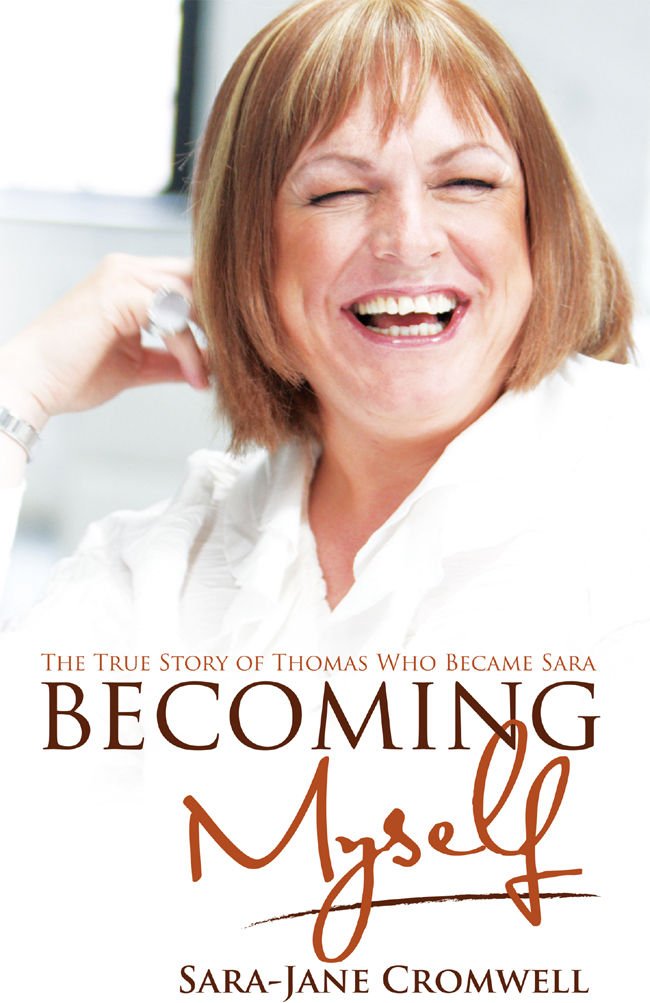

Becoming Myself: The True Story of Thomas Who Became Sara

Read Becoming Myself: The True Story of Thomas Who Became Sara Online

Authors: Sara Jane Cromwell

Becoming Myself

The True Story of Thomas Who Became Sara

Sara-Jane Cromwell

Gill & Macmillan

Contents

Chapter 1: I’m Here, But Who Am I?

Chapter 2: School and My First Jobs

Chapter 4: Puberty: Knowing I’m Different

Chapter 7: The Violation of Purity

Chapter 8: Living Apart, Together

Chapter 10: Everything Changes

Chapter 12: A New Beginning? Maybe

Introduction

The Beginning of the End

There must be a beginning to any great matter, but the continuing unto the end until it be thoroughly finished yields the true glory

[

SIR FRANCIS DRAKE

]

AUGUST 2003

It is a long drive from Cork to Dublin and it is normally a tiring trip, but such was my sense of anticipation and anxiety on that day, I hardly noticed. In fact, the entire trip was no more than a blur. All I could think about was what the doctor would say. I was due to see him at 2 p.m., but he was running late, which made me even more anxious. My chest was tight, I was short of breath and my heart was beating too fast.

I had very mixed feelings about what the doctor was likely to tell me. I wanted him to tell me I was a cross-dresser because that would make my life so much easier, but at the same time I knew I was going to hear the truth spoken for the first time in forty years. I shifted restlessly in the chair in his office, willing him to come into the room. I just wanted him to tell me what was wrong and how to fix it.

For over four decades I had lived a life that felt like a lie; I felt as if I’d been cheated out of life, now here I was, sitting in this chair and waiting for a verdict. This was the moment it all boiled down to: this one particular moment.

Dr Kelly sat back and smiled at me; I sat there as if someone had pressed the pause button. ‘Well, Sara, you probably already know what my diagnosis is going to be. It’s gender identity disorder. I’ll be writing to Dr Donal O’Shea, the endocrinologist at Loughlinstown Hospital to start you on your hormone treatment.’

Gender identity disorder; I hadn’t heard the term until then, but those words would become the defining phrase of my life. Gender identity disorder isn’t about cross-dressing or lifestyle choices or sexuality; it’s a medical condition. In people like me — women born in men’s bodies — the hypothalamus in the brain is formed differently

in utero

and is characterised female. So, while I was born with a male body, I had, to all intents and purposes, a female brain: wrong body, wrong life.

Throughout my life I have tried to feel like a male and live like a male, but I have never believed myself to be a male — even though I have been a son, a brother and a husband. My truth is that I am a female living in a male body, and this little fact has affected every minute of my life until now, and will no doubt do so for the rest of my life, too.

I never asked to be born like this, but I was and I am trying to make a new life for myself. They say a woman should never tell her age, but I am proud of the fact that I have survived against the odds to reach 46 — albeit living the wrong life in the wrong body, just because nature designed me differently.

This story is about what it was like to grow up in the wrong body and to suffer the effects of being different in other ways that many found so unacceptable, condemning me to a life of abuse, ridicule and rejection. But this is also a story of triumph and hope. A story that I hope will inspire others to believe that life really can get better and that it is worth

living, despite all the difficulties. It is a story that shows the importance of being true to oneself, regardless of the price that has to be paid as a result.

For me, there is great solace in knowing I am not alone; we’re not alone. There are countless thousands of people out there who were born different and are living with this, with varying levels of success. This story is dedicated to them. It’s a long story, and although it doesn’t start there, it ends in a place of hope and joy.

Over the past five years I’ve been trying to be myself and to find friends who can love the real me. It hasn’t been the easiest of paths to walk, but it has taught me so much about life and love, about men and women, about hope and achievement. So, this story is the story of my transformation, from a victim of abuse to overcoming that abuse, from false self to true self. That transformation has physical aspects — hormone and bodily changes, hair, make-up, voice — but more important are the changes inside, the changes in my spiritual, inner self. Those are the changes that have given me new ways of thinking and happier ways of being. Those changes allow me to say now, today:

Who am I? I’m Sara-Jane and I’m very happy to be alive, very happy being me, and very happy to meet you.

Welcome to my life!

Part One

Early Days

Chapter 1

I’m Here, But Who Am I?

I do not love him because he is good, but because he is my little child

[

RABINDRANATH TAGORE

]

‘There is something I have to tell you about why I’ve been the way I have been towards you all this time. I always resented you, since you were a baby. I’ve never been able to explain it to myself, but I have resented you and there are times when I still do.’

M

y mother told me this when I was forty-two years of age. Finally, I felt vindicated by the knowledge that I had not been imagining it all these long years. Feeling that she really never loved me and that she really didn’t want me around. The reason why is harder to explain, although I know that at the time of my birth, my mother’s life was far from easy.

Even before I was born, events in my mother’s life were conspiring against her ever wanting or accepting me as one of her own. Like so many other women, she, too, had her dreams and ambitions. And like so many other women at the

time, she had her dreams and ambitions crushed and destroyed. I know that she had a dream of becoming an interior designer, for which she was ideally suited. And no doubt she had a dream of a fulfilling marriage and of raising a healthy, happy family, but this dream was also shattered. These crushed hopes undoubtedly led to great and lasting feelings of disappointment, resentment and bitterness. All of this was crystallised during a series of tragedies which occurred around the time when I was born and I am sure that they contributed to my mother’s resentment of me.

My life started in the Coombe Hospital on 26 June 1960. At least my male life started on that date. When I came into the world, I was given the name Thomas. I was two weeks overdue; a late starter. This late start seems to have been a dominant theme in my life. Apparently, I only came into the world following a scare from a German shepherd dog. My mother opened the back door only to be greeted by a rather enthusiastic dog that jumped at her and scared the living daylights out of her, literally! She went into labour and I was the result.

I’m third in a family of twelve, until recently, seven boys and five girls. But since my diagnosis there are six boys and six girls. It was often said that we were a football team plus one. There were five boys before the first girl arrived. Apparently, being third in line is not the best place to be, especially if you’re the third boy.

I was barely two months old when my mother fell pregnant again and this alone doesn’t bear thinking about. She simply hadn’t the resources to look after three of us, never mind four, but that never mattered in Catholic Ireland of the 1960s. All that mattered was that women accede to the sexual demands of their husbands. They were machines for producing Catholic babies and they did so efficiently and without question.

Women were expected to satisfy their husband’s conjugal needs without any regard to their own or to the dire consequences of constantly producing children for which they could not adequately provide. And if these women failed to satisfy their husband’s needs, well, then they were effectively raped. I did not visually witness such rapes as a child, but I certainly heard them, just feet away from where I slept, and was terrified. I heard my frightened mother plead with my father not to come near her as it was too soon after having yet another baby. Then I heard the smacks and the shouting at her to ‘shut the fuck up!’ Then there was crying, then whimpering, then silence and then the creaking of the bed and then total silence and I went to sleep crying for her. I cry for her now.

Before my parents moved into their new house in Ballyfermot, around the time when I was born, they had lived in married quarters in McKee or Collins Barracks, as my father was in the Army Motor Squadron and later joined the military police. And it was here that they were to experience some of the most traumatic events of their lives.

My father was staying in McKee Barracks the night before he was due to fly out on a tour of duty to the Congo with the United Nations. On that fateful day my mother learned that a man who had raped her some years earlier had moved into the neighbourhood. Not surprisingly, she had a breakdown, putting her hands through the glass window of our front door. My father was called home to take care of her and she was taken to St Loman’s Hospital. As a consequence, my father’s best friend was sent to the Congo in his place.

This friend would be killed, along with nine others, during a massacre at Niemba in September 1960, barely three months after I was born. It is almost impossible to imagine

the impact this must have had on both their lives. They also knew some of the other soldiers killed, which only served to multiply their sense of loss and sorrow.

It is hard to think that they did not blame themselves in some way for their friend’s death and that they were not wracked with guilt for a long time after the event. I know for certain that my mother attributes these events and others for causing my father to ‘go off the rails’; what we now know as post-traumatic stress disorder. Of course, such a diagnosis did not exist then and those suffering from the condition received absolutely no help whatsoever. She assured us that our father was not always the violent man we knew him to be while growing up; that in fact he had been a very different man before these tragic events occurred.

I can say with a high degree of certainty that the difficult relationship that developed between me and my mother has its roots in this particular period of time. Although I find her animosity towards me, that bordered sometimes on hatred, difficult to understand. I remember a woman who made it abundantly clear that she did not want me and did not love me and is best summed up in her own words and through gritted teeth: ‘I had twelve mistakes and you were my biggest mistake of them all!’ In her bitterness and disappointments, she was all too human and imperfect, just like the rest of us.

My father remains something of an enigma to me and, like my mother, I feel that I hardly know him at all. I never had the kind of relationship with him that would allow me to get to know him better. What I do know about his earlier life comes from my mother and one of my brothers. He came from County Louth and had three other brothers that I know of. From what I’ve learned, he also had a terrible life: he was

sexually abused while growing up and had more than his fair share of brutal beatings.

He spent long periods abroad on

UN

duty and when he was home, he was in the Curragh or on weekend camps with the army. When he wasn’t away with the army, he was working on nixers for the owner of the local pharmacy. If he wasn’t working outside the home, then he was working at home, painting, wallpapering and building the kitchenette, which I helped him to build. At one stage, he left the army for a number of years and went to work in a local weaving factory, where I went to work some years later. I used to bring him his lunch while he was at work and remember being overawed by the size of the machines and the noise they made. And the fluff! He eventually went back to the army and joined the military police. I always associated his uniform with aggression and violence and of being told what to do without the right to speak up. Unlike many men of his time, he was not much of a drinker and rarely, if ever, smoked, though later on he smoked a pipe. This gave him an air of calm which I rarely ever experienced.