Back of Beyond (3 page)

And we just floated with it as best we could. We found a deeply imbedded love for travel and the open road; we also found a need to give back something to the world (we both work with the blind in developing countries); and we found a need to be alive to life every day through creative endeavors (many of which make no economic sense whatsoever!).

Which brings me finally to this book, a culmination of fifteen years of travel and travel book writing. I’ve explored a good part of our earth in search of people and places that possess an essential integrity, truth, and centeredness—wild places, secret places, unspoiled nooks and crannies on the backroads, and people who seem to live life as fully as they are able—finding, as Joseph Campbell would say, their own “bliss.”

I love travel with a passion, the good days and the bad. And I don’t care to analyze the reasons too deeply—running to, running from, inner journeys, outer journeys, fear of commitments, fear of dying, fear of missing out on things—all of the above, or none. Who cares?

My travels are open-eyed experiences of the unknown, the child in the man still romping on from adventure to adventure; trying to learn, to understand, and to share the joys of “earth-gypsying.”

May you enjoy all your journeys, too.

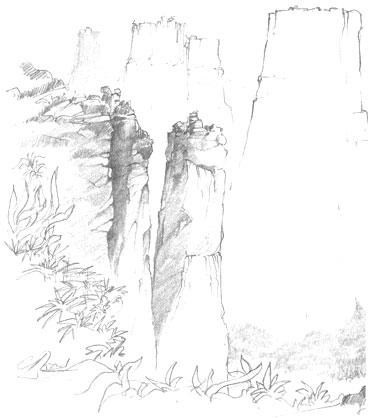

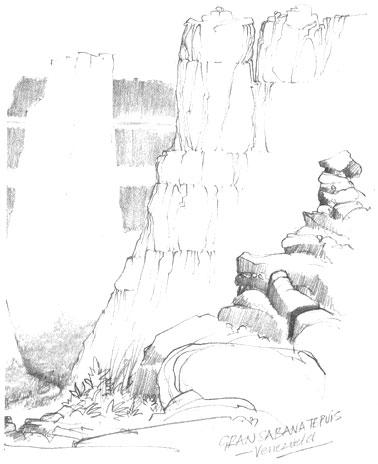

VENEZUELA’S GRAN SABANA

We’d made it!

The clouds, swirling like wraiths throughout our long climb up the five-thousand-foot-high vertical mountain, suddenly lifted. My two Indian guides hauled me the last few feet through the mud and mossy slime onto a slab of cold black rock. We were utterly exhausted. I had never felt so drained. The ascent had taken two long days, up from the gloom and tangle of the jungle, along slippery ledges hardly wide enough for a toehold, shinnying up wet clefts, and always cursing the constant mists that cut visibility to a few murky feet.

Many times I thought we’d reached the summit only to peer through fleeting holes in the cloud and see the rock face rising up, endlessly.

I was convinced we’d never arrive but decided to keep going as long as my guides seemed optimistic. It was hard to tell what they thought. I had only the mountain to worry about. They, on the other hand, brought with them an ancient tribal inheritance plagued with terrible legends and fears of

curupuri

, the constant lurking spirit of the forest, and a dozen other demonic entities that kept most of their peers well away from these strange, pillarlike mountains—the mysterious

tepuis

of Venezuela’s Gran Sabana.

But this truly was the summit. As the clouds melted, I could see a barren plateau of incised rocks stretching away into the sun. A cold wind tore across the wilderness, screaming and howling in the clefts. There were no trees. Spongy clumps of dripping moss clung to the more sheltered sides of broken strata. The rest of the summit was as arid as a stone desert of scattered black stumps, frost-shattered and worn into shapes like petrified figures.

I was shivering, dazed with fatigue, amazed by the bleakness of the landscape—and elated. After years of dreams and half-baked schemes, I was finally here. One of few, if any, white men ever to stand on this towering tepui in one of the remotest regions on earth, a true lost world, where you could see forever across an infinity of Amazonian jungle.

I blame it all on Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.

Way back in 1912 the world-reknowned creator of Sherlock Holmes released his new novel

The Lost World

to enthusiastic reviews. It was based on a tantalizing premise. Somewhere on the most remote northern edge of the Amazon Basin, an eccentric professor from England had discovered a primeval lost world of flat-topped sheer-sided mountains, thousands of feet high, soaring out of impenetrable jungle. He had seen evidence of prehistoric creatures, been attacked by pterodactyls and returned, after numerous misadventures, to proclaim the existence of land where time had stood still, a bastion of ancient life forms long considered extinct.

Expecting adulation and fame from his discoveries he found himself instead ostracized by skeptical scientists and relegated to the ranks of crankishness. Sir Arthur begins his tale as the professor sets out with a group of fellow explorers to rediscover this lost world and return with tangible evidence that the earth is still a place of great mysteries and secrets. The journalist of his fictional story records the outset of the journey in prose designed to excite the imagination of his readers (and this reader in particular): “So tomorrow we disappear into the unknown. This may be our last word to those who are interested in our fate. I have no doubt that we are really on the eve of some of the most remarkable experiences.”

I first read the book as a child and vowed to my ever-patient parents that one day I’d find this place and lead my own expedition to the top of one of those impossible mountains.

Years passed but the idea never faded. I learned that Sir Arthur had indeed traveled in the remotest parts of southern Venezuela and that these strange mountains, hundreds of eight-thousand-foot-high tepuis, did in fact exist on the fringes of the Amazonian basin.

So finally, I went to Venezuela to see them for myself.

Set high above the steamy coastal plain, Caracas overflows the edges of its mountain bowl, bathed in balmy springlike breezes. The temperature rarely exceeds eighty degrees here. The capital of Venezuela is a vigorous place, teeming with traffic on spaghetti strands of freeways, booming (until recently at least) with new oil-cash affluence. Scores of high white towers—real fat-cat architecture—rise above boulevards and formal parks.

On the green foothills, pantile-roofed minipalaces peep out at the city from behind pruned bushes and elaborate gardens. Lower down, hundreds of tiny houses—the ranchitos—cling together with Greek hilltown audacity on craggy cliffs. Venezuelans tend to dismiss these barrios with their tin roofs and lopsided walls as “places for the immigrants” (newcomers drawn to this progressive Latin American nation by its wealth and political stability). They point instead to the abundant riches of the city—proud European-style churches, an immaculate metro, theaters, world-class hotels, enough fine restaurants to keep a discerning epicure busy for a decade, and the material abundance of the Sabana Grande, a two-mile-long traffic-free shopping extravaganza with outdoor cafés and fountains and always filled with immaculately dressed citizens (the fashion consciousness here far exceeds that of New York’s Fifth Avenue).

But I hadn’t come for city life, no matter how seductive and cosmopolitan. My only concern were the tepui mountains of the far southeast. I was impatient to reach my lost world.

At least in that respect I had much in common with the early explorers of this vast country seeking their fountains of youth and their El Dorado fantasies. Venezuela is wrapped in fantasy. Even its name, which translates as “Little Venice,” and is attributed to Alonso de Ojeda, who sailed along the coast in 1499, a year after the discovery of the country’s Orinoco River by Columbus, evokes the romance of Indian coastal villages once built on stilts out in the shallow bays of the jungle-covered coast. It was only much later that settlers discovered the reality, and scale, of this wild and broken land with its towering ranges of snow-peaked mountains, deserts, vast plains teeming with wildlife, huge marshy deltas, immeasurable rain forests, fertile valleys—and the unique region of the tepuis.

But in those early days of true exploration, the dream was all. And what dreams! Filling the endless jungles not only in Venezuela but all the way down through Brazil and into Argentina. And the dreamers. What splendid lotus-eating adventurers they were, driven on for years and thousands of miles of deprivation, wasting whole armies in the process, carrying their dreams like glorious banners in their minds, tapping the depths of kingly coffers, and always singing the same refrain, “the next valley, the next mountain, the next time men…”

It all really began in the glorious Elizabethan age with a perfect combination of the avaricious Queen Elizabeth I and her power-infatuated courtiers and privateers, particularly Sir Walter Raleigh. Restless Raleigh first arrived at the mouth of the Orinoco in 1595, determined to find the golden city of El Dorado and the mythical “Mountains of Crystal” (he hoped for diamonds) in the southeast. He planned to return to England in his galleons, bulging with precious metals and stones, to receive his rewards of power, wealth, and fame from the hand of his beloved Queen. His journal captures his enthusiasm: “Spaniards claim to have seen Manoa, the one they call El Dorado, a place whose magnificence, treasure and excellent location outshine any other in the world.”

But alas for poor Sir Walter, royal patronage and patience ran out eventually as El Dorado proved more elusive than expected, and as a result of his excesses in South America, politicking and plundering, he found himself imprisoned “at the pleasure of the Queen” in the Tower of London and ultimately headless for his troubles.

His contemporary, the famous Spaniard de Berrio, sought endlessly for his own city of gold in the green hills of Amazonia, and dozens of other expeditions seeking everything from tribes of female warriors to lost youth-giving fountains, eventually floundered and fizzled out.

Much more recently the notorious explorer Col. Percy Fawcett gained worldwide fame for his Seven Cities expedition deep into the southern jungles. He was convinced he was on the trail of Plato’s Lost City of Atlantis (although if you read Plato’s admittedly vague geographical hints you may wonder why he chose such a dismal place when it is quite obvious—to me at least—that the Greek philosopher was referring to the Azores, way out in the mid-Atlantic between Portugal and the United States).

But there are still those who believe that Col. Fawcett found his destination. Newspapers carried wild speculations for years following his disappearance in 1925, fantasizing about his transformation into a king over untold Indian multitudes, basking in unbelievable riches, fathering whole tribes of light-skinned descendants….

More recent reports however have suggested his rather messy and inauspicious demise at the hands of irate Indian skull bashers who resented the man’s casual intrusion into their territory, certainly a more realistic assumption and not at all the stuff of which legends are made.

My only hope was that skull bashing was a thing of the past. I had no desire to make this elusive lost world of the Venezuelan tepuis a lost world for me.

You could hear the excitement, even in the pilot’s voice over the intercom: “The cloud cover is lifting. We should be able to see the mountains today. I shall be flying as close as possible to the Angel Falls. Please fasten your seat belts. It will be bumpy.”

That was nothing new. The whole journey had been bumpy. Five hundred miles from Caracas in a small fifty-seat plane bouncing across the thermals thrown up by the dry red plains and brittle ridges below us. Then up through the clouds, into the blue, peering out of tiny windows, seeking signs of the tepuis.

But he was right about the clouds. We descended through thinning haze, and down below was the jungle. Mile after mile after mile of green sponge in every direction, with occasional flashes of serpentine rivers and streams meandering through this eternity of green.

Then the first tepui. A huge vertical shaft of dark strata cut by creamy clefts rising abruptly out of the jungle. Its profile seemed familiar at first. We edged closer to the towering rock face. A close encounter. Precisely that—

Close Encounters

. The Devil’s Tower in Wyoming, that mystical volcanic monolith replicated by Richard Dreyfus in charcoal sketches, then mashed potatoes, then enough wet clay to fill his living room. But not one. A dozen of them here and much larger than the Devil’s Tower, separated by scores of square miles of jungle, their flat barren tops, fractured and split, scraping the clouds; the last magnificent stumps of a vast plateau of sandstone and igneous rock, almost two billion years old.

Once a part of the great land mass of Gondwana, the plateau was a notable feature of the earth even before South America and Africa were separated by massive tectonic plate movements over two hundred million years ago. Subsequent cracking of the high plateau led to its gradual disintegration by erosion into individual flat-topped tepuis. Rather like the buttes of Arizona’s Monument Valley transplanted into an Amazonian setting.

“Angel Falls approaching on the right.”

And there it was. Tumbling in lacy sprays off the summit of Auyantepuy, an uninterrupted drop of 3,212 feet, the tallest waterfall in the world, billowing in a crochet cascade, sheened by the afternoon sun.

There were more falls. Smaller but no less impressive, spuming off the black cracked top of the tepui and disappearing in a hundred streams far below in the unbroken jungle. And beyond, the hazy silhouettes of other tepuis, stretching out across the green infinity into the 1,500-mile-wide Amazonian basin itself.

Finally, after years of dreaming, I had arrived at the edge of Sir Arthur’s lost world.

Base camp at Canaima was more than adequate. A cluster of chalets in a jungle clearing catering to the more adventurous tourists, anxious to catch a glimpse of tepui country and the roaring falls on the Carrao River. For most visitors this was the beginning and end of their journey, a lovely interlude of meals and cocktails on a shady terrace overlooking the falls, maybe a river excursion to the base of Angel Falls for the explorer types, and then back to the hectic hedonism of Caracas and the coastal resorts.