Beethoven: Anguish and Triumph (115 page)

Â

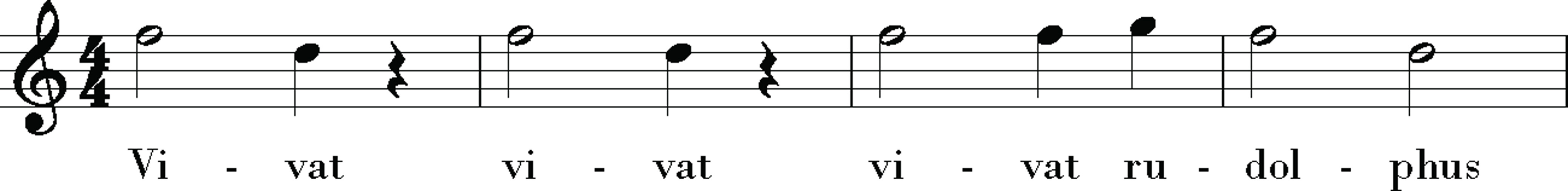

That fanfare seems to have begun as a sketch for a choral salute to Archduke Rudolph; proclaiming “Vivat Rudolphus!,” it resembles the sonata's opening:

Â

Â

The phrase does not survive in the music, but the

vivat

quality does. From the outset the sonata was intended to be dedicated to Rudolph and presented to him on his name dayâbut like most promised Beethoven works now, it was not finished in time.

38

The dialogue of the first movement is between those initial gestures: full, heroic, and declamatory versus sparse, flowing, and contrapuntal. In the development section, the counterpoint blossoms into a stamping and pealing fugue. Here as in all his last sonatas he folds Baroque fugue into the modern structure of sonata form.

The particular tone of this movement and the

Hammerklavier

in general has little to do with the kind of implied narrative in instrumental music that was once a Beethoven staple. The first movement is not “expressive” in the usual sense, more a matter of indefatigable energy (all of it seriously fatiguing for the pianist), sometimes hard-edged and sometimes soaring. The singular world of the piece comes from its particular obsession, its way of joining content and form, microcosm and macrocosm. The opening

vivat

rhythm will be varied and fragmented throughout, as usual in Beethoven. In measures 2 and 4, the two sharp strokes of descending thirds, DâB-flat and FâD, will have their consequences, as also expected. It is the breadth and depth of those consequences that were new in Beethoven and new in music. This time those little melodic thirds are going to resonate at every level of the piece, governing the construction of themes, the harmonic sequences small and large, the sequences of keys, the keys of sections and movements. Instead of narrative in the outer movements, there is a depth of unity that goes beyond older conceptions and brushes aside centuries of tradition concerning key relations.

39

To a degree, in this sonata Beethoven obliterated the old dichotomy between melody and harmony: melody traditionally based mainly on scales, harmony on larger intervals that form chords. Here melody and harmony merge.

More than ever for him, from now on each major piece will be founded not on a novel formal or dramatic idea but on a rethinking of the nature of music and its genres, a search for fresh qualities and meanings that in turn reshapes the old formal models in more and more radical waysâwithout ever entirely departing from those models.

40

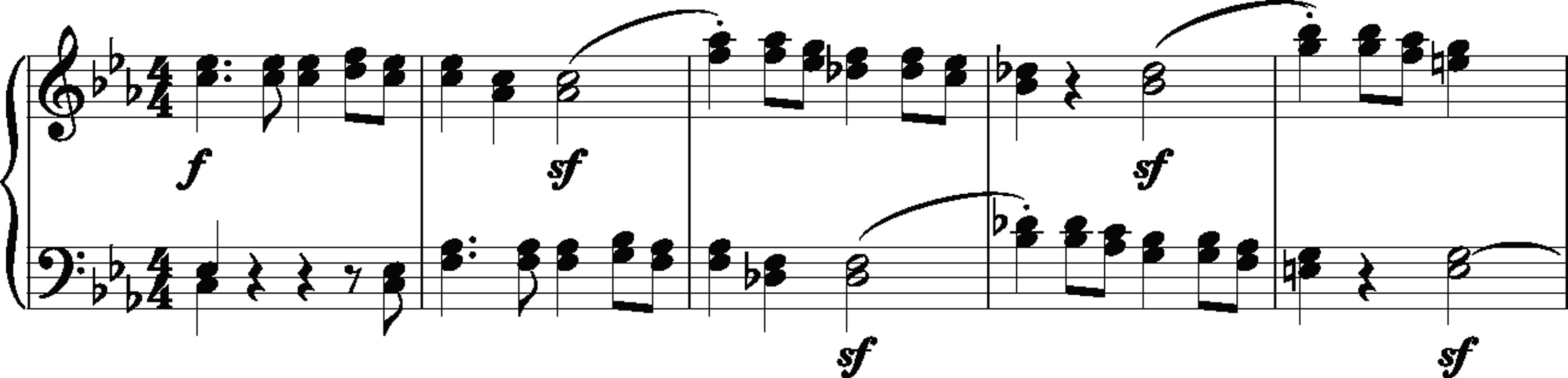

In this case, technique spills over into metaphysics. One ancient and abiding theory of the universe is that the smallest structures expand, level by level, into the largest. That is how the

Hammerklavier

works. Every melody in the piece is based on a scaffolding of descending thirds. The keys of the large sections in the first movement trace a descent in thirds: B-flat first theme, flowing second theme in G major, development beginning in E-flat. The fugue in the development section, its subject based in the

vivat

figure, marches downward athletically in thirds, sometimes in parallel-third lines:

Â

Â

Meanwhile, a modulatory scheme based on chains of thirds is theoretically endless. In contrast to the usual tonicâdominantâtonic closed system of diatonic music, it creates an open system that can conjure either gentle wandering or irresolvable tension. In the

Hammerklavier

, Beethoven exploits both those possibilities.

In the central part of the first movement, the Baroque procedure of

fugue

is wedded with the Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven idea of

development

. The counterpoint of the development flows on into the

vivat

recapitulation and its answer, decorating them both. The end of the movement adds another element in the form of sustained trills; in the finale, trills are going to add a steady sparkle to the texture. The last moments form a giant stride of the

vivat

figure from nearly the top of the keyboard down to nearly the bottom.

Following the massive landscape of the first movement, a succinct scherzo, also in B-flat, takes up the

vivat

idea of that movement and turns it into light, lilting comedy. The form is entirely regular, on the old model of the minuet-scherzo. Its trio is a rolling B-flat-minor episode, Romantic unto bardic in tone, that foreshadows the next movement. With a scale that sweeps across the keyboard from bottom to top and a little giggle, we return to the scherzo proper.

After the comedy comes the tragedy, the longest slow movement Beethoven ever wrote, marked Appassionato e con molto sentimento, impassioned and with great feeling. The movement is in F-sharp minor (a third down from B-flat) and sonata form, but it feels like an endless song that encompasses the whole of a person's feeling life.

41

The music is constantly in evolution, like drifting through an endless dreamscape of sound and emotion. At the beginning it is marked

una corda

, meaning the muted effect of the hammers on one string, done with the soft pedal.

42

The second half of the first theme returns to

tre corde

, marked

con grand' espressione

, “with great expression.” If it had been written for the stage it would be called one of the great tragic ariasâexcept it is an aria only the piano can sing. In its course there are magical moments of G major that appear like sunlight breaking through clouds.

In Beethoven's work the harbinger of this movement is another minor-key slow movement he wrote in a piano sonata, the D-minor lament in op. 10, no. 3âa work that like the

Hammerklavier

juxtaposes a comic movement with a tragic. As man and composer Beethoven had learned a great deal since op. 10, much of the human wisdom having to do with suffering. This movement laments and transcends the lamentation in the singing, above all at the recapitulation, where the theme is ornamented into spinning roulades like streams of tears. The slow movement of op. 10 sounds like sorrow itself; the slow movement of the

Hammerklavier

sounds like a sublime performance of sorrow and transcendence by a singer who has known every shade of grief and hope.

After Beethoven mailed the

Hammerklavier

to Ferdinand Ries in London, he sent an addition to the slow movement, a simple rising third, AâC-sharp, in octaves for the beginning, a one-bar introduction. Looking at it, Ries recalled, he wondered whether his old master had finally gone around the bend. Then he played it and discovered how those two notes color the whole of the gigantic movement. Like all great Beethoven, here are technique and expression joined: the added introduction is there partly to remind our ears of the primal significance of thirds in the sonata. The slow movement now begins with a simple gesture that is the distilled essence of the whole piece.

Like most of his late works, the

Hammerklavier

is aimed toward the finale, which is a prodigious fugue. But there needed to be a transition from the mournful canvas of the slow movement to a finale that takes up and pays off the dynamic energy of the first movement. For a solution Beethoven turned to tradition and in the process wrote one of the most striking pages of his life. The introduction takes up the old practice of preluding, in which an improviser plays free, drifting music figuratively or literally in search of an idea. To evoke that sense of protean exploring, Beethoven largely leaves out bar lines and erases any sense of beatâlike some Baroque preludes. Within that freedom, a chain of thirds slowly wends its way downward through harmonies and keys until it reaches F, preparing the B-flat-major finale.

In the middle, when the chain reaches B major, there is a Bachlike eruption of imitative counterpoint that just as suddenly vanishes. Here is another feature of Beethoven's late music:

music about itself, a querying and questing evoking its process of being composed

. Now a question is posed: “How shall I write the fugue?” The prelude to the finale is an evocation of a composer searching for material, seizing on something and dropping it almost with a shake of the head, continuing the search until the solution is found (the finale of the Ninth Symphony will return to that notion). Much of the

Hammerklavier

has that quality of self-reflection, music observing and commenting on itself in the process of its unfolding.

So one of those as-if comments in the introduction is on the idea of fugue, which turns out to be what the prelude was searching forâprefigured by its abortive burst of Bachlike counterpoint. (For models, Beethoven copied out bits of fugues from

The Well-Tempered Clavier

alongside sketches for the finale.)

43

What is rejected at that point by the symbolic composer is not Bach or counterpoint but

old-style

counterpoint.

44

“The imagination, too, asserts its privileges,” friends reported Beethoven saying, “and today a different, truly poetic element must be manifested in conventional form.”

45

Form informed by poetry

. He had begun thinking of his music in poetic terms. He wanted more feeling and evocation than drama and narrative. In keeping, he took to calling himself a

Tondichter

, tone poet, rather than a

Komponist

. In his always laconic comments on his music he spoke less of Aufklärung

reason

, more of Romantic

imagination

,

reverie

, and the like.

46

As his words to and about Goethe show, he believed poets to be the most significant of artists.

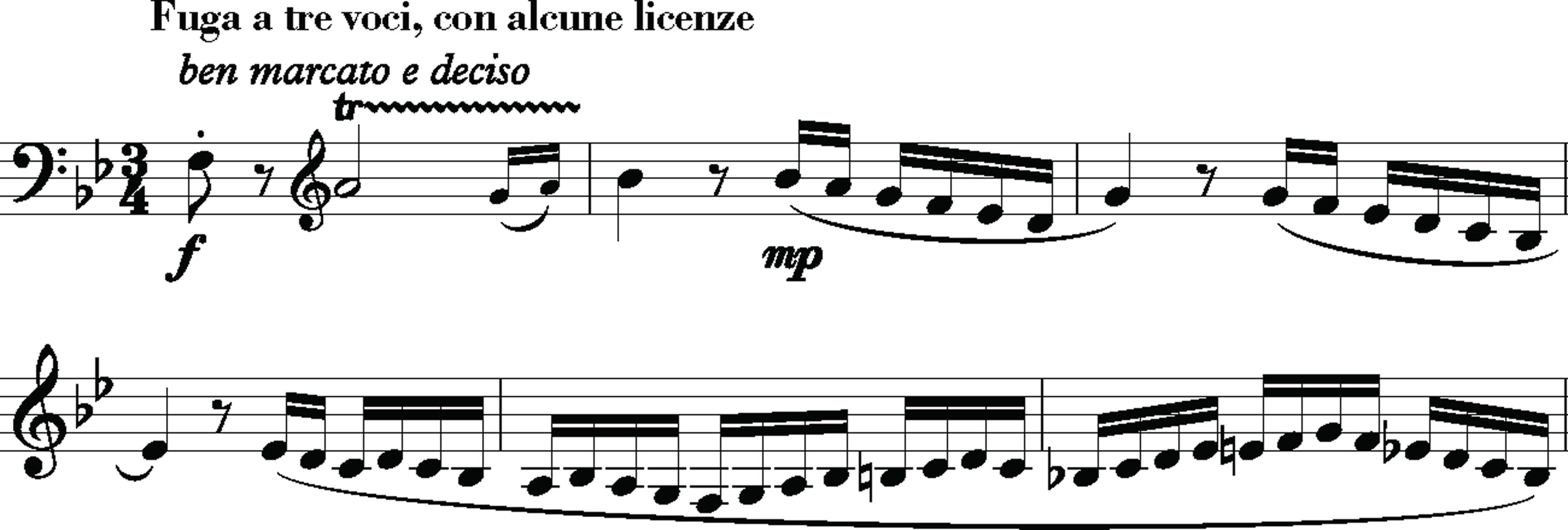

So for this fugal finale, involving that familiar Baroque genre, he intended to make something new, poetic, both Bach and not-Bach, starting with its long, amorphous, quite outlandish subject. Its primal features are a giant leap up of an octave and a third, a trill, and a babbling chain of sixteenths:

Â

Â

What happens to that theme in the course of the movement is going to spin out in two virtually contradictory directions. The fugue subject is treated to the old contrapuntal procedures of augmentation (stretching it out), inversion (turning it upside down), retrograde (backward), and stretto (theme entering on top of itself), all carried forth within the traditional outlines of fugal exposition and episode, subject and countersubject(s). At the same time, motifs from the subject are spun off as material for thematic variation and development, those sonata-like elements subsumed within the fugal texture. He pursues, in other words, a melding of apparently mutually exclusive genres, fugue and sonata. That serving of two masters at once is what creates some of the overheated quality of the music.

The keys of the finale's seven large sections form another descending chain of thirds: B-flat majorâG-flat majorâE-flat minorâB minorâG majorâE-flat major. At that point, the music moves down a step to D major, from there falling a third to B-flat major in the return to the opening theme. This kind of complex and systematic modulation defining the sections of a piece is something sonatas can do that Baroque-style fugues do not. In other words, the fugal treatment is obsessively technical at the same time that the audible effect is of rhapsodic freedom.