Beethoven: Anguish and Triumph (100 page)

A coy transition from the introduction leads into the first-movement Vivace, quiet at first but with mounting excitement. The Vivace is a titanic gigue. This is Beethoven's third symphony in a row whose first movement is dominated by a monorhythm. Its dotted figure is as relentless as the Fifth Symphony's tattoo, as mesmerizing as the Sixth's loping rhythms, but now the effect is propulsive and intoxicating rather than fateful like the Fifth or gentle like the Sixth. Rhythm plays a more central role than melody here, though there is a piping folk tune in residence. The second theme amounts to a passing interlude before the first theme is picked up again. The development proper has no real theme at all; it's scales, arpeggios, and rhythm. The music is steadily engaged in its quick changes of key in startling directions, everything propelled by the élan of the rhythm. From the first time one hears the symphony one never forgets the lusty and rollicking horns, which at the time were valveless instruments pitched high in A. Low, epic basses and shouting horns: these are the distinctive voices in an orchestral sound more massive and bright than in any of his earlier symphonies (each with its own orchestral color).

Also few listeners forget the first time they hear the stately and mournful, sui generis dance of the second movement, in A minor.

16

It was a hit from its first performance. Here commences, as much as in any single piece, the history of Romantic orchestral music. The idea is a process of intensification, adding layer on layer to the inexorably marching chords in the low strings (with their poignant mix of major and minor) until the music rises to a sweeping, sorrowful lament. Once again, in a slowish movement now, the music is animated by an irresistible momentum. For contrast comes a sweet, harmonically stable B section in A major (plus C major, a third up). Rondo-like, the opening theme returns in variations, lightened, turned into a

fughetta

, the last variation serving as coda.

17

The scherzo is racing, eruptive, giddy. Its main theme, beginning in F major and ending up a third in A, from one flat to three sharps in a flash, echoes harmonic patterns set up in the first pages of the symphony. The music is back to brash shifts of key animated by relentless rhythm. The trio, in D major (a third down from F), provides maximum contrast, presenting a kind of majestic tableau around an A drone, frozen in harmony and gesture like a painting of a ballroom. The trio returns twice and feints at a third time before Beethoven slams the door.

The intention of the Allegro con brio finale is to ratchet the energy higher than it has yet been. Few pieces attain the brio of this one. If earlier we had exuberance, stateliness, brilliance, those moods of dance, now we have something on the edge of delirium: a stamping, whirling two-beat reel, with the horns in high spirits again. Does any other symphonic movement sweep listeners off their feet and take their breath away so nearly literally as this one? Perhaps the most intoxicating moment in the finale is the closing section of the exposition in C-sharp minor, with its natural-minor B surging against the simultaneous harmonic-minor B-sharp. The symphony ends with the horns shouting for joy.

Among musicians the Seventh became famous for the daring and freshness of its modulations and the unity of its key scheme with its chain of thirds, C, A, F, and D major the central ones. Beethoven always had reasons for his keys in a piece, and this is one of his most subtle. Those four tonalities are chosen not just to make a dazzling effect. The keys C, A, F, and D major have

three and only three notes

in common:

A, D, and Eâthe tonic, subdominant, and dominant notes of A major. Which is to say that Beethoven made his central complex of keys related by thirds into a symphonic expansion of the three most important notes in his home key of A major.

18

(Whether by coincidence or design, E, D, and A are also the first three downbeat notes in the

vivace

theme of the first movement.)

Among Beethoven's symphonies, the Seventh also marks the point when he largely left behind the heroic style and ethos. It is his first symphony since the Second to have no overt sense of dramatic narrativeâsomething he was also slipping away from. Instead of narrative unity there is a unity of theme: the moods of dance.

19

One senses the influence of Beethoven's folk-song settings on the piece, including the “Scotch-snap” rhythm in the first-movement theme. More specifically, the main theme of the finale echoes his arrangement of the Irish tune

Nora Creina

that he made for Thomson. At the conclusion of that 6/8 folk tuneâas much fiddle tune as songâBeethoven added this tag of his own:

Â

Celtic Elements

Â

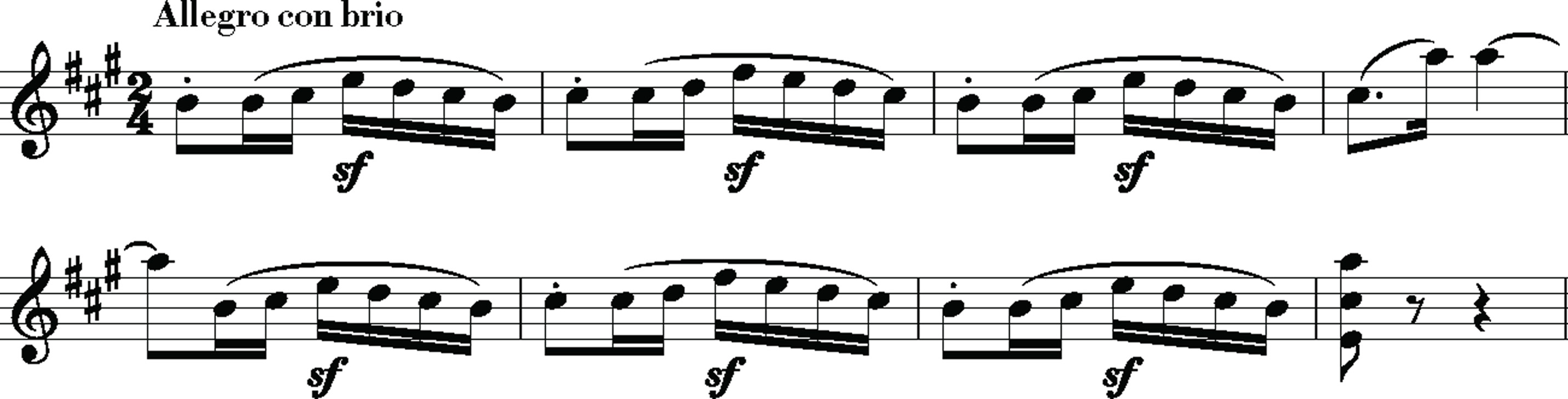

For the finale of the Seventh he turned that idea into 2/4 to make his main theme:

Â

Â

So the dozens of folk tunes Beethoven was “scribbling”âhis termâin those years to pay the rent were also, surely as he hoped, turning out to be useful in his more ambitious music. Of course, for an artist anything is potential material: an emotion felt or endured, a book read, a person or a tune encountered, suffering emotional or physical.

The premiere of the Seventh and

Wellington's Victory

under Beethoven's baton was one of the most triumphant moments of his career before the public. For the first of many times, the audience demanded an encore of the slow movement of the Seventh. The orchestra was fiery and inspired, suppressing their giggles at Beethoven's antics on the podium. The paper reported from the audience “a general pleasure that rose to ecstasy.” By popular demand, the concert was repeated four days later, with Maelzel's mechanical trumpeter again on hand. The celebratory music played into the celebration of Napoleon's fall and hopes for the end of so many years of war. The Seventh went on to become one of the most popular items in Beethoven's portfolio, issued in transcriptions for everything from two pianos and piano four hands to string quartet, piano trio, winds, and septet.

20

The two performances garnered 4,006 florins for wounded veterans.

21

Beethoven sent a copy of

Wellington's Victory

, with its hallelujahs for England and the king, to the prince regent in England with a dedication, hoping the future king would respond generously.

22

True, the trashy and opportunistic

Wellington's Victory

got the most applause. It also set the tone of much of the music Beethoven was to write in the coming months. No amount of success could save him from rankling illness and creative uncertainty. Nor did the Seventh make clear the new path he was searching for. But for the moment he was not too proud to bask a little, to look forward to handsome proceeds from his own benefit concerts, even to enjoy with a sardonic laugh the splendid success of the bad piece and the merely bright prospects of the good one. The Seventh Symphony after all celebrates the dance, which lives in the ecstatic and heedless moment.

Â

Beethoven told Goethe he believed that artists mainly want applause, and he was receiving extraordinary applause these days. It hardly lightened his mood. Soon after the triumphant charity concert he wrote yet another lawyer yet another rant about the stipend and the detestable Viennese and, for good measure, his brother Carl, over an issue that is not recorded:

Â

Many a time indeed I have cursed that wretched decree for having brought innumerable sorrows upon me . . . the best course would be to hand in the application first to the Landrechte [the court for the nobility]. Please do your share and don't let me perish. In everything I undertake in Vienna I am surrounded by innumerable enemies. I am on the verge of despairâMy brother, whom I have loaded with benefits, and owing partly to whose deliberate action I myself am financially embarrassed, isâmy greatest enemy! Kiss Gloschek for me. Tell him that my experiences and my sufferings, since he last saw me, would fill a

book

.

23

Â

Around the same time, he wrote his old patron and delinquent stipend contributor Prince Lobkowitz, then the object of some of his legal initiatives, “The profound regard which for a very long time I have sincerely cherished for Your Highness, has in no wise been affected by the measures which dire necessity has compelled me to adopt.”

24

In Beethoven's recent letters to others, Lobkowitz had been the “princely rogue” and “Prince Fizlypuzly.”

25

Lobkowitz had known Beethoven long enough not to expect much gratitude.

Right after the premieres Beethoven got busy producing another concert, this one for his own benefit, in the large

Redoutensaal

of the Hofburg. It was to include a dramatic coup in the style of

Wellington's Victory

. “All would be well,” he wrote Zmeskall, “if the curtain were there, but without it

the aria will be a failure

. . .

Without a curtain or something of the kind its whole significance will be lost!âlost!âlost!

. . .

The Empress has not said yes

[to attending]

but neither has she said noâCurtain!!!!

” For this concert of January 2, 1814, Beethoven included a bass aria from

The Ruins of Athens

. At the end of the aria a curtain was to sweep aside revealing a bust of Austrian emperor Franz I, the effect sure to bring down the house. The benefit repeated

Wellington's Victory

, already a sensation in Vienna.

This time Beethoven's berserk conducting nearly ran aground because he could hear so little of what he was directing. The orchestra had gotten used to the idea that he was going to swell up in the loud passages and more or less disappear under the music stand in soft ones. But when he got lost and jumped up at a soft moment and sank to his knee at a loud one, confusion and hilarity threatened. House

Kapellmeister

Michael Umlauf, prepared for this sort of thing, stepped behind Beethoven and restored order. When Beethoven realized the orchestra was not following him anymore, it is reported that he produced a smile. Amused? Embarrassed? Horrified? After the concert he placed a notice in the newspaper thanking “the most admirable and celebrated artists of the city” for their contribution to a splendidly successful evening.

26

Among the listeners at the concert was young violinist Anton Schindler, who met Beethoven this year when he delivered a note from violinist Ignaz Schuppanzigh. They met occasionally in the next years. It is not clear at what point Schindler determined to make a career out of his connection to the great man, to become what Beethoven called “an importunate hanger-on.”

27

This last concert produced considerable proceeds and inaugurated what in financial and critical terms became the most profitable year of Beethoven's life. The immediate practical result was that three singers from the court opera approached him about a revival of

Fidelio

, and George Friedrich Treitschke, manager of the Kärntnertor Theater, signed on to the idea. Treitschke had seen the first version, had been part of the group who pressured Beethoven to do the initial revision. Beethoven agreed to the revival but insisted on making many changes first, with Treitschke's help.

28

This time he found the ideal collaborator. Treitschke was a man of the theater; he had begun as an actor and went on to be a playwright and manager.

29

As usual the project mushroomed and became another cross for Beethoven to bear, but the results for his orphaned opera were enormous. At least now there appeared a detectable lightening in his mood. He wrote his friend Count Franz Brunsvik in Buda of the recent successes, declaring, “In this way I shall gradually work my way out of my misery . . . My opera is also going to be staged, but I am revising it a good deal . . . As for me, why good heavens, my kingdom is in the air. As the wind often does, so do harmonies whirl around me, and so do things often whirl about too in my soul.”

30