Enemies of Liberty

Weconfronteddangersinordertogainourliberty,

and we will be able to confront death in order to keep it,”

warned Toussaint Louverture in a letter to the French govern-

ment late in 1797. Slaves had once “accepted their chains” because “they

had not experienced a state happier than that of slavery.” But those days

were over. The people of Saint-Domingue would rather, as Louverture

wrote in another letter, be “buried in the ruins of their country” than “suf-

fer the return of slavery.”1

In writing these words, Louverture was seeking to “conjure away the

storm” gathering across the Atlantic. The Saint-Domingue planters in Paris

were on the offensive. In May the planter Viennot de Vaublanc, a repre-

sentative in the newly elected Council of the Five Hundred, gave a strident

speech attacking emancipation. Saint-Domingue, he proclaimed, was in a

“shocking state of disorder” and under the control of a military government

run by “ignorant and gross negroes” who were “incapable of distinguish-

ing” liberty from “unrestrained license.” They had “abandoned agricul-

ture”; their “cry” was that the country belonged to them and whites were

no longer welcome there. The only solution was to force the ex-slaves to

return to the plantations where they had lived “before the revolution.”

Once there, they should be required to sign multiyear contracts. The ex-

cesses of emancipation had to be reigned in, argued Vaublanc, and the

population of ex-slaves coerced into serving as laborers for whites once

again. Other delegates made similar speeches. In June one proposed that a

large military force be sent to reestablish order in the colony, and that

the government pay for the return of all exiled planters. As they attacked

France’s colonial policy, Vaublanc and his partisans also attacked

Louverture, portraying him as a dangerous despot.2

Louverture wrote an impassioned response to Vaublanc’s speech. If the

ex-slaves of Saint-Domingue were ignorant, Louverture argued, it was for-

mer slave owners like Vaublanc who were to blame. Furthermore, lack of

education did not signify an incapacity for moral and political activity. “Are only civilized people capable of distinguishing between good and evil, of

having notions of charity and justice?” The “men of Saint-Domingue” had

little education, but they did not deserve to be “classed apart from the rest of mankind” and “confused with animals.”3

Louverture conceded that there had been “terrible crimes” committed

by ex-slaves in Saint-Domingue. But, he insisted, the violence in the colony

had been no greater than that in metropolitan France. Indeed, if the blacks

of Saint-Domingue were as “ignorant” and “gross” as Vaublanc proclaimed,

they should be excused for their actions. Could the same be said of the nu-

merous Frenchmen who, despite “the advantages of education and civiliza-

tion,” had committed horrific crimes during the Revolution? “If, because

some blacks have committed cruelties, it can be deduced that all blacks are

cruel, then it would be right to accuse of barbarity the European French

and all the nations of the world.” And if the treason and errors of some in

Saint-Domingue justified a return to the old order there, then was not the

same true in France? Would not it be justified to claim, on the basis of the

violence of the Revolution, that the French were “unworthy of liberty” and

“made only for slavery” and that they should be once more put under the

rule of kings? How, he further insisted, could Vaublanc gloss over “the out-

rages committed in cold blood by civilized men like himself” who had al-

lowed “the lure of gold to suppress the cry of their conscience”? “Will the

crimes of powerful men always be glorified?” “Less enlightened than citi-

zen Vaublanc,” Louverture concluded, “we know, nevertheless, that what-

ever their color, only one distinction must exist between men, that between

good and evil. When blacks, men of color, and whites are under the same

laws, they must be equally protected, and they must be equally repressed

when they deviate from them.”4

Instead of frightening the ex-slaves with the threat of a return to slavery,

Louverture suggested, white planters should accept and embrace freedom.

In so doing, they would assure themselves the “love and attachment” of the

ex-slaves. The blacks did not hate the whites, and in fact most of the ex-

slaves—including those on the half of the sugar plantations on the north-

210

av e n g e r s o f t h e n e w w o r l d

ern plain managed by whites—were dutifully working. They were not ene-

mies of order and prosperity. The planters who thirsted for a return to slav-

ery were. Louverture predicted that calls for limits on freedom, which

inevitably raised fears of a return to the old order, would set in motion a

self-fulfilling prophecy, creating the very defiance and rebellion they were

meant to destroy.

Moreover, he warned, any project to reestablish the old order would re-

quire a massive army, for the people of Saint-Domingue would have no

choice but to “defend the liberty that the constitution guarantees,” even

if it meant fighting France itself. Would not the French take up arms if

their freedom was threatened? What would the white planter Vaublanc do,

Louverture wondered, if he was, “in his turn, reduced to slavery”? “Would

he endure without complaint the insults, the miseries, the tortures, the

whippings? And if he had the good fortune to recover his liberty, would he

listen without shuddering to the howls of those who wished to tear it from

him?” Defending freedom, Louverture suggested, was a universal and in-

alienable right. And those who fought for it in Saint-Domingue would have

little choice but to win, or to die trying. Louverture reminded the French

government that there were maroons in the Blue Mountains of Jamaica

who had forced the English to grant them “natural rights.” He tactfully

avoided invoking events that would have been closer to home for French

readers, assuming they had not yet forgotten the insurrection of 1791. But

he was warning them not to start another war that they would lose.5

Julien Raimond similarly struck out against Vaublanc, arguing that his

speech was inflammatory and posed a serious threat to the prosperity of

Saint-Domingue. Raimond supported the policy of allowing exiled plant-

ers to return and rebuild their plantations, but he believed it was crucial

to prevent any men wanted to reestablish slavery entering the colony. In-

deed he argued that any whites who returned to Saint-Domingue should

have to take an oath never to “pronounce a single word in favor of slav-

ery.” Any attempt to restore the old system would, even if it was supported

by the French government, turn Saint-Domingue into a “mountain of

ashes.”6

Across the Atlantic, Louverture’s ally Etienne Laveaux was also follow-

ing developments in Paris with alarm. He had been unable to take up his

position in parliament, because the conservatives in Paris had annulled the

election in which he had been chosen. As he wrote to Louverture, he had

been dismayed to discover how powerful the enemies of emancipation had

e n e m i e s o f l i b e r t y

211

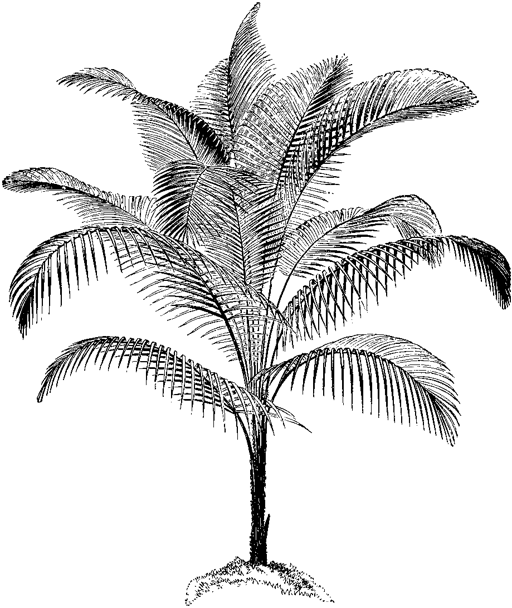

[To view this image, refer to

the print version of this title.]

“View of a Temple Erected by the Blacks to Commemorate Their Emancipation.”

From Marcus Rainsford,

A Historical Account of the Black Empire of Hayti

(1805). This monument, probably built under the rule of Louverture, recalled the emancipation of 1793–94. The tablet inside seems to list articles from the Declaration of the Rights of Man, which were often represented on tablets like these.

Courtesy of the William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan.

212

av e n g e r s o f t h e n e w w o r l d

become. “Men who drink not blood, but the sweat of men,” were trying to

have the decree of emancipation revoked and to “put the blacks back into

slavery.” He wrote that “all men who show themselves enemies of general

liberty” should be deported from the colony.7

In September 1797 there was a political about-face in Paris. A coup

d’état annulled the parliamentary elections that had brought Vaublanc and

other planters into office. Laveaux soon took up his post, along with several representatives of African descent elected alongside him. Along with other