Beethoven: Anguish and Triumph (41 page)

Still, Beethoven had not yet settled on the kind of music he imagined writing, that reached beyond the confines of patrons' music rooms, that mattered the way Handel and J. S. Bach and Haydn and Mozart mattered. The dissatisfaction he expressed in the letter to Matthisson followed directly on the completion of the most sustained and ambitious project of his life, the six string quartets commissioned by Prince Lobkowitz. They had been Beethoven's major project for some two years; there is nothing comparable to their scope in the sketches of middle 1798 to late 1799.

18

Aware of the looming presence of the Haydn and Mozart quartets, painfully aware that Haydn had recently written some of his greatest ones, Beethoven composed the set with the most meticulous care. Having drafted them to the end, he returned to the F Major and G Major and possibly D Major and revised them with the advice of Viennese composer Emanuel Aloys Förster, a respected old hand with quartets.

19

(In the 1790s, Beethoven was a regular at Förster's twice-weekly quartet parties.)

20

Having given the manuscript of the first version of the F Major to Karl Amenda, Beethoven dispatched a letter to his distant friend, saying, “Be sure not to hand on to anybody your quartet, in which I have made some drastic alterations. For only now have I learned how to write quartets.”

21

All the op. 18 quartets turned out strong and listenable. As was second nature to him, each is knit together by patterns of keys, melodic and rhythmic motifs, gestural shapes. If they tend to be reminiscent of Haydn and Mozart, and well within the tradition of quartets written for amateurs, none of them are blandly conventional and all of them have probing ideas, even if sometimes the impact of the ideas does not rise to the level of the craftsmanship.

In other words, he composed the set cautiously, with Haydn and Mozart figuratively looking over his shoulder, knowing he was going to be submitting these pieces to Haydn's judgment in person. Haydn was, of course, no ordinary judge of string quartets. He had virtually invented the modern idea of the genre: a four-movement piece for instruments treated more or less equally (superseding the older, first-violin-dominated pieces). Under Haydn's nurturing, the string quartet had become the king of chamber-music genres, though still aimed toward skilled amateurs playing at home. As of 1800, there was no such thing as an established professional string quartet playing regular public concerts.

Haydn described his six quartets of op. 33, published in 1782, as written “in a new and special manner.” Besides a more near equality of the instruments, central to that new manner was systematic thematic workâusing a few small, recurring motifs to build themesâand a new wealth of expressive variety, integrating music in high style with folksy and comic material. Inspired mainly by op. 33, in the next years Mozart issued his splendid set of six quartets dedicated to Haydn. By then quartets were one of the most salable of genres, with enthusiasts everywhere and composers supplying those enthusiasts with hundreds of works. The quartet had become the chamber medium par excellence for connoisseurs and for fanatics, in a period when the favored amateur instruments were strings, not yet the piano. All over Europe, families and groups of friends played quartets together to entertain themselves and their circle. So quartets, like the other chamber genres, were private and social, in contrast to the more public and popularistic genres of symphony and opera.

Again mainly because of Haydn, there was a sense that quartets were the ultimate test not only of a composer's craft but of his heart and soul, his most refined and intimate voice. It was understood that in composing a quartet it was appropriate to be more subtle, idiosyncratic, and complex than in big public pieces. The strange, chromatic beginning of Mozart's C Major Quartet, the last of the Haydn-dedicated set, earned it the nickname “Dissonant.” A beginning that, harmonically gnarly, would have been out of place in a symphony, even for Beethoven.

As he began work, Beethoven knew that Haydn was working on his own set of six quartets also commissioned by Prince Lobkowitz.

22

As it turned out, Haydn was able to finish only two of the quartets and part of a third (the latter op. 103).

23

Age was unkind to Haydn. But as far as Beethoven knew, with his first quartets he would be competing with new Haydns written at the top of the old master's form. For the moment, then, Beethoven conceded the field. At the same time, he did his preparatory work, studying Haydn quartets and copying out the whole E-flat Quartet from op. 20.

24

Thus the contemporary rather than prophetic tone of the op. 18 Quartets. In later years, it would be written of them that Beethoven was “learning his craft,” “mastering form,” “finding his voice,” “looking backward.” None of that applies. The quartets show him as already a master craftsman, already with a mature understanding of form and proportion (though that understanding would greatly deepen and broaden), a composer who had already found much of his voice (though he had not fully settled into it).

25

Still, for all their relative modesty and eighteenth-century tone, the op. 18 quartets are ambitious in their way: well written for the instruments, widely contrasting in mood and color, at least as varied as any set by Haydn or Mozart, and full of ideas particular to Beethoven.

Â

After reading through the quartets with his group, violinist Ignaz ÂSchuppanzigh advised placing the F Major, the second composed, as no. 1 in the published set.

26

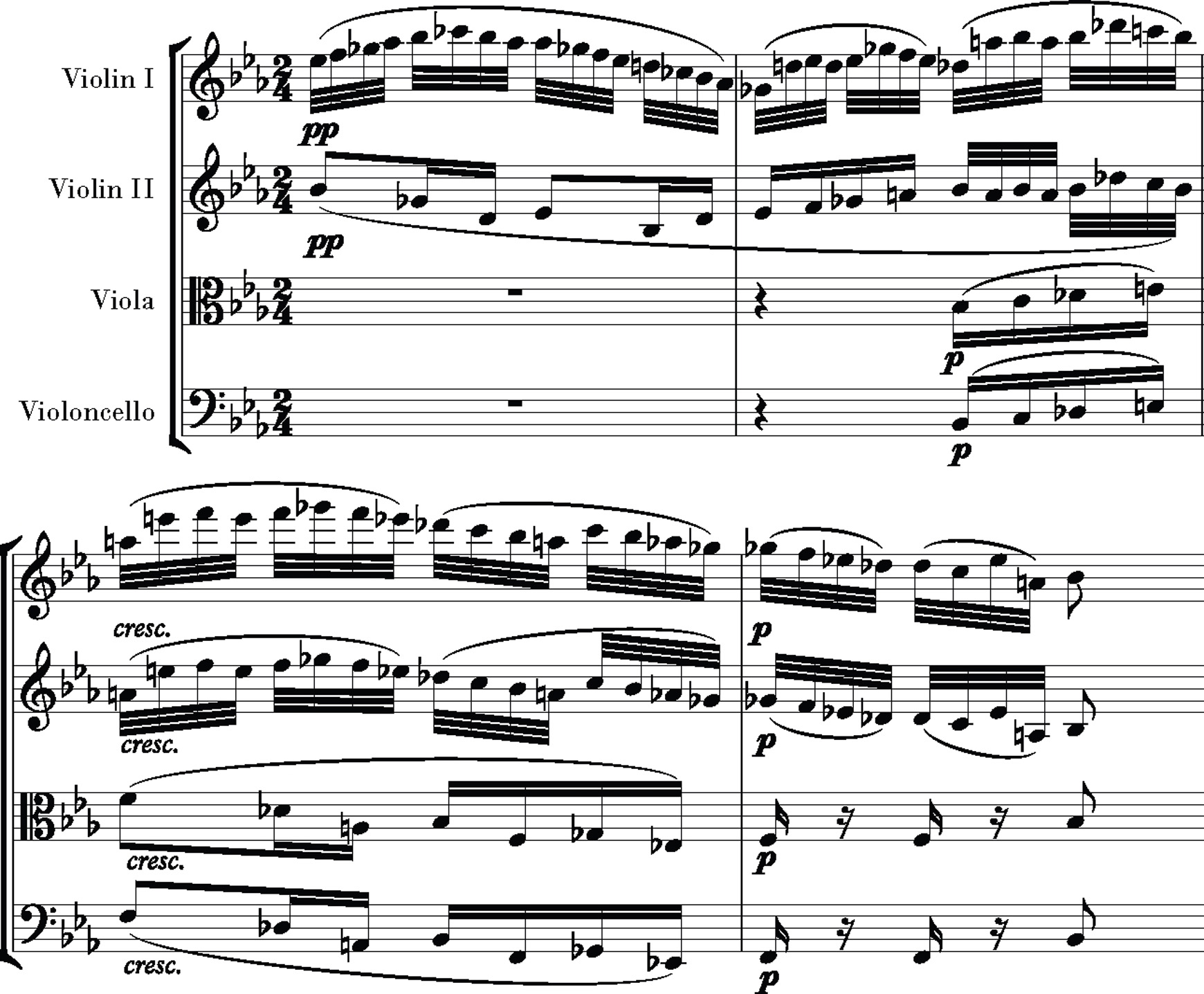

Beethoven agreed. The F Major has the most arresting opening, perhaps is the most consistent throughout the set. It starts with a sober movement driven by an obsessive repetition of a single figure whose significance is rhythmic as much as melodic.

In coming years Beethoven would return to similar monorhythmic movements, but later he tended to use repeated figures to sustain a sense of relentlessness, whether a mood of irresistible fate, or the spell of dance, or the blissful trance of a summer day. In the first measures of the F Major, the figure is presented blankly in quiet unison, then in a yearning phrase, then in a more aggressive

forte

. The obsessive theme is a blank slate on which changing feelings are projected. This being Beethoven, the opening idea also unveils the leading motif of the whole quartet, a turn figure. Between the published version of the F Major and the original version in Amenda's copy, with advice from old hand Emanuel Förster, Beethoven went back and made dozens of large and small changes in details compositional, textural, thematic: extending thematic connections, tightening proportions and tonal relations (he transposed long stretches of the development).

27

In the process he trimmed the appearances of the turn figure from 130 repetitions to 104.

28

The second movement of the F Major is one of the most compelling movements in op. 18. This is the music that Beethoven told Amenda was based on

Romeo and Juliet

. It is in D minor, the same as the Largo e mesto movement of op. 10, no. 3, so in a key in which Beethoven found a kind of singing, tragic quality. Here it is marked Adagio affettuoso ed appassionato: slow and warmly impassioned, the main theme a long-breathed, sorrowful song. In the middle of the movement a new figure intrudes, like the whirling of fate that swells relentlessly to a deathly end. There follow a brilliant and delightful scherzo and a briskly racing, perhaps a bit wispy finale that leaves listeners pleased, if perhaps puzzled as to how all this adds up.

The next quartet in the set, no. 2 in G Major, is jaunty and ironic from beginning to end, starting with the three distinct gestures of its opening, each like a smiling tip of the hat to the eighteenth century. Its slow movement starts elegantly

galant

, in 3/4, but that tone is punctured by an eruption of mocking 2/4 serving as trio. No. 3 in D Major was the first to be writtenâin other words, the first full string quartet of Beethoven's life. If the opening movement seems featureless to a degree, the finale manages to be an effervescent romp full of Haydnesque rhythmic quirks.

29

Its slow movement, in a dark-toned B-flat major, branches into deep-flat keys including E-flat minor. That movement shows off Beethoven's sensitivity to the contrast between keys involving open strings and keys that avoid open strings; to great effect, he juxtaposes dark and bright string keys throughout. No. 4 in C Minor is the only minor-key work in the opus, this one more aspiring to than attaining the dynamism of his C-minor mood.

30

The first movement has some apprentice echoes, awkward harmonic and phrasing jumps rare in his music.

31

Its gypsy rondo of a finale is the (relative) glory of this number. No. 5 in A Major has its quirky pleasures, including a dashing, as if opera buffa, finale.

No. 6 in B-flat Major was written last. Here more overtly and eloquently than in any of its neighbors in op. 18, Beethoven showed his hand in wanting to say something beyond music. To that end, he shaped a narrative both personal and universal. Its subject is the encroachment of depression.

When Beethoven was his student in Bonn, Christian Neefe had written that a composer must be a student not just of notes but of humanity. You need “a meticulous acquaintance with the various characters [of men] . . . with the passions . . . One observes the nuances of feelings, or the point where one passion changes into another.”

32

So Beethoven had been taught. In himself he had watched the nuances of feeling. Now he began putting that knowledge to use in ways that took him, in a work on the surface not notably “Beethovenian,” closer to his full maturity.

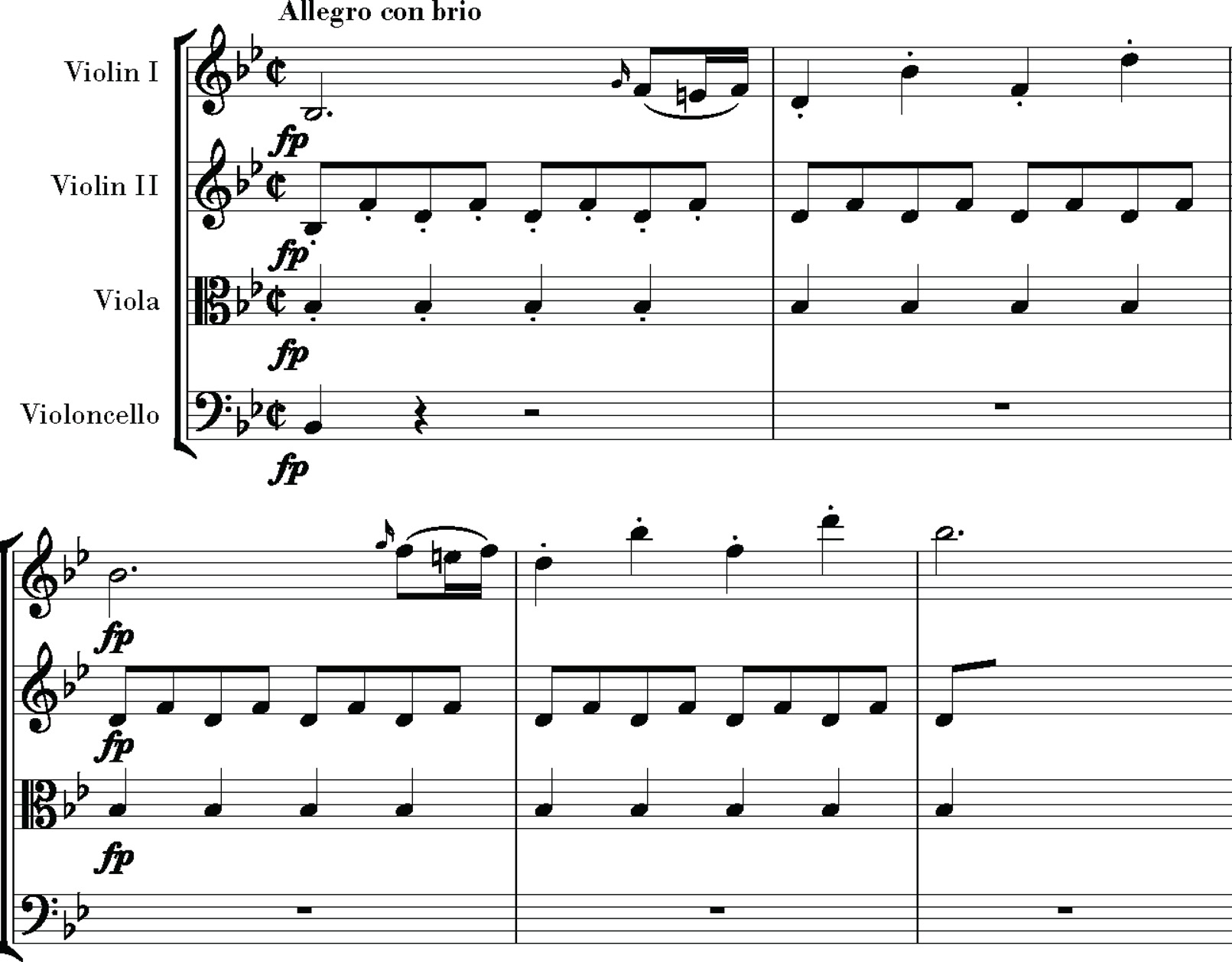

The quartet begins on a striding, muscular theme, buffa in tone, even a touch generic and foursquare. It is a Haydnesque theme, and Beethoven is going to play a Haydnesque game with it: set up the listener's expectations, then subvert them.

Â

Â

Whereas Haydn usually pursued that game with a wink for the connoisseurs who would get it, Beethoven plays it in fierce earnest. What the listener expects after the beginning of the B-flat Quartet is for the music to remain in uncomplicated, eighteenth-century high spirits. The second theme starts off in the expected second-theme key of F major, the tone elegant and refined, the rhythm with a touch of marching tread.

Then something intrudes, a shadow. The elegant march strays into unexpected keys, arriving with a bump on the chromatic chord called the Neapolitan, a harmonic effect that often has something unsettling about it.

Â

Â

After a few seconds, the shadow seems to pass, the music shakes itself back into F major, all is well again. Nothing really troubles the movement further until the recap, except that in the development the jolly tone gets sometimes a touch harsh, and in a couple of places the music trails off strangely into silence, like it has lost its train of thought. In the recap of the second theme, the harmony veers into B-flat minor and E-flat minor, then shakes off the shadow again.

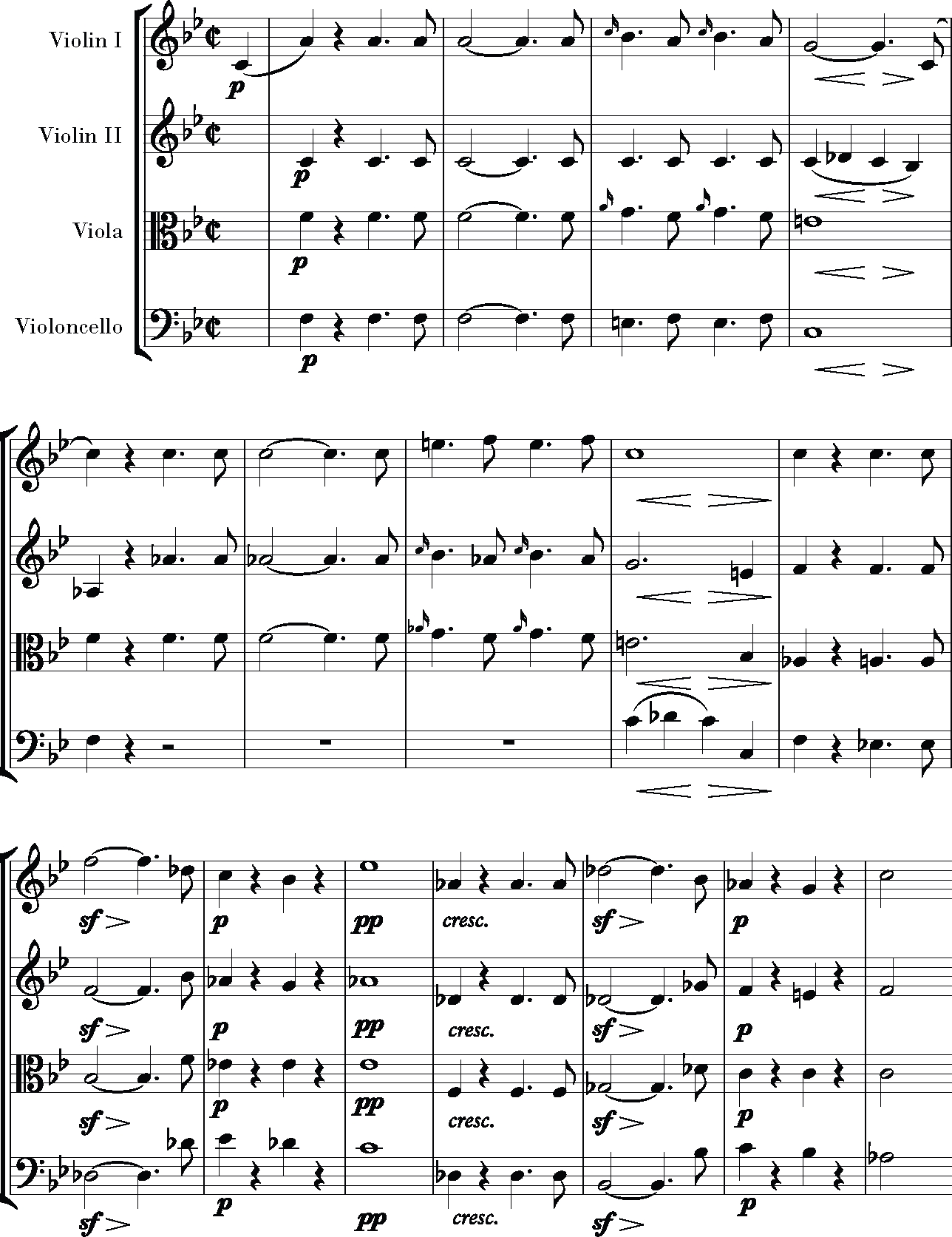

The second movement begins in a blithe and galant mode, but that is a mood made to be spoiled. In the middle part, the music slips again into E-flat minor, one of Beethoven's most fraught keys, usually implying inward sorrow. Here it is, an eerie, spidery, keening whisper, all of it based on a twisting motif:

Â