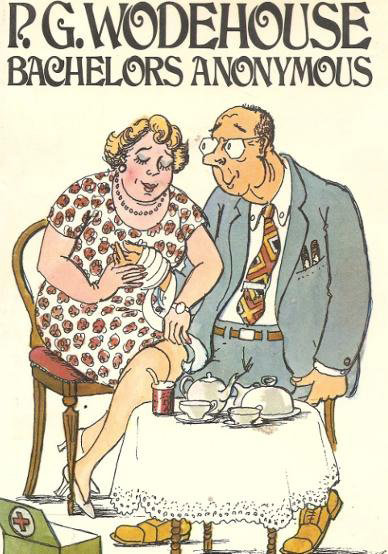

Bachelors Anonymous

Read Bachelors Anonymous Online

Authors: P.G. Wodehouse

P. G. WODEHOUSE

Bachelors Anonymous

Chapter One

Mr Ephraim Trout of Trout,

Wapshott and Edelstein, one of the many legal firms employed by Ivor Llewellyn,

head of the Superba-Llewellyn studio of Llewellyn City. Hollywood, was seeing

Mr Llewellyn off at the Los Angeles air port. The two men were friends of long

standing. Mr Trout had handled all Mr Llewellyn’s five divorces, including his

latest from Grayce, widow of Orlando Mulligan the Western star, and this formed

a bond. There is nothing like a good divorce for breaking down the barriers

between lawyer and client. It gives them something to talk about.

‘I

shall miss you, I.L.,’ Mr Trout was saying. ‘The old place won’t seem the same

without you. But I feel you are wise in transferring your activities to

London.’

Mr

Llewellyn felt the same. He had not taken this step without giving it

consideration. He was a man who, except when marrying, thought things over.

‘The

English end needs gingering up,’ he said. ‘A couple of sticks of dynamite under

the seat of their pants will do those dreamers all the good in the world.’

‘I was

not thinking so much,’ said Mr Trout, ‘of the benefits which will no doubt

accrue to the English end as of those which you yourself will derive from your

London visit.’

‘You

get a good steak in London.’

‘Nor

had I steaks in mind. I feel that now that you are free from the insidious

influence of Californian sunshine the urge to marry again will be diminished.

It is that perpetual sunshine that causes imprudence.’

At the

words ‘marry again’ Mr Llewellyn had. shuddered strongly, like a blancmange in

a high wind.

‘Don’t

talk to me about marrying again. I’ve kicked the habit.’

‘You

think you have.’

‘I’m

sure of it. Listen, you know Grayce.’

‘I do

indeed.’

‘And

you know what it was like being married to her. She treated me like one of

those things they have in Mexico, not tamales, something that sounds like

spoon.’

‘Peon?’

‘That’s

right. Insisted on us having a joint account. Made me go on a diet. You ever

eaten diet bread?’

Mr Trout

said he had not. He was a man so thin and meagre that a course of diet bread

might well have made him invisible.

‘Well,

don’t. It tastes like blotting-paper. My sufferings were awful. If it hadn’t

been for an excellent young woman named Miller, now Mrs Montrose Bodkin, who at

peril of her life sneaked me in an occasional bit of something I could get my

teeth into, I doubt if I’d have survived. And now that Grayce has got a divorce

I feel like a convict at San Quentin suddenly let out on parole after serving

ten years for busting banks.’

‘The

relief must be great.’

‘Colossal.

Well, would such a convict go and bust another bank the moment he got out?’

‘Not if

he were wise.

‘Well,

I’m wise.’

‘But

you’re weak, I.L.’

‘Weak?

Me? Ask the boys at the studio if I’m weak.’

‘Where

women are concerned, only where women are concerned.’

‘Oh,

women.’

‘You

will

propose to them. You are what I would call a compulsive proposer. It’s your

warm, generous nature, of course.’

‘That

and not knowing what to say to them after the first ten minutes. You can’t just

sit there.’

‘That

is why I welcome this opportunity of giving you a word of advice. You may have

asked yourself why I, though working in the heart of Hollywood for more than

twenty years, have never married.’

It had

not occurred to .Mr Llewellyn to ask himself this. Had he done so, he would

have replied to himself that the solution of the mystery was that his old

friend, though highly skilled in the practice of the law, was short on

fascination. Mr Trout, in addition to being thin, had that dried-up look which

so often comes to middle-aged lawyers. There was nothing dashing about him. He

might have appealed to the comfortable motherly type of woman, but these are

rare in Hollywood.

‘The

reason,’ said Mr Trout, ‘is that for many years I have belonged to a little

circle whose members have decided that the celibate life is best. We call

ourselves Bachelors Anonymous. It was Alcoholics Anonymous that gave the

founding fathers the idea. Our methods are frankly borrowed from theirs. When

one of us feels the urge to take a woman out to dinner becoming too strong for

him, he seeks out the other members of the circle and tells them of his

craving, and they reason with him. He pleads that just one dinner cannot do him

any harm, but they know what that one dinner can lead to. They point out the

inevitable results of that first downward step. Once yield to temptation, they

say, and dinner will be followed by further dinners, lunches for two and

tête-à-têtes in dimly lit boudoirs, until in morning coat and sponge-bag

trousers he stands cowering beside his bride at the altar rails, racked with

regret and remorse when it is too late. And gradually reason returns to its

throne. Calm succeeds turmoil, and the madness passes. He leaves the company of

his friends his old bachelor self again, resolved from now on to ignore scented

letters of invitation, to refuse to talk on the telephone and to duck down a

side street if he sees a female form approaching. Are you listening, I.L.?’

‘I’m

listening,’ said Mr Llewellyn. He was definitely impressed. Twenty years of

membership in Bachelors Anonymous had given Mr Trout a singular persuasiveness.

‘There

is unfortunately no London chapter of Bachelors Anonymous, or I would give you

a letter to them. What you must do on arrival is to engage the services of some

steady level-headed person in whom you can have confidence, who will take the

place of my own little group when you feel a proposal coming on. A good

lawyer, used to carrying out with discretion the commissions of clients, can

find you one. There is a firm in Bedford Row—Nichols, Erridge and Trubshaw,

with whom I have done a good deal of business over the years. I am sure they

will be able to supply someone who will be a help to you. It won’t be the same,

of course, as having the whole of Bachelors Anonymous working for you, but

better than nothing. And I do think you will need support. I spoke a moment ago

of the Californian sunshine and its disastrous effects, and I was congratulating

you on escaping from it, but the sun has been known to shine in England, so one

must be prepared. Nichols, Erridge and Trubshaw. Don’t forget.’

‘I

won’t,’ said Mr Llewellyn.

2

Leaving the air port, Mr

Trout returned to Hollywood, where he lunched at the Brown Derby, as was his

usual custom, his companions Fred Basset, Johnny Runcible and G. J. Flannery, all

chartered members of Bachelors Anonymous. Fred Basset, who was in real estate,

had done a profitable deal that morning, as had G. J. Flannery, who was an

authors’ agent, and there was an atmosphere of jollity at the table. Only Mr

Trout sat silent, staring at his corned beef hash in a distrait manner, his

thoughts elsewhere. It was behaviour bound to cause comment.

‘You’re

very quiet today, E.T.,’ said Fred Basset, and Mr Trout came to himself with a

start.

‘I’m

sorry, F.B.,’ he said. ‘I’m worried.’

‘That’s

bad. What about?’

‘I’ve

just been seeing Llewellyn off to London.’

‘Nothing

to worry you about that. He’ll probably get there all right.’

‘But

what happens when he does?’

‘If I

know him, he’ll have a big dinner.’

‘Alone?

With a business acquaintance? Or,’ said Mr Trout gravely, ‘with some female

companion?’

‘Egad!’

said Johnny Runcible.

‘Yes, I

see what you mean,’ said G. J. Flannery, and a thoughtful silence fell.

These

men were men who could face facts and draw conclusions. They knew that if

someone has had five wives, it is futile to pretend that he is immune to the

attractions of the other sex, and they saw with hideous clarity the perils

confronting Ivor Llewellyn. What had been a carefree lunch party became a tense

committee meeting. Brows were furrowed, lips tightened and eyes dark with

concern. It was as if they were seeing Ivor Llewellyn about to step heedlessly

into the Great Grimpen Mire which made Sherlock Holmes and Doctor Watson

shudder so much.

‘We

can’t be sure the worst will happen,’ said Fred Basset at length. A man who

peddles real estate always looks on the bright side. ‘It may be all right. We

must bear in mind that he has only just finished serving a long sentence as the

husband of Grayce Mulligan. Surely a man who has had an experience like that

will hesitate to put his head in the noose again.’

‘He

told me that when the subject of his re-marrying came up,’ said Mr Trout, ‘and

he seemed to mean it.’

‘If you

ask me,’ said G. J. Flannery, always inclined to take the pessimistic view, his

nature having been soured by association with authors, ‘it’s more likely to

work in just the opposite direction. After Grayce practically anyone will look

good to him, and he will fall an easy prey to the first siren that comes along.

Especially if he has had a drink or two. You know what he’s like when he has

had a couple.’

Brows

became more furrowed, lips tighter and eyes darker. There was a tendency to

reproach Mr Trout.

‘You

should have given him a word of warning, E.T.,’ said Fred Basset.

‘I gave

him several words of warning,’ said Mr Trout, stung. ‘I did more. I told him of

some lawyers I know in London who will be able to supply him with someone who

can to a certain extent take the place of Bachelors Anonymous.’

Fred

Basset shook his head. Though enthusiastic when describing a desirable property

to a prospective client, out of business hours he was a realist.

‘Can an

amateur take the place of Bachelors Anonymous?’

‘I

doubt it,’ said G. J. Flannery.

‘Me

too,’ said Johnny Runcible.

‘It

needs someone like you, E.T.,’ said Fred Basset, ‘someone accustomed to

marshalling arguments and pleading a case. I suppose you couldn’t go over to

London?’

‘Now

that’s an idea,’, said G. J. Flannery.

It was

one that had not occurred to Mr Trout, but, examining it, he saw its merits. A

hasty conversation at an air port could scarcely be expected to have a

permanent effect on a man of Ivor Llewellyn’s marrying tendencies, but if he were

to be in London, constantly at Ivor Llewellyn’s side, in a position to add

telling argument to telling argument, it would be very different. The thought

of playing on Ivor Llewellyn as on a stringed instrument had a great appeal for

him, and it so happened that business was slack at the moment and the affairs

of Trout, Wapshott and Edelstein could safely be left in the hands of his

partners. It was not as though they were in the middle of one of those

causes

célèbres

where the head of the firm has to be at the wheel every minute.

‘You’re

right, F.B.,’ he said. ‘Give me time to fix things up at the office, and I’ll

leave for London.’

‘You

couldn’t leave at once?’

‘I’m

afraid not.’

‘Then

let’s pray that you may not be too late.’

‘Yes,

let’s,’ said Johnny Runcible and G. J. Flannery.

3

Mr Llewellyn’s plane was

on its way. A complete absence of hijackers enabled it to reach New York,

whence another plane took him to London, where at a party given in his honour

by the Superba-Llewellyn branch of that city he made the acquaintance of a Miss

Vera Dalrymple, who was opening shortly in a comedy entitled

Cousin Angela

by

a young author of the name of Joseph Pickering.