Bedouin of the London Evening (2 page)

Read Bedouin of the London Evening Online

Authors: Rosemary Tonks

Wedding picture (

from left to right

): bridesmaid cousins Wendy and Jill, pageboy Tim, Michael (Micky) Lightband, Rosemary. Holy Trinity Church, Brompton, London, 21 January 1949.

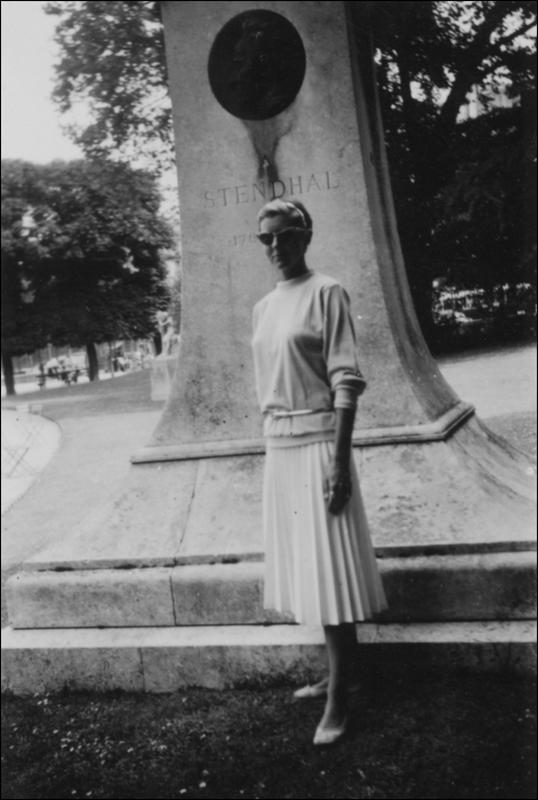

Rosemary in the Jardin du Luxembourg, Paris,

c

. 1952-53.

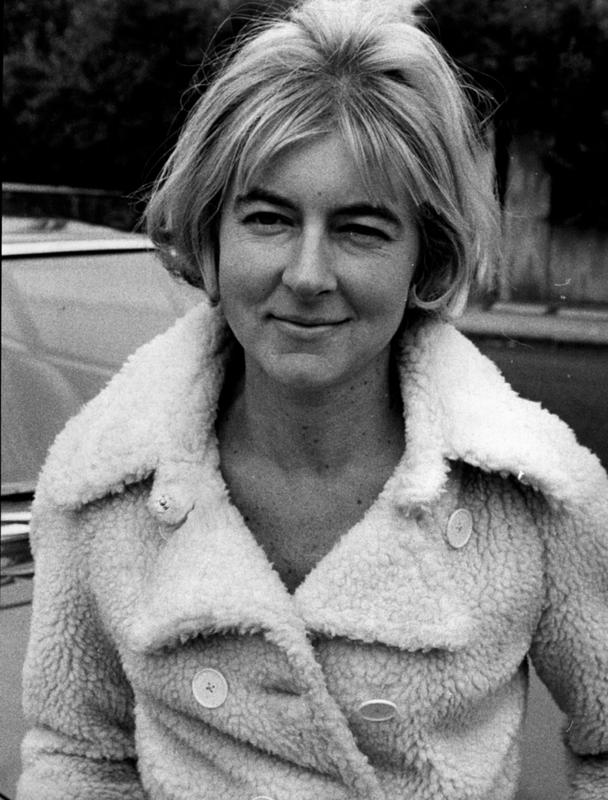

Rosemary Tonks, London, 1969

(photo: Associated Newspapers/REX)

One of very few other published women poets of that time, she wasn’t, however, noted for supporting the sixties sisterhood, being taken to task by Jane Gapen in the

New York Review of Books

for an unsympathetic review (p.117) of Adrienne Rich’s

Diving into the Wreck

, which ‘should be reviewed from a feminist outlook… It really hurts that a woman would say this about another poet.’

27

Nor did she feel connected with other poets. ‘They are a rather lost set, you know, in London,’ she told Peter Orr in 1963. ‘They form movements.’ (p.109) However, she did form close relationships with both Robert Conquest, the Movement’s anthologist, and poet and novelist John Wain. Philip Larkin admired her work, and corresponded with her

28

when editing his

Oxford Book of Twentieth-Century English Verse

(1973), resisting her suggestion that her poem ‘Love Territory’ (p.39) would represent her better than one of his eventual choices, ‘Story of a Hotel Room’ (p.62) and ‘Farewell to Kurdistan’ (p.97).

Geoffrey Godbert recalls meeting her at gatherings of the Group at Edward Lucie-Smith’s Chelsea house in the 1970s: ‘She immediately gave the impression of a coiled spring waiting and needing to be unsprung. Surrounded by the voices of conventional wisdom, she manifested the loner’s stare into, and the need to speak of, the indescribable future before it was too late.’

29

Anthony Rudolf met her a few times in the mid sixties at the house of their onetime patron, Miron Grindea: ‘She was a forceful

personality and I recall an argument we had in the presence of Pablo Neruda in Grindea’s legendary salon. Her poems matched the forceful personality, being rhetorically explosive, with more exclamation marks than anyone else used.’

30

John Horder also recalls how she ‘spoke with an intensity bordering on active aggression’.

31

Re-reading Rosemary Tonks’s work, and talking and corresponding with family and others who knew her, traits soon become apparent which connect the outspoken and uncompromising writer who had no truck with politics (in the novels) or feminism, and was dismissive of any poet whose work she felt lacked integrity or authenticity, with the single-minded born-again Christian convert, the later Mrs Lightband. Despite the divorce she never wanted and could never forgive him for, she kept her ex-husband’s name – needed for the new identity – and cut off anyone else in her family who divorced, regardless of fault, including one cousin who had always been dear to her.

The poems are full of damning judgements, insults, extremes, resentments, betrayals and irreconcilable opposites. She writes of her ‘intolerance’, of being ‘powerful, disobedient’, and of leading her ‘double life among the bores and vegetables’. In ‘Diary of a Rebel’ (p.44), she needs the café for her ‘fierce hot-blooded sulkiness’; in ‘Poet as Gambler’ (p.67), ‘gutter and heavens’ were her lottery in a ‘wasted youth’; in ‘Running Away’ (p.40) she tears up ‘the green rags of the Bible’: ‘I left the house, I fled / My mother’s brow where I had no ambition / But to stroke the writing / I raked in. / […] I was a guest at my own youth; under / The lamp tossed by a moth for thirteen winters.’

The younger Rosemary comes across as headstrong, wilful, stubborn, obsessive, rebellious, judgemental, fiercely intelligent, and given to extreme ways of thinking. Growing up a widow’s only child during the 1930s, packed off to boarding school before and during the war, she was disconnected from other people: ‘For this is not my life / But theirs, that I am living. / And I wolf, bolt, gulp it down, day after day’ (‘Addiction to an Old Mattress’, p.91). Much of her fiction also shows a similar sense of disconnection,

with other characters perceived as separate from a witty narrator or protagonist, or even observed from some distance as in the short story ‘The Pick-up or L’Ercole d’Oro’ (p.137). Looking back in her 80s, trying to make sense of her upbringing, she noted: ‘No sense of self’.

32

The last review she published was a long essay on Colette in the

New York Review of Books

(p.127), parts of which read uncannily like versions of her own plight (except that both parties in her own marriage had apparently been unfaithful):

[Colette’s] childish idea of herself had run on unchecked after marriage, and Willy had fostered it; in fact it was

all she had

. Suddenly she found out that he was unfaithful. The shock to her ego was more than it could bear; there was nothing inside capable of withstanding the blow, her personality was fragmented, and she collapsed into a nervous breakdown. At that moment she lost her childhood, and no longer knew who she was. […] When it was all over, and as soon as she began to write the first

Claudine

, she found herself, and could repair her identity. But this time a new self was in charge. It prescribed physical exercises for her body, and undertook the task of learning how to think, and

be

; the spirit stopped still and listened – an Oriental skill.

During her childhood, her widowed mother had sought guidance from mediums, and Rosemary thought her mother’s life and her own had been harmed by their self-fulfilling prophecies as well as by the church. Like her mother, she was superstitious, but took this to an extreme, believing in signs and omens that showed the presence of evil spirits. There was cause and effect in supernatural occurrences, and she came to see almost everything in life as black or white, good or evil.

The sudden death of her mother Gwen in a freak accident in the spring of 1968 precipitated a personal crisis. Believing the church had failed her ailing mother when she’d most needed its help, Rosemary turned her back on Christianity, and for the next eight years attended spiritualist meetings, consulted mediums and healers, and took instruction from Sufi “seekers”. The inspiring presence

in her house of a collection of ancient artefacts, including Oriental god figures, led to her approaching a Chinese spiritual teacher and an American yoga guru. All these she repudiated in turn.

Following the collapse of her marriage, she entered the solitary later phase of her life. By 1977 she was living just a few doors away from her ex-husband (soon to be joined by a new wife) on Downshire Hill, doing Taoist meditation, writing reviews and working on a new novel. But other misfortunes followed: a burglary in which she lost all her clothes; a law-suit costing thousands of pounds; and ill-health, including incapacitating neuritis in her one good arm.

Rosemary attributed her next life disaster to her difficult Taoist eye exercises, which involved staring for hours at a blank wall, turning the eyes in and looking intensely at bright objects. On the last day of December 1977, she was admitted to Middlesex Hospital for emergency operations on detached retinas in both eyes, which saved her eyesight but left her nearly blind for the next few years. This was her reward for ‘ten long years searching for God’. Unable to see properly, emaciated and ‘psychologically smashed’, she couldn’t cook or shop, and rarely left home. Following a whole series of personal crises, this isolating experience of near-blindness which continued with only minimal improvements over many months must have been traumatic, with the sensory deprivation involved possibly helping to trigger a gradual shift in her mental state.

33

She had been discussing – since November 1976 – the publication of a selection of her poems by John Moat and John Fairfax’s Phoenix Press in Newbury. This was to include 34 of the poems from her two collections from Putnam and Bodley Head, both publishers having first declined to release paperback editions after the hardbacks had sold out, before stopping publishing poetry altogether: ‘Which is the reason I am landed as I am,’ she wrote to John Moat.

34

In August 1977, she commented:

Some of these poems will need revision. I know what’s wrong; it will take a few days.

The poems go into 4 categories. Travel, the Life, Love, Early Youth. I’ll come up with a special title for the book. Titles are most important. If I

do

finish the novel on time, then I will indeed compose a new poem – it used to take me up to 2 months. (Long ones 3 months) I have a bundle of notes sitting here waiting, but then so does the bill for rates, and although I am financially OK at the moment I’m concerned to be able to maintain my way of life into the future and until death. No one’s going to pay me for writing poems!

35

But there were to be no more poems (or revisions). By July 1978 she was still struggling to recover from her ordeal:

I’ve had the most tremendous fight, month after month

alone

, to get back sight to what it was before op. I shall make it, with God’s help. Am doing it – or rather

He

is. The thing is that I am worn down & so weak & wasted by the struggle that everything is the most terrible effort. And it has to go on – as this thing takes months to heal, a friend tells me. […] I cannot work on the poems at moment, I can just about write this letter. […]

You could publish them as they are, uncorrected by me.

But

they will have no support (from novel & other books in preparation) & will sink like a stone & be lost all over again. By the

autumn

/winter I should be able to get the novel to my agent.

36

Her struggles continued. Writing a year later:

The thing is that I am still fighting for my eyes.

At last

something is happening. I am keeping a record: it is incredible. Everything is agony, you see. Last year just having them open was agony – & couldn’t see when they were. Now it seems a door might have opened for me: I am getting discharge from both eyes, and a hundred other things. I am being healed. […]

I plan to spend the winter at my aunt’s, very slowly correcting my big book.

37

Later that autumn she left London for Bournemouth, given refuge at her aunt Dorothy’s flat, where again she looked for help from spiritualists – this time Charismatics and Pentecostalists –

before coming to the realisation that her own spiritual truth lay only in the Bible itself, especially the New Testament, the first book she was able to read as her sight began slowly to return, albeit imperfectly.

Deciding to settle in Bournemouth, she tried for several months during 1980 to sell her London house, but each time a buyer turned up the sky would darken and there would be a foul smell in the house. This happened so often that she ruled out coincidence. She cleaned every room obsessively and threw out all her books on spiritualism and the occult, all to no avail. Finally, believing that the Oriental religious artefacts that filled the house must be exerting some malign power, she packed them all into five suitcases and got help to have them deposited in the vault of Barclays Bank in Hampstead. She saw these as sinister objects, stolen from temples and graves, which had led her to seek knowledge of God through what she now believed to be a diabolical Eastern religion. The very next day a young couple came to see the house in bright sunshine, loved it and bought it.