Bang!

Copyright © 2005 by Sharon G. Flake

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or

mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information or storage retrieval system,

without written permission from the publisher. For information address Hyperion Books for Children,

114 Fifth Avenue, New York, New York 10011-5690.

Printed in the United States of America

First Edition

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Flake, Sharon.

Bang! / by Sharon G. Flake.— 1st ed.

Summary: A teenage boy must face the harsh realities of inner city life, a disintegrating family,

and destructive temptations as he struggles to find his identity as a young man.

ISBN 0-7868-1844-1

[1. Identity—Fiction. 2. Coming of age-Fiction. 3. Family problems—Fiction. 4. African-Americans—Fiction.] I. Title.

PZ7.F59816Ban 2005

[Fic]—dc22

2005047434

- Boys Ain't Men . . . Yet

- Chapter 1

- Chapter 2

- Chapter 3

- Chapter 4

- Chapter 5

- Chapter 6

- Chapter 7

- Chapter 8

- Chapter 9

- Chapter 10

- Chapter 11

- Chapter 12

- Chapter 13

- Chapter 14

- Chapter 15

- Chapter 16

- Chapter 17

- Chapter 18

- Chapter 19

- Chapter 20

- Chapter 21

- Chapter 22

- Chapter 23

- Chapter 24

- Chapter 25

- Chapter 26

- Chapter 27

- Chapter 28

- Chapter 29

- Chapter 30

- Chapter 31

- Chapter 32

- Chapter 33

- Chapter 34

- Chapter 35

- Chapter 36

- Chapter 37

- Chapter 38

- Chapter 39

- Chapter 40

- Chapter 41

- Chapter 42

- Chapter 43

- Chapter 44

- Chapter 45

- Chapter 46

- Chapter 47

- Chapter 48

- Chapter 49

- Chapter 50

- Chapter 51

- Chapter 52

- Chapter 53

- Chapter 54

- Chapter 55

- Chapter 56

- Chapter 57

- Chapter 58

- Chapter 59

For Alvera Johnson,

Gwen Evans,

and several of the men in their lives:

Patrick Evans,

Charles Linton,

James Linton,

Corden Porter,

Brandon Radford,

and

Jesse Johnson

To Cassandra Allen

and the man in her life, Ryan

For Suzanne Davis and her men, Chuckie and Little Chuck

And to Francine Taggert and her two fine men,

Charles and Charles Ross

It has been a pleasure having you in my life and witnessing the fruit of your love.

Boys ain’t men . . . yet. They are sneakers with strings untied Broken bikes and blackened eyes Fast footraces and dirty faces But they ain’t men, not yet.

Boys ain’t men . . . yet. They are stolen kisses from a young girl’s cheek Sagging pants strutting up the street Homework turned in two days late Video wizards and basketball greats But they ain’t men, not yet.

Boys ain’t men . . . yet. They are skirt chasers and moneymakers Late-night rides, muscles and pride Prom dates handing out flowers and grins Ready to take on the world and win But they ain’t men, not yet.

Boys ain’t men . . . yet. They are tall, giant reeds, trying to survive Strong arms pushing trouble aside Corner sitters, watchers and seekers On the lookout for men willing to lead ’em.

—Sharon G. Flake

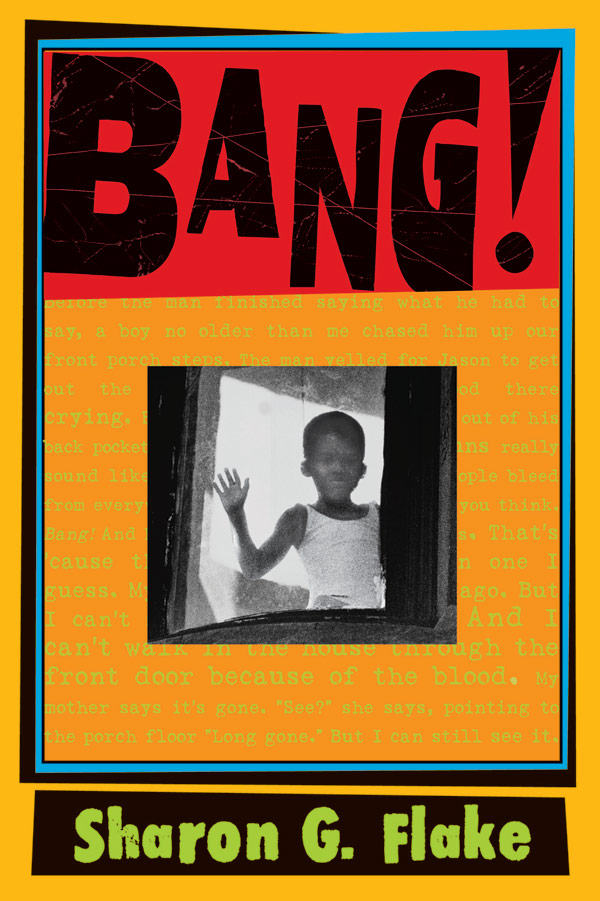

THEY KILL PEOPLE where I live. They shoot ’em dead for no real reason. You don’t duck, you die. That’s what happened to my brother Jason. He was seven. Playing on our front porch. Laughing. Then some man ran by yelling, “He gonna kill me. He’s gonna—”

Before the man finished saying what he had to say, a boy no older than me chased him up our front porch steps. The man yelled for Jason to get out the way. But Jason just stood there crying. Right then, the boy pulls out a gun and starts shooting.

Bang!

Guns really sound like that, you know.

Bang!

And people bleed from everywhere and blood is redder than you think.

Bang!

And little kids look funny in caskets. That’s ’cause they ain’t meant to be in one, I guess.

My brother died two years ago. But I can’t stop thinking about him. And I can’t walk in the house through the front door no more because of the blood. My mother says it’s gone. “See?” she says, pointing to the porch floor and the gray wooden chairs. “Long gone.” But I can still see it. I can. So I come into the house through the back way. Stepping over the missing stoop Jason used to put his green plastic soldiers in. Opening the iron gate that my dad put up to keep trouble out. Going inside the house and not looking at my brother’s room, because if I even see his door, I cry. And a thirteen-year-old boy ain’t supposed to cry, is he?

The day Jason died I was with Journey—a horse. She stays at Dream-a-Lot Stables, not far from where I live. It’s a broke-down stable where kids hit her with rocks and try to make her eat sticks. But my father, he taught me and Jason to ride Journey, and brush her good. So even though she ain’t ours, Journey likes us best. The man who owns the stables and rents out broke-down horses for five bucks an hour would let us ride for almost free, long as we cleaned Journey’s stable first. So that morning, after my mom and dad went to work, I left Jason home by hisself. I walked to the stables and brushed the flies and dirt off Journey’s blond coat. I swept up turds as big as turtles, and rode Journey all the way home—up the avenue and past Seventh Street, between honking cars, slow buses, and grown-ups who patted her butt, then got mad when she broke wind in their faces.

When I got home, Jason was on the porch. He asked me to play toy soldiers with him. I wouldn’t. Journey was thirsty. So I went around back to get a hose so she could drink. That’s when I heard the man yelling, and Jason screaming my name. I ran to the front of the house. The boy chased the man up our steps and onto our porch. Journey shook her head and stomped her feet on the pavement. The gun went off. The hose in my hand soaked the porch, squirted the dead man and splashed blood everywhere. Neighbors tried to pull it away from me, but I wouldn’t turn it loose. That’s what they say anyhow.

After Jason was gone, I saw a psychologist for six months. But my father didn’t like that, so I quit going. “You a man, not no sissy baby girl,” he said when he found me one day behind the couch, crying.

My mother got mad at him. “I’m gonna cry over my baby boy till I die,” she said, hugging me. “Guess Mann here’s gonna cry awhile too.”

My father used to be in the army, so he don’t cry much. And he don’t want no boy crying all the time neither. That’s what he tells me anyhow.

A week ago my mother told my father I needed help. “We all do,” she said, sitting down on the living-room floor next to me. “It’s been nearly two years since Jason died, and it hurts like it happened this morning.”

My father stood behind his favorite brown leather chair. “I don’t need no help. And him,” he said, pointing to me, “ain’t nothing that momma’s boy needs but a good old-fashioned butt-kicking.”

I am not a momma’s boy, but since Jason died, that’s what my dad calls me. “People die,” he said. “Little people die too. Get over it.”

My mother jumped up. Her knee knocked me in the chin. I held my mouth, because I bit my tongue and I didn’t want her feeling bad about that. “So you’re over it, huh?” she said, running up to the window and pulling back the white curtains. “Yeah, right,” she said, holding on to the heavy, iron bars that cover every window and door in our house.

My mother walked past my father and unlocked the drawer to his desk. She picked up his .38 and stuck her arm high in the air like she does when she’s hailing a cab. Then she reached in the drawer with her other hand and pulled out a rusty hunting knife big enough to cut your arm off. “He cries,” she said, looking at me and pointing the gun at my father, “but you, you—”

“Shut up, Grace. I’m warning you.”

My mother kept talking. Next thing I knew my father was pulling his gun and knife out her hands and locking them back in the drawer. She hugged him from behind. “He didn’t deserve to die. He was sweet and smart and gave hugs when you—”

My dad covered his ears with his hands.

“Grace!”

She ran to the window and yelled out. “You killed us too! We look like we still alive but we dead. Rotten inside.” She punched her flat stomach. Bit down on her arm. “Ja. . . Ja. . . ”

My father shook her. “Don’t say his name! Don’t ever—”

My mother’s eyes are big red circles with black bags under ’em that won’t go away since Jason died. “He’s gonna be nine in a few months,” she said. “We have to make a cake. Buy him something special.”

My dad spit at the trash can. Some made it in. The rest stuck to the outside like a slug. “A dead boy don’t need no presents. I told you that last year.”

We always get cakes on our birthdays. And we always sing songs and make the day extra special, not just for me and Jason, but for my mom and dad too. My mother says it wouldn’t be right to leave Jason out now. So she gets him presents he can’t open and makes him cakes he can’t eat.

My dad said what my mother never wants to hear. “Grace. He’s gone. And he ain’t never coming back.”

I watched her, ’cause I knew them words were gonna get her too sad to make supper, or laugh when the funny shows came on TV tonight.

My mother went to the front door and opened it wide. Then she ran onto the porch and yelled for Jason. My dad ran after her. But by the time he got there, she was on her knees picking up little green soldiers we find on the porch sometimes but can’t figure out just how they get there. She stomped her feet. “Jason. You come home. Come home right now!”

My father kneeled down beside her. He rubbed her lips, then covered up the rest of her words with his fingers. And then he cried, right along with her.

THREE DAYS LATER my father apologized. He said he was sorry for making my mother so upset. Sorry for saying all them things about Jason. She was glad he said it. After that, they got dressed and went to the movies. I went to my room and tried to figure out why she couldn’t figure out that tomorrow he was gonna say them same things all over again.

“He can’t help it,” she says all the time. “He just doesn’t know what to do with all the things he’s feeling inside.”

I know she’s right. Only I get tired of him being mean. He used to be different. He used to take us to the park. Slide down snow hills with us and lie in bed between me and Jason and make up stories about two boys walking from here to China. Then Jason died and so did my dad, kinda.

One time, when my mother and him were arguing about the way he treated me, she made me go get some of Jason’s things. I walked over to the middle bookshelf and picked up Jason’s lunch box—the one he had in his hand that day he got killed.

“Give it here,” my mother said. She opened it. Took out the note. “‘Daddy loves you.’”

My father snatched the napkin out her hand and tore it up.

My mother pointed to a Buster Brown shoe box sitting way on top of the bookshelf. “I still got the rest,” she said, talking about the other notes my dad had put in Jason’s lunch box.

Have a nice day,

they’d say.

Meet me after school for coffee,

he’d write. Only he never gave Jason real coffee—just grape juice in a coffee mug. “Us men have to have something strong now and then,” he’d say. That always made Jason laugh.

I got notes every day too, when I was Jason’s age. But when I turned nine, they stopped. My father took me to the yard right after my birthday party that year, and burned them. “What’s between a father and his son,” he said, putting one hand on his heart and the other on mine, “can’t be burned by fire, washed away by water, or destroyed with human hands.” He squeezed me so hard, I couldn’t breathe. Then he gave me a note—the same note he gives me every year on my birthday.

What we have is forever

it says. When I was ten, I got to hold on to the note for ten hours. At thirteen, I kept it for thirteen hours. When my time’s up, I give it back to him until my next birthday. I always liked getting that note. But I don’t believe it no more.