Beautiful Blood

Authors: Lucius Shepard

Tags: #Lucius Shepard, #magical realism, #fantasy, #dragons, #Mexico, #literary fantasy

Beautiful Blood

Copyright © 2014 by Lucius Shepard.

All rights reserved.

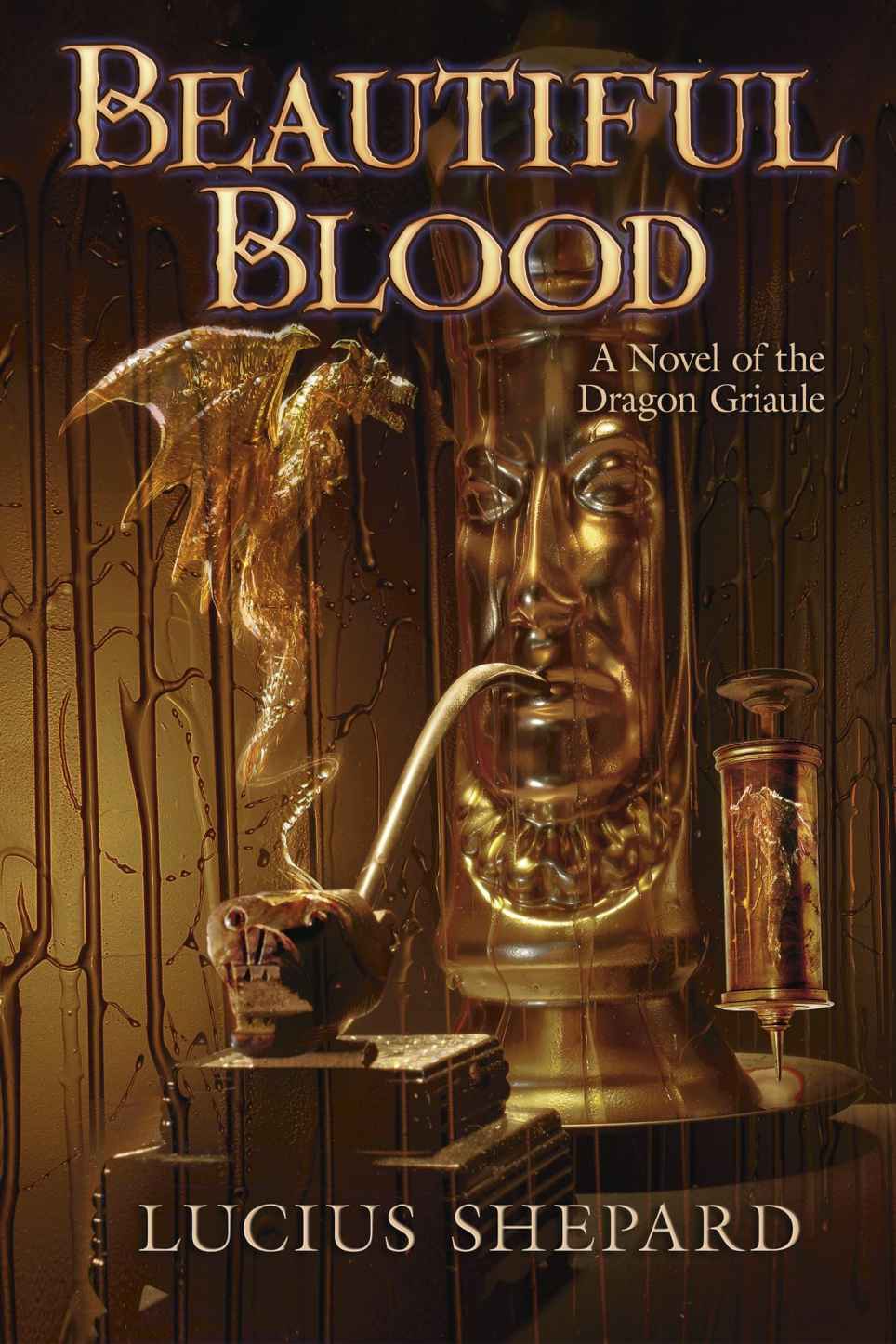

Dust jacket illustration Copyright © 2014

by J. K. Potter. All rights reserved.

Print version interior design Copyright © 2014

by Desert Isle Design, LLC. All rights reserved.

First Edition

ISBN

978-1-59606-653-3

Subterranean Press

PO Box 190106

Burton, MI 48519

By night, the crooked streets of Morningshade resounded with laughter, shrieks and contending musics, and were thronged with drunks, brawlers, vendors, whores, cutpurses, pickpockets and the precious few who were their targets—they pushed, jostled and shouldered their way along beneath a pall of smoke, a sluggish river of humanity dressed in rags and cheap gaud sloshing against the banks of taverns and gin shops, disreputable inns and bawdy houses, ramshackle buildings that leaned together like doddering grey-faced uncles with caved-in top hats made of tarpaper. And over it all, the vast bulge of piceous blackness that was Griaule’s belly and side, from which depended a fringe of vines and clumped epiphytes, some dangling so low they nearly brushed the rooftops, showing in silhouette against the glowing blue darkness of the sky.

“As we pressed closer to the dragon, the crowds thinned, the cooking smells became less pervasive and the buildings grew less densely packed, until at last we came to the wide semi-circle of dirt (the site of a flea market by day) that bordered Griaule’s bent foreleg and great taloned foot. Here there stood a single notable structure, a rickety construction made of weathered boards, replete with gables, bay window and other ornamental conceits—the Hotel Sin Salida, Morningshade’s most infamous brothel. The hotel incorporated two of the talons into its foundation (they flanked the front door, forming a massive entranceway of age-yellowed bone) and rose an improbable nine stories, seeming on the verge of collapse, though it was actually quite stable, anchored by thick hawsers and cables to Griaule’s scaly ankle, against which it was braced. With its spindly frame and treacherous outside staircases, it resembled a shabby, eccentric castle.

“Standing about on the steps were a half-dozen women with their breasts exposed, wearing satin trousers, and a larger number of unsavory-looking men, some carrying machetes. Scampering in and out amongst them, playing a game of tag, were a handful of children dressed in bright blue pants and blouses, a uniform that marked them as property of the hotel. They were initially oblivious to our approach, but as we came within earshot, they turned toward us, children and adults alike, displaying a disturbing unanimity of intense focus and neutral expression, as if responding to an inaudible signal—but then, almost instantly, they relaxed from this rigid posture and ran toward us, smiling and with open arms, inviting us to partake of the pleasures of the house.”

Braulio DaSilva,

The House of Griaule

1

At the age of twenty-six, Richard Rosacher, newly a medical doctor (he advertised the fact to no one, his diploma resting beneath a heap of soiled clothing on his bedroom floor), was possessed of a devout single-mindedness such as might have been attached to an educated man twice his age and of infinitely larger accomplishment. From earliest childhood he had been fascinated by the dragon Griaule, that mile-long beast paralyzed millennia before by a wizard’s spell, beneath and about which the town of Teocinte had accumulated; and, as he approached his majority, that fascination was refined into an obsessive scientific curiosity. Running contrary to this virtue, however, was a wide streak of adolescent arrogance that left him prone to fits of temper. His rooms, occupying a portion of the second story of the Hotel Sin Salida in Morningshade (the poorest quarter of Teocinte, tucked so close beneath the dragon’s side, it never knew the light of dawn), offended him not so much by their squalor, but by the poor relation in which they stood to the tastefully appointed surroundings in which he believed a person of his worth should be lodged. While he bore a genuine affection for many who quartered at the inn, rough sorts all (laborers, thieves, prostitutes, and the like), he believed himself destined for a loftier precinct, imagining that someday soon he would converse with poets, artists, fellow scientists, and cohabit with women whose beauty and grace were emblems of sensitive, carefully tended souls. This snobbish attitude was exacerbated by his outrage over the fact that the populace of Teocinte treated the dragon as an object of superstition, a godlike creature who manipulated their actions through exercise of its ancient will, and not as a biological freak, a gigantic lizard whose sole remarkable quality was as a treasure trove of scientific knowledge. Thus it was that when thwarted in his ambitions by Timothy Myrie, a disheveled shred of a man with no ambition of his own apart from that of drinking himself unconscious each and every night, Rosacher reacted along predictable lines.

The confrontation between the two men occurred late of an evening in Rosacher’s sitting room, a narrow space with a sloping ceiling cut by pitch-coated roof beams, the plaster walls painted by the brush of time to a grayish cream, like egg gone off, and mapped by water stains the color of dried urine. Spider webs trellised the corners, belling in drafts that entered through a half-open bay window and, although the breeze carried a certain freshness (along with an undertone of sewage), it was unable to dispel the odor of innumerable sour lives. Rosacher had pushed sofa and chairs all to one end in order to accommodate an oak ice chest and a crudely carpentered workbench whereon rested scattered papers and a second-hand microscope; a cherrywood box containing vials, slides, and chemicals; a dirty dish bearing chicken bones and a crust of bread, the remnants of his supper; and an oil lamp that shed a feeble yellow light sufficient to point up the squalor of the place. Myrie, his pinched features shadowed by a slouch hat, clad in a greatcoat several sizes too large, stood by the bench, striking a pose that conveyed a casual disaffection, and Rosacher—his lean, handsome face, active eyes and glossy brown hair presenting by contrast an image of vitality—glared at him from an arms-length away. He wore a loose white shirt and moleskin knee-britches, and was holding out some crumpled banknotes to Myrie who, to his amazement, had rejected them.

“I need more,” Myrie said. “I thought my heart would stop, I took such a fright.”

“I can’t afford more,” Rosacher said firmly. “Next time, perhaps.”

“Next time? I’ll not be going back there soon. The things I saw…”

“Fine, then. That’s fine. But we had a bargain.”

“Too right we

had

a bargain. And now we’re going to have a new bargain. I need a hundred more.”

Rosacher’s frustration plumed into anger. “It was a simple thing I asked. Any fool could have managed it!”

“If it’s so simple, why not do it yourself?” Myrie cocked an ear, as if anticipating an answer. “I’ll tell you why! ’Cause you don’t much like the thought of crawling into the mouth of a fucking great dragon and drawing blood from his tongue! Not that I blame you. It’s far from a pleasant experience.” He stuck out his palm. “A hundred more’s still on the cheap.”

“Can’t you get it through your head, man? I don’t have it!”

“Then you’re not having your precious blood, either.” Myrie patted the breast of his coat. “Town’s full of crazy folk these days, all wanting souvenirs. Chances are one of them will pay my price.”

Fuming inwardly, Rosacher said, “All right! I’ll get you the money.”

Myrie smirked. “I thought you didn’t have it.”

“One of the girls downstairs will loan it to me.”

“Got yourself a sweetheart, eh?” Myrie made an approving noise with his tongue. “Go on, then. Ask her!”

Rosacher fought back the urge to shout. “Will you at least put the blood in the ice chest? I don’t wish it to degrade further.”

Myrie cast a dubious look at the chest. “I reckon I’ll keep it on my person until I see the hundred.”

“For God’s sake, man! She may be occupied. It may be some time before I can speak with her. Put the blood in the chest. I’ll be back with the money as soon as I can.”

“Which girl is it?”

“Ludie.”

“The black bitch? Oh, she’ll have it to spare. Very popular, she is.” Myrie’s tone waxed conspiratorial, as if he were imparting secret knowledge. “I’m told she’s exceptional. Got a few extra muscles in her tra-la-la.” He leered at Rosacher, as if anticipating confirmation of this fact.

“Please!” said Rosacher. “The blood.”

Acting put upon, Myrie reached inside his coat and brought forth a veterinary syringe filled with golden fluid. He displayed it to Rosacher with an expression of exaggerated delight, as if showing a child a marvelous toy; then he opened the chest, set the syringe atop a block of ice, closed the lid and sat down upon it. “There now,” he said. “It’ll be safe ’til your return.”

Rosacher stared at him with loathing, wheeled about and made for his bedroom.

“Here! Where you going?” Myrie called.

“To fetch my boots!”

Rosacher proceeded into the bedroom and snatched his boots from beneath the bed. It galled him to beg money of Ludie. As he struggled to pull the left boot on, the disarray of his life, patched stockings, a raveled vest, a shabby cloak, all his ill-used possessions seemed to be commenting on the paucity of his existence. A flood of cold resolve snuffed out his sense of humiliation. That he should allow the likes of Myrie to practice extortion! That he should be delayed an instant in beginning his study of the blood! It was intolerable. He flung down the boots and strode back into the sitting room, each step reinvigorating his anger. Myrie shot him a quizzical glance and appeared on the verge of speaking, but before he could utter a word Rosacher seized him by the collar, yanked him upright and slung him headfirst into the wall. The little man crumpled, giving forth a sodden sound. Once again Rosacher grabbed his collar and this time slammed his face into the floorboards. Spitting curses, he rolled Myrie onto his back, lifted him to his feet and threw him against the door. He barred an arm beneath his chin, pinning him there while he groped for the door knob. Blood from his nose filmed over Myrie’s mouth. A pink bubble swelled between his lips and popped. Rosacher wrenched open the door and shoved him out into the corridor, where he collapsed. He intended to hurl a final curse, but he trembled with rage and his thoughts would not cohere. He stood watching Myrie struggle to his hands and knees, deriving a primitive satisfaction from the sight, yet at the same time dismayed by his loss of control. Merited, he told himself, though it had been. Unable to develop an appropriate insult, he kicked Myrie’s hat after him and closed the door.

2

Hematology had been Rosacher’s speciality in medical school, but the poetic character of blood, that red whisper of life twisting through caverns in the flesh, had intrigued him long before he entered university. And so it was a natural evolution that his scholarly concerns conjoin with his fascination regarding the dragon to create an obsession with Griaule’s blood. It astonished him that no one else had thought to study it. Blood pumped by a heart that beat once every thousand years, never congealing, maintaining its liquidity against inexorable physical logic…the potential benefits arising from such a study were unimaginable. Yet now, peering at the slide he had made, what he saw bore so marginal a relation to human blood, he wondered whether a study would prove rewarding. To begin with, the blood had no recognizable cells. It abounded with microscopic structures, darkly figured against the golden plasma, but these structures multiplied and changed in shape and character, rapidly passing through a succession of changes prior to vanishing—after more than an hour of observation, Rosacher had begun to believe that Griaule’s blood was a medium that contained every possible shape, each one busy changing into every other. He grew fatigued, but rubbed his eyes and splashed water onto his face and kept on peering through the microscope, hoping a dominant pattern would emerge. When none did he was tempted to accept that the blood was magical stuff, impervious to informed scrutiny; yet he was unwilling to let go of obsession, seduced by the infinity of pattern disclosed by the slide, the mutable contours of the mysterious structures, the shifting mosaic of gold and shadowy detail, pulsing as if they reflected the process of an embedded rhythmic force, as if the blood were its own engine and required no heartbeat to sustain its vitality. And such might be the case. No other explanation suited. The matter at issue, then, would be to illuminate the workings of this engine, to discover if its function could be replicated in human blood. He considered going for a walk. Physical activity would allow his excited thoughts to settle and he might then be able to construct an empirical strategy; but he could not pull himself away from the microscope, captivated by the protean beauty of the design unfolding before him, one moment having the smudged delicacy of a rubbing and the next becoming sharply etched against the golden background.

It was apparent that Griaule’s blood contained an agent that was proof against degradation, against the processes of time. Whether this was due to its intrinsic nature or to the enchantment that had rendered the dragon immobile, Rosacher could not speculate; but it occurred to him that the mutable constituency of the blood, the evolution of its patterns, might reflect an ongoing adjustment to the flow of time through matter, an adjustment that prevented it from decaying. This insight seemed not to arise from a process of deduction but from the blood itself, to be basic information carried by its patterns, information that he had absorbed by observing its changes—though to accept such an outrageous proposition was not in his character, Rosacher found he could not reject it. With acceptance came the recognition that the blood might offer not merely an anti-clotting agent, but a remedy to the depredations of time itself and thus to every ill associated with aging. So entranced was he by the flickering mosaic on the slide, he scarcely registered Ludie’s knock.

“Richard?” she called. “Are you there?”

Impatiently, he threw open the door. She wore a petticoat and a frilled bodice, and her kittenish, cocoa-colored face was troubled. He was about to tell her to come back later, when she was pushed aside by a gaunt lantern-jawed man. He towered over Myrie, who peeked from behind him, and was dressed in much the same manner: greatcoat, mud-caked boots, and a slouch hat. His acromegalic features were split by a grotesque smile, brown teeth leaning at rustic angles in the inflamed gums.

“Hello!” he said cheerfully, and clubbed Rosacher in the temple with his fist.

When Rosacher had regained sufficient of his senses to be aware of his surroundings, he discovered that he was trussed hand and foot, and lying on the floor. Ludie huddled beside him and two men—Myrie and the man who had struck him—were ransacking the room, tossing papers and books about, emptying shelves, knocking over his microscope. This abuse caused Rosacher to complain feebly, attracting the notice of the big man. He dropped to a knee beside Rosacher, grabbed him by the shirtfront and lifted him so their noses were inches apart. To Rosacher, dazed, his skull throbbing, that leathery face was an abstract of mottling, moles, and crevices, dominated by two mismatched eyes, one brown, one green—a barren terrain in which two oddly discolored puddles had formed.

“Where’s your money?” the man asked, his rotten breath gushing forth, as from the sudden opening of a stable door.

Rosacher had no thought of lying—he indicated his jacket, which lay across the back of a chair, and watched with muddled despair as the man rifled his wallet. Beside him, Ludie made an affrighted noise.

“This can’t be all!” The big man thrust the few bills he had extracted from the wallet at Rosacher. “It won’t do! Not by half!”

Myrie appeared at his shoulder. “I told you he’d no money, Arthur. It’s his possessions what are valuable.”

“His possessions? This sorry lot?” The big man pushed him away in disgust and, as Myrie fought to maintain his balance, Rosacher thought how strangely genteel a fate it was to be robbed and beaten by two men named Timothy and Arthur.

Myrie, who had fetched up against the workbench, hefted the microscope. “This here’s bound to bring a price!”

Arthur stared at it. “What’s it for?”

“He uses it to look at blood.”

“Blood, you say?”

“It lets him look at it close-like.”

“Oh, well. Now that is a treasure!”

Myrie beamed.

“Yes, indeed,” Arthur went on. “Why we’ll just carry this little item over to Ted Crandall’s shop. Ted, I’ll say, I know you’ve dozens…No, hundreds of people begging for a device that’ll let them look at blood. Close-like!” He gave a forlorn shake of his head. “God help me, Tim. You’re a fucking champion!”

Myrie’s smile drooped; then he brightened and went to the ice chest. “There’s this!” he said, producing the syringe. “He sets great store by it.”

Arthur examined the syringe under the lamp. “This is the blood?”

“I reckon someone might pay dear for it,” Myrie said, and gestured toward Rosacher.

Arthur gazed in disgust at Myrie; without a word, he thumbed the plunger and squirted golden blood onto the little man’s coat. Myrie yelped and flung himself away.

“You brainless ass!” Arthur said, squirting him again. “Dragging me from the tavern for this! I’m marking tonight down. You owe me plenty for this exercise.” He appeared to be on the verge of leaving, but then caught Rosacher’s eye. “What are you looking at?”

Rosacher, not yet up to speaking clearly, managed a perhaps intelligible denial of looking.

“I understand.” Arthur flourished the syringe, which still contained a small amount of the golden fluid. “You’re concerned about the blood.”

“I…” Rosacher hawked up mucus from his throat. “I wish you’d put it back.”

Arthur cupped his ear. “You wish what? I didn’t catch the last bit.”

“The blood will degrade if it’s left out in the air.”

“Too right! We wouldn’t want it to degrade. I’ll put it somewhere safe, shall I?”

Arthur dropped to one knee and gripped him by the throat. An instant later the syringe bit into Rosacher’s left thigh. He cried out and tried to shake free, but Myrie kneeled and pinned his legs as Arthur pushed in the plunger.

The only immediate effect of the injection that Rosacher could discern was a sensation of cold that spread through the muscles of his thigh. Grinning broadly, Arthur dropped the half-empty syringe on his chest and stood.

“Well, now,” he said. “I believe my work here is done.”

He strode to the door and Myrie, after seizing the opportunity to spit in Rosacher’s face, hurried after him.

Ludie came to her knees and began working at his bonds, saying, “They forced me, Richard! I’m sorry!”

She continued to talk, prying at the knots, freeing his arms, his legs, asking if he was all right, her speech muffled as though she were speaking from inside a closet. The numbing cold that had followed the bite of the syringe dissipated and warmth flooded Rosacher’s body, attended by a feeling of glorious well-being. He thought he should sit up, but the impulse did not rise to the level of will. Everything in sight had acquired a luster. Spiderwebs glistened like strands of polished platinum; the boards gleamed with the grainy perfection of gray marble; his broken glassware glittered with prismatic glory, a scatter of rare gems; his possessions scattered across the floor seemed part of a decorative scheme, as if the apartment’s sorry condition were the work of an artist who, guided by a decadent sensibility, had sought to counterfeit shabbiness by using the richest of materials. Ordinarily he thought of Ludie as a lovely girl, but now she struck him as the acme of feminine beauty. Her hair, kept short like a skullcap, gave an elfin look to the clever, triangular face with its sharp cheekbones and large eyes and lips that, due to a slight malocclusion, lapsed naturally into a sulky expression. The hollow at the base of her throat that each morning she sweetened with lime and honey water; her breasts barely constrained by the lacy shells of her bodice…His cataloguing of her physical charms grew more intimate and, energized by arousal, he stood and swept her up and carried her to his bed. Startled by his sudden recovery, she asked what he was doing. He sought to respond, but his thoughts effloresced rather than developing in a linear progression, evolving into elusive, inexpressible logics and fantasies. Touching her skin was like touching warm silk and all the opulent particulars of her body seemed an architecture created to house a central bloom of light. Her anima, he thought. Her spirit. As he joined with her, their flesh glued together in an animal rhythm, he sought that light, plunging toward it, wedding his light to hers in a spectacular union that concluded with a shattering of prisms behind his eyes and a confusing multiplicity of pleasurable sensations that he did not believe were entirely his own.

At long last, leaving her drowsing, Rosacher threw on his trousers, went to the sitting room window and stood gazing out over the rooftops of adjoining shanties and the grander, slightly less ruinous buildings that spread in crooked rows up along the slope of a hill that merged with Griaule’s side. Of the dragon he could see only a great mound of darkness limned by the glow of the newly risen moon. The buildings were picked out here and there by flickering lights, and these lights appeared knitted together by golden lines that formed a constellate shape. Not the predictable shape of a bull or a warrior or a throne, but a complicated mapping of lines and points like an illuminated blueprint. He began to suspect that the pattern they made, like the patterns in Griaule’s blood, contained information that was imprinting itself upon the electrical patterns of his brain, translating its essentials into a comprehensible form. After staring at it for a quarter of an hour he realized that he had the solution to his problems in hand.

It was such a simple answer that he was tempted to reject it on the grounds of simplicity, assuming that a solution so obvious must have flaws—but his only question was whether or not a small dose would produce the same effects created by the massive dose he had absorbed. When he could detect none other, he addressed the ethical considerations. Setting the plan in motion would be an abrogation of his medical oath, malfeasance of the highest order…yet was adherence to an oath more ethically persuasive than funding his research? Toward dawn, the effects of the dragon’s blood ebbing, Rosacher experienced irritability, a symptom such as might attach to a withdrawal; yet this soon vanished, though his feeling of contentment and well-being remained. He wondered if whether the irritability might be due to the size of the dose with which he had been injected. If the blood were not physically addictive, that might be an impediment to his plan. But then he realized that a psychological addiction would be more than sufficient for the purposes. The populace of Morningshade, powerless and possessed of no legitimate prospects, would pay dearly to see their hovels transformed into palaces, their lovers into sexual ideals, and they had no will—none he had noticed, at any rate—to resist temptation, whatever toll it might extract.