B000U5KFIC EBOK (35 page)

Authors: Janet Lowe

In 1985, Munger and Buffett snatched Scott & Fetzer from the grasp

of hostile suitor Ivan Boesky for $315 million. Scott & Fetzer is the parent

of World Book Encyclopedia and Kirby vacuum cleaners.

In the second half of 1989, Berkshire cut three big deals that signaled

once and for all that Berkshire was a sophisticated contender in the world

of finance. A $1.3 billion investment was made in Gillette, USAir, and Champion International. Buffett and Munger negotiated together with

Gillette Chairman Coleman Mockler. In July 1989, Berkshire invested

$600 million in Gillette's preferred stock, all of which later was converted into common shares. Gillette has the sort of folksy history that appeals to both Munger and Buffett. It was founded in 1901 as the American

Safety Razor Co. by King C. Gillette. The company's first office was located over a fish market on the Boston waterfront. The company changed

its name to Gillette Safety Razor Co. in 1904. Gillette dominates the

worldwide market for razors with a 40 percent market share. In addition

to the razor blade business, Gillette owns Liquid Paper, Paper Mate and

Waterman pens, and Oral-B toothbrushes. In 1996 Gillette acquire Duracell batteries for $7.8 billion, the largest purchase Gillette ever made.

Gillette's earnings grew at an impressive 15.9 percent between

1985, but in the late 1990s it invested huge amounts of research and development funds in a new razor that sold well, but not quite as well as

hoped. Its earnings eventually slumped and Gillette's subsequent poor

stock performance was one contributor to a decline in Berkshire Hathaway's share price.

CONTRARY To WHAT SOME ANALYSTS CLAIM, Berkshire Hathaway is not a

closed-end fund. "No, it never was," said Munger. "We always preferred

operating companies to marketable securities. We used float to buy other

stocks. Berkshire has a lot of marketable securities-and big operating

companies. We like that system. We generate all this cash. We started out

that way, buying companies that throw off cash. Why should we change?"

Buffett had learned the basics of insurance when he was in graduate

school studying under Graham, who at the time was chairman of GEICO.

Buffett has used that expertise at Berkshire. Way back when Munger and

Buffett were acquiring Blue Chip Stamps shares, Berkshire made its first

substantial foray into insurance, purchasing National Indemnity Company in Omaha for approximately $8.6 million. Many of Berkshire's very

large investments are made through National Indemnity.

During this activity, Munger kept agitating to buy better quality companies, ones with strong earnings potential for the long-term and ones he

believed would be less troublesome to own.

"There are huge advantages for an individual to get into a position

where you make a few great investments and just sit back," said Munger.

"You're paying less to brokers. You're listening to less nonsense.... If it

works, the governmental tax system gives you an extra one, two, or three

percentage points per annum with compound effects."

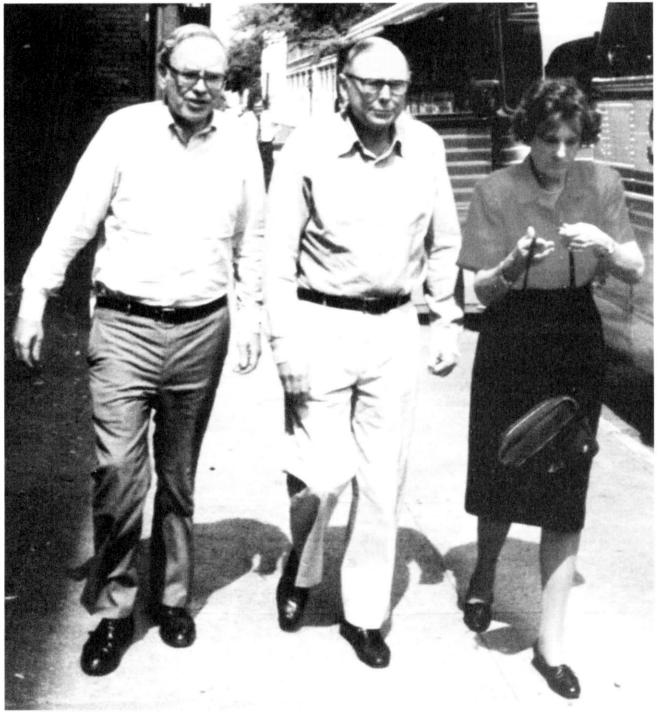

Warren Buffett, Charlie and Nancy Munger arrive at a Buffett Group gathering.

Starting with See's Candy, Munger nudged Buffett in the direction of

paying up for quality. "Charlie was very instrumental in pushing Warren

toward Coca Cola type investments-a franchise that will have carrying

value for generations," observed Ron Olson. "That is consistent with how

Charlie conducts his own life. He's not looking for a quick victory, but

to long-term success."

In 1988, Berkshire started acquiring Coca Cola stock, and within

about six months purchased 7 percent of the company. At an average

price of $5.46 a share, it was a total investment of $1.02 billion. Buffett, an addict of caffeinated soft drinks, felt confident that Coca Cola was a

quality company with superior long-term prospects. In fact, Buffett himself gave up Pepsi Cola in favor of Coke.-

"Many times, Charlie elevates Warren's thinking-such as going for a

stronger franchise. They can converse on any level," said Buffalo News

publisher Stan Lipsey. "When you have people that are thinking and living at that level, you not only get the intellectual exchange, you get ideas

that are complementary."

Apparently Munger hasn't always agreed with Buffett when it came

to personal investing, which at times worked to his advantage. When

Buffett sold Berkshire's Capital Cities Communications stock in 1978 to

1980, he later regretted the sale. Munger, however, kept some personal

holdings of Cap Cities, which performed exceptionally well'

Despite their blazing success, Buffett and Munger tried numerous

ideas that didn't pan out. Before they bought their Washington Post

shares, Buffett and Munger called on Katharine Graham and asked her to

participate in purchasing the Neu' Yorker magazine. Graham didn't even

know who these two guys from west of the Potomac River were, and she

didn't think twice before turning down their proposal.

"People used to bring projects in all the time. I just thought about

whether we wanted to be partners in the New Yorker. At the time I didn't.

I thought it needed a new editor and I didn't know how to choose one. I

sent them to see Fritz Beebe," said Graham.

The New Yorker was a lost opportunity, but probably not a huge loss.

Failures and misfires were part of the record during this period. "Some

major mistakes have been made during the decade, both in products and

personnel," Buffett wrote in Berkshire's 1977 annual report. Yet, he

added, "It's comforting to be in a business where some mistakes can

be made and yet quite satisfactory overall performance can be achieved.

In a sense, this is the opposite of our textile business where even very

good management probably can average only modest results. One of the

lessons your management has learned-and unfortunately, sometimes relearned-is the importance of being in businesses where tailwinds prevail rather than headwinds."9

Throughout the 1980s and straight through to the end of the century,

Buffett and Munger showed a knack for getting a good deal. When they

buy a company, the management usually stays with it and the acquisition

requires very little effort, except for collecting profits and allocating the

capital to its highest and best use.

"Our chief contribution to the businesses we acquire," said Munger,

"is what we don't do." What they don't do is interfere with effective managers, especially those with certain characteristics.")

"There's integrity, intelligence, experience, and dedication," said

Charlie. "That's what human enterprises need to run well. And we've been

very lucky in getting this marvelous group of associates to work with all

these years. It would be hard to do better, I think, than we've done."

Writing for an insurance publication, John Nauss, a Chartered Property and Casualty Underwriter, observed: "Warren and Charlie commented that they simply get out of the way and let their managers focus

on running their businesses without interference or concern about other

factors. But they do more. They create, perhaps, the best operating environment for businesses that exist anywhere. This environment includes

wise evaluations without extensive meetings and documents (we know

the business) as well as capital access, focused compensation, and freedom to do one's best." These methods, said Nauss, deserve greater attention from the business community."

BOTH CHARLIE AND WARREN SAY they set the example for Berkshire companies by keeping their own overhead costs at a minimum. Berkshires'

headquarters are simple and the staff is small. The company's overhead

ratio is !~s,,th that of many mutual funds.

"I don't know of anybody our size who has lower overhead than we

do," Munger said. "And we like it that way. Once a company starts getting

fancy," he said, "it's difficult to stop."

"In fact, Warren once considered buying a building on a distressed

basis for about a quarter of what it would have cost to duplicate. And

tempting as it was, he decided that it would give everybody bad ideas to

have surroundings so opulent. So we continue to run our insurance operations from very modest quarters."12

At one time Berkshire was subpoenaed for its "staff papers" in connection with one of its acquisitions, but, said Munger, "There were no

papers. There was no staff.""

But, as Munger so often says, what's right for Berkshire isn't necessarily right for all companies. "We've decentralized power in our operating businesses to a point just short of total abdication.... Our model's

not right for everybody, but it's suited us and the kind of people who've

joined us. But we don't have criticism for others-such as General Electric-who operate with plans, compare performance against plans, and

all that sort of thing. That's just not our style." He added, "Berkshire's assets have been lovingly put together so as not to require continuing intelligence at headquarters."

Berkshire Hathaway is one of the best-performing stocks in the history of the market. Its shares have underperformed the S&P in only five of the past 34 years, and book value has never had a declining year. An investor who put $10,000 into Berkshire shares in 1965 would have been

worth $51 million on December 1, 1998, versus a worth of $132,990 if

the money had been invested in the S&P. In 1999, PaineWebber insurance

analyst Alice Schroeder estimated Berkshire's intrinsic value at $92,253

per share. Using a more conservative approach, Seth Klarman of the

Baupost Fund estimated Berkshire to be worth between $62,000 to

$73,000 per share. At that time, the shares had retreated from their historic high in the $90,000 range, to around $65,600, and the price declined

even lower before recovering.

Shareholders are understandably loyal to a company with such a

record. Some families have invested with Buffett for two, three, and four

generations. Not only did Dr. Ed Davis and his wife benefit from Berkshire Hathaway, so did the Davis children and their families. Willa and

Lee Seemann have been with Berkshire since 1957. "People say the stock

is so high-I say yea, and it's going higher. The way to make money is to

get a damn good stock and stick with it," insisted Seemann.

JusT AS THE COLLECTION OF Berkshire holdings built over time, so has the

crowd at the annual meeting. "I remember when the attendance at the

Berkshire annual meeting was not much of anything," said Stan Lipsey.

"Warren said `we'll have a board meeting (actually, just a lunch), and said

come on up,"' and that was about it.

Otis Booth attended the meeting in 1970, when by happenstance he

was returning from the East Coast and Buffett suggested he stop in

Omaha. "There were only six or eight people present, Fred Stanback,

Guerin, Munger, and a few others. We all went out to dinner later," Booth

recalled.

Around 1990, Berkshire, Buffett, and to some extent Munger, began

developing a noticeable reputation. "I heard Charlie say for the first time

he was getting worried about adulators-movie star, rock star-type adulators. That was more than 10 years ago, when we met at the museum," said

Lipsey. At that same meeting, Lipsey got more of a glimpse into Munger's

character. "I had rented a normal-sized car, then I noticed Charlie had

rented a smaller one."

The number of people attending Berkshire's annual meeting grew

from 250 in 1985 to more than 11,000 in 1999. Most of Omaha gears up

for the Berkshire weekend. Gorat's, Buffett's favorite steak house, ordered

an extra 3,000 pounds of tenderloins and T-hones to feed the 1,500 people who were expected to dine there.14

In the audience at the Berkshire Hathaway meeting are apt to be

some impressive, though barely noticeable, people. Among them-former

FCC chairman Newton Minnow; Microsoft founder Bill Gates, and sometimes his father Bill Sr.; Disney's Michael Eisner; Abigail (Dear Abby) Van

Buren, and Chicago billionaire Lester Crown.15

The rise in attendance isn't entirely unwelcome. Buffett enjoys seeing the shareholders and goes out of his way to put on a good show. The

Berkshire Hathaway business meeting only lasts five to ten minutes, but

the question-and-answer period can last up to six hours, with as many as

80 questions posed by shareholders. At the meeting, it is Munger's designated role to play stoic straight man to Buffett's one-liners. Nevertheless it

was clear that Munger's influence on Berkshire continued to be strong. In

1997, Berkshire's Los Angeles lawyer Ron Olson was named to the Berkshire board.

Buffett and Munger hold court, dispensing corporate wisdom-and

as Charlie likes to remind people-facing the world as it really is. A

shareholder once complained that there were no great franchises like

Coca Cola left, meaning that Berkshire's style would be cramped in the

future. Munger replied, "Why should it be easy to do something that, if

done well two or three times, will make your family rich for life?"'6

Munger, like Buffett, is a fan of Berkshire-owned products. He drinks

Coca Cola, though not as much of it as Buffett does. Unlike Buffett, who is

a teetotaler, Munger doesn't mind substituting his Coke with an occasional beer or glass of wine. At the 1994 annual meeting, Munger put in a

plug for World Book Encyclopedias: