Back of Beyond (14 page)

George shakes my shoulder.

“Said they’d be here round two. On the button, man.”

It is two-ten in the morning on a twenty-mile stretch of beach along the Caribbean shore of Costa Rica’s Tortuguero. Behind us, across the river, is the jungle, black and silent now, stretching back a hundred unbroken miles and more to the Nicaraguan border. Fifty yards in and you could lose yourself forever in that tangled chaos of vines and vegetation. Scary place.

“Counted four—an’ there’s more comin’.”

I peer out into the surf as it froths and skitters across the sand. Gradually black domed shapes, edged in moonlight, are wallowing up the beach.

They’ve arrived! Just like clockwork—some primordial pre-time clockwork—the green turtles of Tortuguero are coming home again to lay their eggs in the warm sand here as they have been doing every year for millions on millions of years. The eternal life-death-life cycle. And tonight we’re their only witnesses.

George is a native of this part of Costa Rica, one of Central America’s wildest regions. He’s seen it all before but seems as excited as I am.

“Just look at them!”

More are moving in now.

“This is going to be a night.”

George nods his grinning black face.

But we had no idea just what a night it would turn out to be….

Earlier in the day my monkey had moved me to introspection. Now it is the turtle’s turn. I’m fully awake. As they crawl laboriously up the long, moonlit beach I feel part of some eternal ritual, something that predates man’s appearance on earth by eons. A sensing of those ancient rhythms again.

“No flash, no lights,” warns George. “They git scared n’ go back.”

We don’t need them, the moon is full and everything is clear as daylight.

Slowly—unbelievably slowly—the great dome-backed creatures pull themselves up the sloping sand. One is enormous, almost five feet in length (“’bout eighty pounds a foot,” says George). She is only a few yards from our camp and has reached the nadir of the beach, near the sand-grass. Using her back flippers one at a time she begins to dig out her nest. We move closer slowly so as not to disturb her. Other turtles further down the slope see us and hesitate but the big one seems indifferent now, her eyes glazed and tearful.

“She cryin’. She’ll cry all the time till she finished. Keeps sand outa her eyes. An’ she don’t care ’bout us—she’s nestin’.”

As she digs deeper, well over a foot in now, her body becomes more steeply angled. Then she stops and just lies still, her eyes streaming. Suddenly her neck tightens, the leathery skin stretches like sinews and she opens her mouth wide. I expect a sound, she seems to be in pain, but nothing comes out except a gentle hiss. And then it happens. One by one, the tiny white eggs begin to drop into the sandy hollow. They’re like oversize golfballs glistening and leathery; you can see them dint a little as each one falls. Four or five and she pauses, lowering her head. Another straining heave and three more appear.

Within twenty minutes I count at least sixty eggs.

“Still got a ways to go,” says George. “She’ll drop ’bout a hundred. They comes back every two weeks ’bout three times—m’be five times, till they got no more left.”

George reaches out and pats her enormous shell but there’s no reaction from those crying eyes.

“Real gone.”

Before the coming of Archie Carr and the creation of the Tortugero National Park, the beach here, known locally as Turtle Bogue, was a gory killing field during the nesting season. Green turtles by the hundred were turned on their backs by

veladores

and were either slaughtered on the spot for their meat and gelatinous

calipee

(the essential ingredient of true turtle soup) or floated out to offshore boats with driftwood tied to their flippers. In addition, dozens of

hueveros

(egg stealers) and offshore

harponeros

(harpoonists) added to the carnage. By the 1950s the species was almost extinct.

“Was real bad,” George had told me. “Shells, bones—all the way up. Twenty miles. They didn’t even let ’em lay. If they did, they’d take all the eggs n’ sell ’em.”

Even Columbus himself noted the excellence of the turtles captured by his men when he explored this rich coast in 1502. Later, the eighteenth-century British Navy used these beaches regularly for supplies of turtles, which were kept alive for months in the holds of their ships.

We walk slowly across what seems like miles of beach. We’re a long way now from Archie Carr’s place and our kayuka (George’s canoe hacked out from a single tree trunk). The phosphorus in the surf is like a silver brush fire; the breeze is cool. The egg holes are filling. One smaller female (a mere two hundred pounds or so) has ended her laying and looks around as if emerging from some trance. She waves her back flippers and begins raking the sand over the eggs. She seems agitated and speeds up, using all four flippers at once; she lifts and drops her body on the sand to compact it.

“Sixty days there’ll be a hundred baby turtles runnin’ for the sea.”

George watches the mother.

“She’s gotta get back. Tide’s going out. S’long crawl.”

Slowly she turns to face the ocean. It’s hard to tell where her nest is now. She looks worn out, her flippers hardly move her at all. I feel like giving a push. Her route is erratic, zigzaggy tracks across the soft sand; she’s disoriented.

“Lights do that,” says George.

“What lights?”

He points up the beach. Those

are

lights. I thought they were fireflies.

“Who is it?” I’d expected to see more travelers here to witness this unique spectacle. Maybe that’s who they are.

“Veladores.”

“Poachers! You’ve got to be kidding. They stopped that years ago.”

George smiles.

“Are they armed?”

“They’ll have machetes. M’be more.”

“What have we got?”

He reaches under his loose T-shirt and slowly pulls out an eighteen-inch-long knife with a flat broad blade from a scabbard inside his trousers. We start walking toward the lights. At the top of the beach where the sand is harder we move faster. I can see a boat in the swell beyond the surf. There are two men ahead. They see us coming and turn their lights toward us. George raises his machete; sweat is dripping off his chin, his eyes are as hard as granite. They raise theirs and start toward us. This is starting to get a little frisky. George shouts and moves faster. They stop (thank God). There’s commotion, a lot of kicking sand; one of the men drops his light, then I see them scampering off down to the surf. George shouts again in the local dialect. The men keep running, tumbling into the waves, swimming to the boat. The motor roars, the men are dragged aboard, and it surges off through the choppy waves.

We reached the dropped lamp, pick it up and shine it across the beach. Ahead we can see at least six turtles on their backs. We expect the worst—turtles stripped of their valuable calipee and left to die. Luckily we’d come in time. The veladores had only turned them and possibly intended to float them alive to the boat for later dismemberment.

We stand looking at them, out of breath. We’ve got no energy left.

Righting overturned three-hundred-pound turtles is no easy matter. We work together grasping one flipper each, prying over the shell with our lower legs and leaping back out of the way of the four flailing flippers equipped with knife-edged claws that could quite easily slice off a finger. We watch the creatures crawl back down to the waves.

George strolls into the jungle behind the beach and brings back four small coconuts. He slashes the tops off with the machete and we pour the sweet liquid inside down our sand-raspy throats. We’re drenched in sweat; my head feels as light as a balloon. We lie down and sleep the sleep of the dead till dawn.

Come to think of it, I suppose the seventy-mile flight back to San José was quite an adventure, too, in a single-engine plane that rattled, bounced, and plummeted through another torrential thunderstorm with nil visibility all the way. Somehow we missed the ten-thousand-foot peaks of Volcan Barva and Volcan Irazú. The young pilot cringed with every metallic creak and kept fingering his rosary every time we lost radio contact with the airport. But I was obviously adventured-out and grinned like a baby all the way back. After all it’s not every day you’re given a chance to save a few endangered turtles with a friend like George.

GRAN CANARIA

Luck and I were on very amicable terms.

I couldn’t put a step wrong. Everything I did seemed to be turning out right. And what made it all so ironic was that a few days previously my situation, at best, had been desperate: funds at an all-time low, weather in southern Spain cold and lousy, ridiculously expensive ferries to North Africa, and border closings all along the North African coast, making a disaster out of plans for my journey. Oh yes. And some very old noises were coming out of my VW camper’s engine!

On the worst day of all I almost gave up and was about to dump the camper, hitch a ride to the airport and use up my return ticket home—home to wife and cats and warm baths. But I couldn’t. Go home early? What an admission of defeat. What a letdown. Crawling back like a drenched dog in the middle of January (and I was definitely drenched—it was the worst winter on record in Algeciras, that miserable little pimple of a place immediately to the west of Gibraltar, on the rump of Spain).

And then I saw them. Tanned as taco shells, in shorts and T-shirts, slim, fit, bright-eyed, giggling like kids at the muddy puddles, the rain-pummeled umbrellas, and miserable faces of the locals who were too depressed even to douse their sorrows in the ritual café-y-cognac tipples.

“Where the heck have you been?” I sounded like a drowning man crying out for rescue.

“The Canary Islands,” they said and smiled so happily that I hugged them, ran them out of the rain to a waterfront bar, and used up my day’s budget on cognacs for all of us, eliciting every detail and nuance about those magic isles that take poor, jaded, downtrodden, burnt-out cases from the gray climes of a North Europe winter and turn them into perky little paradise dwellers, who giggle at the rain and whose faces radiate pure sunshine.

Obviously I decided to go there. The next day.

For pennies I loaded my camper and me on board the enormous linerlike Canary Islands ferry. I looked forward to two days of oceanbound hedonism, feasting on tapas and splashing in the pool with all the pretty Spanish ladies. What I actually got was two days strapped to my bunk, foodless, as the ship lurched and plunged southward through Atlantic storms, to those remote volcanic blips off the Saharan coast of Africa. The only bonus: I finally read

War and Peace

, cover to cover, something I’d been promising myself since high school.

A few hours before arrival in Gran Canaria, the largest island of the seven Canaries, the storm ceased and we skimmed through mirror-glass waters, gleaming gold in a hot sun. Around six in the evening we saw the green and purple volcanoes of Gran Canaria rising out of the evening haze. Everyone congregated on deck and there was a communal silence, cathedral-like in its reverence.

Although referred to briefly by Pliny the Elder as the “Fortunate Isles,” little was known about these remote volcanic outposts until the arrival of Jean de Béthencourt in 1402, who came with plans for establishing embryo colonies for the Spanish crown. The randomly scattered Guanche and other Indians, the islands’ only inhabitants, were quickly rousted out of their cave-dwelling languor and eliminated long before Columbus’s brief but famous stopover here on the way to discover the New World.

Gran Canaria and Tenerife, whose 12,188-foot-high peak of Pico de Teide acts as a focal beacon for all the islands, experienced the first great surges of tourist-resort development in the 1960s. Little Lanzarote followed later and now boasts a handful of world-class beach resorts below that tiny island’s moonscape hinterland of still-active volcanoes, sinister lava fields, and “black deserts” of sand and ash. More remote and undiscovered are the tiny islets of Gomera and Hierro where dense rain forests and terraced mountains mingle with high sheep pastures (watched over by burly Castilian shepherds famous for their mountain-to-mountain “yodeling” language), towering volcanoes, and hidden lava-sand beaches—real earth-gypsy territory. Nobody could tell me much about them or the other two outer islands of La Palma and Fuerteventura. I planned to visit them all once I had gained my shore legs after a few days in Las Palmas. But things didn’t quite work out that way….

As we drew closer to Las Palmas harbor I heard music. Lots and lots of music. “Fiesta!” The word spread around the ship. Fiesta! Of course. It was New Year’s Eve. I’d lost track of the days in my fusty little cabin. It was celebration time and the capital city of Gran Canaria was full of people dancing, singing, shouting, waving crazy hats, letting off firecrackers. What a way to be welcomed!

I was one of the first off, scampering down the gangplank and sinking into soft sand (the sinking bit was involuntary; my legs didn’t adjust well to firm land at first). An enormous conga line of bodies snaked by, past the customs house, across the city park, and down through the narrow streets of pastel-colored houses to the main beach. I left my camper at the quay and joined in all the skipping and tripping like a lopsided lamb, losing myself in the frisky folk songs of the Canaries, laughing and hugging like everybody else, splashing myself with local rum from a leather

bota

flask, and finally collapsing in a sweaty heap on the soft sand, silvered by moonlight.

The beach was full of bodies—singing, kissing, dancing, and swimming in the slapping surf. Someone gave me a cigar “made in my island, senor, and may God be with you for the next year.” I offered all I had in return, some chocolate and nuts (meager remains of my oceanic staples), and I received more rum, a bottle of pungent red wine, half a pack of Gauloise cigarettes, three kisses, an invitation to breakfast, a bunch of grapes, another kiss, a song sung specially for me by a young man with a face like an angel, half a chorizo sausage, and still more Canary Island rum.

I danced again, joined in the choruses of those catchy local folksongs, swam, and finally as dawn began to creep up over the still ocean, curled up in the sand and slept the sleep of the gods for a few hours.

“Senor.”

Someone was touching my shoulder. I could feel the heat of the morning sun.

“Senor, some coffee.”

I woke up to find a tiny cup of espresso being pushed into my hand by a waiter from one of the beach-front cafés.

“You not dead, eh?” He was an elderly man dressed in a crisp white jacket. His wrinkled face spoke of vines and olive trees and years under the sun—and kindness.

“I see you sleep and I bring you something for wake up.”

I grinned a thank-you and swallowed the strong brew in two gulps.

“Ah—you forget.” He pointed to a glass of amber liquid on the tray. “Drink with coffee.” It was brandy, the strong Canary Island type, hardly distinguishable from the local rum and with the same kick. My first introduction to the ritual morning “café-y-cognac.” And it worked. I was suddenly wide awake, with a healthy flush on my cheeks. The old man was laughing.

“I think you like, eh?”

“I know I like,” I told him.

“Come to the café. One more is good for you.”

So I did, and it was. I left my bags with the old man and walked into the morning sea, surfless and still. There were bodies all over the beach, still sleeping. Someone was playing a timpale, the Canary version of the ukelele, with soft plunky notes that can be made to sound so sad when played close to the bridge and so alive when strummed in the rapid island manner, using thumb and all four fingers outstretched.

I lay back in the warm ocean and just floated, looking up at a cloudless gold-blue sky….

This was perfection. I had found my paradise. But it all seemed a little crazy. I had little in the way of cash. I hardly had enough to return the six hundred or so ocean miles to mainland Spain. I had no real idea why I’d come except for the warmth. I knew no one. I had no place to stay except for my faithful camper. I didn’t know how long I planned to stay or where to go next, and yet, the island spoke to me. Gently but firmly. “Stay,” it said. “Just stay and see what happens.” For a person who’s always on the move and loves to be on the move, it seemed an odd proposition. But the voice inside sounded so certain, so totally clear. “Stay. Stay and let things happen.”

And so that’s what I did. And that’s when I began to realize that luck and I were on very amicable terms. Once I allowed myself to let go, things literally arranged themselves, and I stood around watching like a delightful spectator as my life on Gran Canaria was fashioned gently before my eyes.

First a place to stay.

Well I obviously couldn’t afford the hotels, and I didn’t want to be near the crowded beach resorts and the winter tourists, many from the dark dank climes of Scandinavia, on a protracted two- or three-month winter sojourn. I wanted somewhere quiet, honest, basic. Somewhere near the ocean, hidden away. A place to think and paint and write….

My camper seemed to know where she was going. We left Las Palmas that afternoon in a rummy haze. The map of the island was open on the passenger seat but ignored. I let her just take the narrow island roads at whim. We climbed high up the slopes of the largest volcano, Valcequello, pausing in a pretty mountain village for tapas in a tiny blue-painted bar with a vine-shaded patio overlooking the whole island.

Here? I wondered. But we kept on moving.

More villages with lovely little churches and tiny plazas enclosed by neat white-and-lemon stucco buildings. Huge sprays of bougainvillea burst from roadside hedges. The scent of wild herbs rose from the tiny fields sloping down to the ocean. Banana plantations galore on terraced hillsides. Vast fields of tomatoes. Small vineyards. Cactus windbreakers protecting the huddled houses, white against the purpled green of the hills.

A tiny cottage with a stone roof appeared in a cleft between two church-high rocks. It had everything: vines, bananas, a small cornfield, two donkeys, two flagons of wine against a bright red door, blue shutters, and a view over cliffs and black volcanic soil beaches and ceaseless lines of surfing ocean.

Here? I wondered. But I still kept on moving and at dusk parked on a patch of grass below the volcanoes. Some bread, cheese, and chorizo sausage, a glass of brandy, and bed. I felt utterly at peace. Someone else was orchestrating this trip and that was just fine.

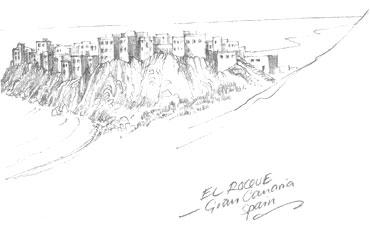

Very early the next morning it was all settled. I strolled away from the camper and sat on a rock, watching the sun come up. The black lava-crusted crest of Valcequello sparkled in the crimson-gold light. Then I looked down and saw something I’d not noticed the night before. A tiny white village, huddled, Greek island-fashion on top of a rocky promontory that jutted like an ocean liner straight out into the Atlantic. It was different from anything else I’d seen on the island. Most of the villages were straggly affairs, scattered over hillsides like blown confetti. But this place looked bright and strong and enduring on one-hundred-foot cliffs. A long flight of steps climbed up to it from a track. There was no road through the village, just a sinewy path with Cubist houses packed together on either side and ending in an area of level rock at the end of the promontory. I could see laundry blowing in the morning breezes; the hillsides below rose steeply from the rocky beach and were smothered in banana trees. It looked completely cut off from the rest of the island. A true hidden haven. Mine!

Somehow the camper groped her way down from the volcano, bouncing and wriggling on cart tracks cut through the brush. It was wild here. Not at all like the softer eastern side where the tourists congregated. I saw no one around as we descended. But my camper knew where she was going and I was happy to play along.

Around midmorning I arrived. The village looked even more dramatic close up. Scores of white-painted steps rose up the rock to the houses that peered down from their cliff edge niches. Some children were playing in the dust at the base of the steps. They stopped and slowly approached, smiling shyly. A rough hand-painted sign nailed to a tree read

El Roque

.

“Ola!”

The children grinned. “Si, si, Ola. Ola!”