Beethoven: Anguish and Triumph (152 page)

Â

The preceding are the main forms used in multimovement symphonies, concertos, solo sonatas, string quartets, and other chamber music. The overall idea has to do with contrasts of mood and tempo: a typical work might have a fast first movement in sonata form, a slow movement in ABA form, a medium-tempo minuet or racing scherzo, then a fast finale in sonata-rondo form. This pattern was, like all else, infinitely variable. Here and there in his work, Beethoven created new ad hoc or hybrid forms, such as the finales of the Third and Ninth Symphonies.

Â

FUGUE

Â

Fugue

is a contrapuntal procedure that evolved in the early Baroque period and persisted through the Classical period and later. First, recall what

counterpoint

is: a superimposition of melodies, each line (called a

voice

, even in instrumental music) its own melody, yet the whole also creating effective harmony. (This is in contradistinction to other kinds of texture that involve a single melody with accompaniment.) In the Classical period and later, although fugues were still often composed, the idea had become a kind of self-conscious archaism. Because achieving a balance of good melody and good harmony in counterpoint is one of the most difficult skills in composition, usually involving concentrated study to master, the Classical period called fugue and overt counterpoint “the learned style.”

A simple fugue is based around a single melodic idea called the

subject

. Counterpoint is woven around that subject, sometimes involving a consistent second thematic idea called a

countersubject

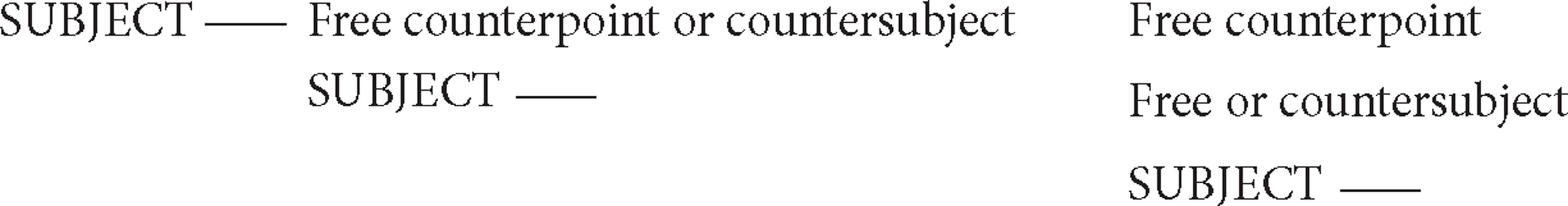

. A typical fugue begins like this: the subject is heard alone, then a second voice enters on the subject in the dominant key while the first voice continues in counterpoint (perhaps that being the countersubject); then a third voice enters in the tonic key while the other voices weave counterpoint around it. If it is a four-voiced fugue, there is a fourth entry of the subject while the other voices continue in counterpoint. Here is a typical opening of a three-voiced fugue:

Â

Â

Collectively, a section with entries of the subject like this is called a

fugal

exposition

. Then follows a section where there is a kind of as-if improvisation on the exposition material, that section called an

episode

. The whole of the fugue proceeds in an alternation of exposition (entries of the subject) and episode (free counterpoint on the material). At the end there may be a section called the

stretto

in which, as if in its eagerness to be heard, the subject enters in the voices in closer succession, each entry almost treading on the heels of the last.

There are infinite variations. A fugue can be in two voices or up to as many as you like (but rarely more than six). There may or may not be a countersubject, or a stretto at the end. The piece may be a

double fugue

, involving two more or less equal subjects. There are smaller named variants based on the fugal idea: a

fughetta

is a little fugue, often an episode in a larger movement; a

fugato

is a fuguelike section involving a subject but is less developed than a full fugue.

Beethoven was fascinated by the fugal idea and turned to it often, especially in the late music. But he was determined to adapt fugue to the demands of Classical-style movements, and constantly found new ways of integrating fugue and sonata or sonata-like forms, or creating new formal patterns based around fugue. Since the model of a fugue composer for Beethoven was J. S. Bach (mainly in

The Well-Tempered Clavier

), the style of Beethoven's fugues sometimes recalls Bach.

Â

CANON

Â

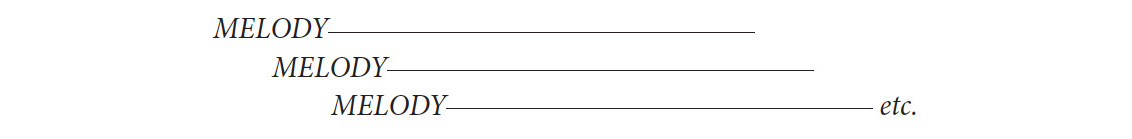

Canon resembles fugue in that it is a contrapuntal procedure based on a single subject, but it is a more rigid procedure than fugue. Think of canon as a grown-up form of “Row, Row, Row Your Boat”: the beginning of a melody is heard alone, then a second voice begins the same tune while the first voice continues it, and the idea continues with as many voices as you like:

Â

Â

So the single tune is heard two or more times in overlapping entries and creates counterpoint with itselfâin effective harmony. The canonic tune may or may not begin on the same pitches in each entry; there are other varieties, such as a

crab canon

, in which the second entry is the melody backward. Canons can't happen by accident; they have to be carefully composed. Bach was celebrated for the suppleness and beauty of his canons, qualities that are very hard to achieve in such a rigid form. Beethoven usually wrote freestanding canons only as jokes for friends, but some of his pieces have canonic episodes integrated into the larger form.

[Itzy]

Albrecht, Theodore.

Letters to Beethoven and Other Correspondence

. 3 vols. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1996. In the notes, called “Albrecht.”

Aldrich, Elizabeth. “Social Dancing in Schubert's World.” In Erickson,

Schubert's Vienna

.

Alsop, Susan Mary.

The Congress Dances

. New York: Harper & Row, 1984.

Anderson, Emily. “Beethoven's Operatic Plans.”

Proceedings of the Royal Musical Association, 88th Session (1961â1962)

.

âââ, ed. and trans.

The Letters of Beethoven

. 3 vols. London: Macmillan, 1961. In the notes, called “Anderson.”

âââ.

Mozart's Letters:

An Illustrated Selection

. Boston: Little, Brown, 1990.

Andraschke, Peter. “Neefe's Volkstümlichkeit.” In Loos,

Christian Gottlob

Neefe

.

Arnold, Denis, and Nigel Fortune, eds.

The Beethoven Reader

. New York: Norton, 1971.

Baker, Nancy Kovaleff, and Thomas Christensen, eds.

Aesthetics and the Art of Musical Composition in the German Enlightenment: Selected Writings of Johann Georg Sulzer and Heinrich Christoph Koch

. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995.

Beahrs, Virginia Oakley. “The Immortal Beloved Riddle Reconsidered.”

Musical Times

, February 1988.

âââ. “âMy Angel, My All, My Self': A Literal Translation of Beethoven's Letter to the Immortal Beloved.”

Beethoven Newsletter

5, no. 2 (Summer 1990).

Beethoven, Ludwig van. “Beethoven's

Tagebuch

.” Translated by Maynard Solomon. In Solomon,

Beethoven Essays

.

âââ.

Ein Skizzenbuch zu Streichquartetten aus op 18

. 2 vols., facsimile and transcription. Bonn: Beethovenhaus, 1972.

âââ.

Konversationshefte

. Edited by Karl-Heinz Köhler and Grita Herre. 11 vols. Leipzig: Deutscher Verlag für Musik, 1972.

Berlin, Isaiah.

The Age of Enlightenment: The Eighteenth Century Philosophers

. 1956. Reprint, Freeport, N.Y.: Books for Libraries Press, 1970.

Biba, Otto. “Concert Life in Beethoven's Vienna.” In Winter and Carr,

Beethoven, Performers, and Critics

, 77â93.

Blanning, Tim.

The Pursuit of Glory: Europe, 1648â1815

.

New York: Viking, 2007

.

Bodsch, Ingrid. “Das kulturelle Leben in Bonn under dem letzten Kölner Kurfürsten Maximilian Franz von Ãsterreich (1780/84â1794).” In Bodsch,

Joseph Haydn und Bonn

.

âââ,

ed

.

Joseph Haydn und Bonn: Katalog zur Ausstellung

. Bonn: StadtMuseum, 2001.

Bonds, Mark Evan.

Wordless Rhetoric: Musical Form and the Metaphor of the Oration

. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1991.

Bonner Geschichtsblätter

, herausgegeben von Stadtarchivar. Bonn: Der Verein, 1937â.

Bonner Intelligenzblätt

. There is a selection of issues of this late eighteenth-century town paper on microfilm at the Bonn Stadtarchiv.

Botstein, Leon. “Beethoven's Orchestral Music.” In Stanley,

Cambridge Companion

.

âââ. “The Patrons and Publics of the Quartets: Music, Culture, and Society in Beethoven's Vienna.” In Winter and Martin,

Beethoven Quartet Companion

.

Brandenburg, Sieghard. “Beethoven's Op. 12 Violin Sonatas: On the Path to His Personal Style.” In Lockwood and Kroll,

Beethoven Violin Sonatas

.

âââ. “Once Again: On the Question of the Repeat of the Scherzo and Trio in Beethoven's Fifth Symphony.” In

Beethoven Essays: Studies in Honor of Elliot Forbes

, edited by Lewis Lockwood and Phyllis Benjamin, 146â98.

Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1984

.

Brandt, G. W. “Banditry Unleash'd; or, How

The Robbers

Reached the Stage.”

New Theatre Quarterly

22, no. 1 (2006): 19â29.

Braubach, Max, ed.

Die Stammbücher Beethovens und der Babette Koch

,

in Faksimile

. Bonn: Beethovenhaus, 1995.

âââ. “Von den Menschen und dem Leben in Bonn zur Zeit des jungen Beethoven und der Babette Koch-Belderbusch.”

Bonner Geschichtsblätter

23 (1969): 51.

Breuning, Gerhard von.

Memories of Beethoven

. Edited by Maynard Solomon. Translated by Henry Mins and Maynard Solomon. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995.

Brinkmann, Reinhold. “In the Time of the

Eroica

.” In Burnham and Steinberg,

Beethoven and His World

.

Brion, Marcel.

Daily Life in the Vienna of Mozart and Schubert

. Translated by Jean Stewart. London: Weidenfeld & Nicholson, 1961.

Brophy, Brigid.

Mozart the Dramatist

. New York: Da Capo, 1988.

Brown, A. Peter.

The Symphonic Repertoire: The First Golden Age of the Viennese Symphony; Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, and Schubert

. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2002.

Brown, Clive. “Historical Performance, Metronome Marks, and Tempo in Beethoven's Symphonies.”

Early Music

19, no. 2 (May 1991).

Broyles, Michael.

Beethoven: The Emergence and Evolution of Beethoven's Heroic Style

. New York: Excelsior Music, 1987.

Burnham, Scott.

Beethoven Hero

. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1995.

Burnham, Scott, and Michael P. Steinberg, eds.

Beethoven and His World

. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000.

Cadenbach, Rainer. “Neefe als Literat.” In Loos,

Christian Gottlob

Neefe

.

Chua, Daniel K. L.

The “Galitzin” Quartets of Beethoven

. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1995.

Clive, H. P.

Beethoven and His World: A Biographical Dictionary

. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001.

Closson, Ernest. “Grandfather Beethoven.”

Musical Quarterly

19, no. 4 (October 1933): 367â73.

Comini, Alessandra.

The Changing Image of Beethoven: A Study in Mythmaking

. New York: Rizzoli, 1987.

âââ. “The Visual Beethoven: Whence, Why, and Whither the Scowl?” In Burnham and Steinberg,

Beethoven and His World

.

Cook, Nicholas.

Beethoven: Symphony No. 9

. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

âââ. “Beethoven's Unfinished Piano Concerto: A Case of Double Vision?”

Journal of the American Musicological Society

42, no. 2 (Summer 1989): 338â74.

Cooper, Barry.

Beethoven

. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000.

âââ.

Beethoven and the Creative Process

. Oxford: Clarendon, 1992.

âââ.

The Beethoven Compendium: A Guide to Beethoven's Life and Music

. New York: Thames & Hudson, 1992.

âââ.

Beethoven's Folksong Settings: Chronology, Sources, Style

. Oxford: Clarendon, 1994.

âââ. “The Compositional Act: Sketches and Autographs.” In Stanley,

Cambridge Companion

.