Back of Beyond (20 page)

“We have to go west, to the coast,” Ali finally decides. “There is no other way.”

Fatima and the girls, who seem to have come through the chaos safely, nod sadly. Their plans for teaching the ancient Saharan dances to nomads at the oases to the south will have to be abandoned. The others also begin to calculate their enormous losses, their rugs, their silver daggers, their boxes of Berber jewelry…. We are becoming a thoroughly miserable lot until Saiid leaps up and begins shouting:

“This is stupid. We should be thanking Allah for our lives. We are alive! They could have taken all the camels. They could have killed us! We could all be dead! But—we are still here!”

He is right! We are alive—and it feels very good.

The next few hours are some of the happiest of the whole journey. We frolic like kids in the sparkling oasis pools. We wash our bodies over and over again. We eat dates from the trees, drink endless glasses of mint tea, and doze in the shade of the palms, breathing the dry desert air and rejoicing in our freedom to enjoy another day. We were indeed alive!

The journey to the coast takes four days. It is an unfamiliar route for Ali, but as we cross the dry riverbed of the Oued al Khatt we can see the coastal plain ahead of us and the sun glinting on white villages and the distant Atlantic Ocean.

At a small oasis we all dismount and sit together in the sand for a final time. We are tired and silent. We all know we have experienced the end of an era. Border wars and guerrilla piracy are anathema to the old-fashioned ways of desert trading. Ali says very softly what we are all thinking: “There can be no more. This is our last caravan.”

We are slipping into melancholy again. Even the chirpy Saiid is looking glum. Then Abdulali, who has hardly said a word since our imprisonment, begins giggling like a little girl. We all turn and watch. In his lap is a bunch of delicate light-colored dates he’d knocked from one of the palm trees by the spring and he’s eating them with unchecked abandon.

“Deglet nour!” (his beloved “fingers of light” dates), he says and smiles at each one of us in turn. “Allah always provides.”

He pops two more dates into his mouth to emphasize his point.

“Always!”

And somehow, in spite of everything that’s happened, we just can’t stop laughing.

SCOTLAND—THE OUTER HEBRIDES

The storm was sharp and violent. Winds shrieked like banshees across the brown-gray wilderness of dead heather and bare boulders. The normally still, almost sinister, surfaces of the black lochans among the bogs were whipped into froth by the gale; the brittle marsh grass lay broken below the eroded edges of ancient peat banks.

A primeval scene—no signs of habitation anywhere, no welcoming curls of smoke, no walls, no trees, no dainty patches of moorland flora here among the eroded stumps of Archean gneiss, breaking through the peat like old bones on an almost fleshless torso. On the wild moors of the Outer Hebrides island of Harris, forty miles out in the Atlantic off the northwestern highlands of Scotland, I sheltered in a hollow among Europe’s oldest rocks, formed more than three billion years ago, gouged and rounded in three ice ages and sturdy enough to withstand three more.

There’s a Hebridean Gaelic saying: “When God made time, he made plenty of it,” and here, on the desolate slopes of Bleaval mountain, you sense the infinitely slow passage of time. This is a fine place to know the insignificance of man and wonder if this is how the earth may have looked at the very beginning.

And then—an abrupt transformation! The storm passes on, whirling out over the Sound of Shiant, heading for the dagger-tipped peaks of the black Cuillins on the Isle of Skye, crouched on the eastern horizon. The sky is suddenly a sparkling blue, the sun warm, and far below is a scene that would seduce the most ardent admirer of Caribbean islands: great arcs of creamy shell-sand beaches, fringed by high dunes, and a turquoise-green ocean gently deepening to dark blue, lazily lapping on a shoreline unmarked by footprints for mile after mile….

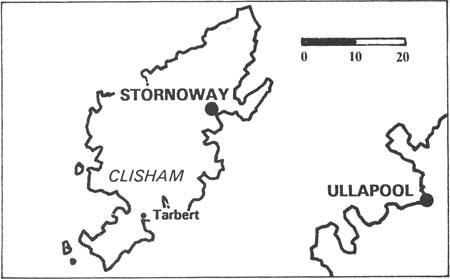

“Aye—it’s a magic place you’re going to,” said Hector Macleod at the Ceilidh Place pub in Ullapool, a small port town of tiny whitewashed cottages overlooking Loch Broom on Scotland’s west coast. “Some of the kindest people you’ll ever meet—not pushy mind…” Hector paused and then winked. “Well—they’ve a bit of the magic too.” The barman laughed. “They’re Gaelic and Celtic—what can y’expect?—they’ve all got the touch of Irish in ’em!”

For years I’ve been promising myself a journey to these mysterious islands where the Scottish crofting families still weave the famous Harris tweed in their own homes. “There’s over two hundred different islands out there,” Hector continued, “and there was a time—not so very long ago—when every one had its crofters and its own kirks. But then came the terrible famines—the potato famines—and all these great ‘clearances’ in the middle of the last century when the big lairds got together, kicked many of the people off the land—sent them to Canada and suchlike places—and moved the sheep in. Now I think there’s only thirteen islands with any people at all. Maybe less. Crofting’s a hard life.”

A frisky three-hour ferry journey from Ullapool brought me, a little shaken, to Stornoway, capital of the 130-mile-long Outer Hebrides chain. This small town of 6,000 people is the hub of life on the main island of Lewis and Harris, and the epitome of all the best and worst of island life. Fine churches, big Victorian houses, lively industries, new hotels, even a mock castle and a colorful fishing fleet mingle with bars, pool halls, fish and chip shops, and, according to one local church newspaper, “palaces of illicit pleasures whose value to the community is highly questionable,” referring to the town’s two rather modest discos.

Stornoway’s stern Calvinistic appearance was no great inducement to dallying so I was soon off across the bleak moors and peat bogs looking for the tweed makers in the heart of Harris. And that’s how I got stuck in the storm.

But as the weather cleared, I came down slowly from the wind-blasted tops and could see, far below, the thin crofting strips on the fertile

machair

land fringing the coastal cliffs and dunes.

They say the milk of cows grazed on the machair in the spring and summer is scented by the abundance of its wild-flowers—primroses, sea spurrey, campion, milkwort, sea-pink, sorrel, and centaury. Each strip, usually no more than six acres in all, had its own steep-gabled crofter’s cottage set close to the narrow road, which wound around boulders and burns. Behind each of the cottages lurked the sturdy remnants of older homes, the notorious “black houses” or

tigh dubh

. Some were mere walls of crudely shaped bedrock, six feet thick in places; others were still intact, as if the family had only recently moved out. They were roofed in thick thatch made from barley stalks, held in place by a grid of ropes, weighted down with large rocks. Windows were tiny, set deep in the walls, and door openings were supported by lintel stones often over a foot thick. Nearby were dark brown piles of peats, the

cruachs

, enough to heat a house for a whole year.

Looking at these black houses, which until recently formed the communal living space for families and their livestock, you feel pulled back in time to the prehistoric origins of island life, long before the invasions of the Icelandic tribes and the Norsemen from Scandinavia, long before the emergence of the Celtic clans of the MacLeods, the MacAulays and the MacRaes.

All around the islands are remnants of ancient cultures in the form of

brochs

(lookout towers), Bronze Age burial mounds, stone circles, and the famous standing stones of Callanish on Lewis, thought to have been a key ceremonial center for island tribes since 2000

B.C.

The ponderous tigh dubh houses seem very much of this heritage, and I experienced a strange sense of “coming home” again to something half remembered, deep, deep down, far below the fripperies and façades of everyday modern life. Something that sent shivers to my toes.

Lord Seaforth, one of the islands’ numerous wealthy “utopian benefactors” during the last century, was anxious to improve “the miserable conditions under which these poor scraps of humanity live” and ordered that “at the very least a chimney should be present and a partition erected between man and beast in these dark hovels.” But apparently the crofters were quite content to share their living space with their own livestock. They also considered the quality of peat soot vastly superior as fertilizer for their tiny “lazybed” potato plots. The smoke was allowed to find its own way through the thatch from the open hearthstone fire in the center of the earthen floor.

And in spite of such conditions, the crofters were known for their longevity and prolific families. Dr. Samuel Johnson, accompanied on an island tour by the ever-faithful Boswell in 1773, put it down to island breakfasts! “If an epicure could remove himself by a wish,” Dr. Johnson remarked, “he would surely breakfast in Scotland.” I concur wholeheartedly. My first real Scottish breakfast came at the Scarista House hotel overlooking the Sound of Taransay on Harris and included such traditional delights as fresh oatmeal porridge, smoked herring kippers, peat-smoked bacon, black pudding, white pudding, just-picked mushrooms and tomatoes, free-range eggs, oatcakes, bannock cakes, scones, honey, crowdie cream, home-churned butter—everything in fact except the once customary tumbler of island whiskey, “to kindle the fire for the day.”

“Och, the breakfasts are still very fine,” agreed Mary MacDonald, postmistress of Scarista village. I had made the long descent from Bleaval and sat by her blazing peat fire drinking tea and nibbling her homemade buttery shortbread. “The world’s getting smaller everywhere,” she told me. “Things are changing here too—we talk in Gaelic about

an saoghal a dh’fhalbh—

‘the world we have lost’—but you can always find a good breakfast!”

I wondered about the changes.

“Well we’re losing a lot of the young ones, that’s always a big problem. But those that stay still work at the crofting and keep up the Gaelic.” She paused. “I miss the old ceilidhing most I think. We used to gather at the ceilidh house to talk about local things and listen to the old tales by the

seannaicheadh

—an elder village storyteller. Now they’re a bit more organized, more of a show at the pubs with poems and songs and such. Not quite the same.”

I asked about the famous Harris tweed makers of the islands. “Och, you’ll find plenty of them—more than six hundred still I think—making it the old way in their own homes on the Hattersley looms. You can usually hear the shuttles clacking way back up the road.”

Mary was right. I went looking for Marion Campbell, one of Harris’s most renowned weavers, who lived in the tiny village of Plocrapool on the wild eastern side of the island, where the moors end dramatically in torn cliffs and little ragged coves. And I heard the urgent clatter of the loom echoing against the bare rocks long before I found her house, nestled in a hollow overlooking an islet-dotted bay.

Through a dusty window of the weaving shed I saw an elderly woman with white hair working at an enormous wooden contraption.

“Aye, come in now and mind the bucket.”

The bucket was on the earth floor crammed in between a full-size fishing dinghy, lobster pots, a black iron cauldron, cans of paint, and a pile of old clothes over the prow of the boat, just by a crackling peat fire, which gave off a wonderful “peat-reek” aroma.

“You can always tell a real Harris tweed,” Marion told me. “There’s always a bit of the peat-reek about it.”

She worked her loom at an alarming pace and the shed shook as she whipped the shuttle backward and forward between the warp yarns with bobbins of blue weft. I watched the blue tweed cloth, precisely thirty-one inches wide with “good straight edges and a tight weave” grow visibly in length as her feet danced across the pedals of the loom and her left hand “beat up” the weft yarns, compacting them with her thick wooden “weavers beam.” Then her sharp eyes, always watching, spotted a broken warp yarn. “Och! I’ve been doing this for fifty-nine years and I still get broken ones!” She laughed and bounced off her bench, which was nothing more than a plank of wood wrapped in a bit of tartan cloth. “And mind that bucket.”

I looked down and saw it brimming with bits of vegetation, the color of dead skin and about as attractive. “That’s crotal. Lichen—from the rocks. For my dyes.” In the days before chemical dyes most spinners and weavers made their own from moorland plants and flowers—heather, bracken, irises, ragwort, marigolds—whatever was available.

“I’m the last one doing it now,” Marion told me. “By law all Harris tweed has to be handwoven in the weaver’s own home on the islands here from Scottish virgin wool, but I’m the last person doing it the really old way—dyeing my own fleeces, carding, making my own yarn, weaving—I even do my own ‘waulking’ to clean the tweed and shrink it a bit. That takes a lot of stamping about in Wellington boots!”

I pointed to a pile of tan-colored fleece and asked if it had been dyed with the lichen. Marion giggled. “Ooh—no, no that’s the peat—the peat soot. Makes a lovely shade.” I suppose I looked sceptical. “Wet your finger,” she told me, so I did and she plunged it into a pot of soot by the boat. “Now rub it off.” I obeyed again and—surprise—a yellow finger! Her laughing made the shed shake. “Aye, you’ll be stuck with that now for a while.” Three days actually.

Later I sat by her house overlooking the Sound of Shiant as Marion spun new yarn for her bobbins. On an average day she weaves a good ten yards of tweed. “I do all the main patterns—herringbone, bird’s-eye, houndstooth, two-by-two. I like the herringbone. It always looks very smart.” On the hillside above the house I could see a crofter walking among his new lambs in the heather; out on the sound another crofter was lifting his lobster pots.

“You’re a bit of everything as a crofter,” Marion told me as her spinning wheel hummed. “You’re a shepherd, a fisherman, a gardener, you collect your seaweed for fertilizer, you weave, build your walls, cut and dry your peats, shear your sheep at the fank, cut hay, dig ditches—a bit of everything. In the past you’d leave the croft and go to your

shieling

in the summer to graze the cows, and each night the girls would carry the milk back to make butter. I remember that so well.”

And I remember my walks on Harris, particularly around the peaks of Clisham and West Loch Tarbert.

I picked a clear day for one of my rambles here and lay back on a soft hillside basking in a warm sun. A curlew flung out its dismal warning somewhere behind me and meadow pipits and greenshanks chirped. Among the rocks, dappled with lichen and puffy with tufts of heather, were scatterings of starry saxifrages, butterwort, and roseroot. Breezes off the ocean shook their leaves and bowed the brittle nardus grass. I thought of nothing really important. At one point I may even have been thinking of nothing at all, which is a rather difficult thing to do for any measurable length of time, for me at least.

Some obscure guru with a name longer than his beard once offered the thought to an impatient world that “in nothing is everything.” The world as usual ignored him, and the guru eventually disappeared into his own nothingness, claiming as he departed that he was now everything. I didn’t quite understand at the time and I’m not sure I do now. It sounded like one of those Zen wordplays, infinitely complex and infinitely obvious, and a little too obscure for most Western minds to grasp.

And yet there are moments—tiny capsules of nontime—when the incessant chatterings of the mind cease. One is touched and exposed, and a link is made with something beyond the body. Most people are fortunate if they experience this kind of sensation a dozen times in a life. But each occasion can never be forgotten. Names have been given to the experience—spiritual awakening, a sense of the infinite, universal harmony. I had that sensation, a little shiver of awareness, on that hillside, and it more than made up for the ankle-busting climbs up Clisham.

And I too remember my other moments on these islands—some sad, all revealing. I remember the shepherd, Allistair Gillis, recently returned after years of adventure in the merchant navy, only to lose a third of his ewes in a long cold winter and spring. “You can’t win in a place like this,” he told me with Gaelic melancholy. “All you can do is pass your time here. Just pass your time as best you can.”