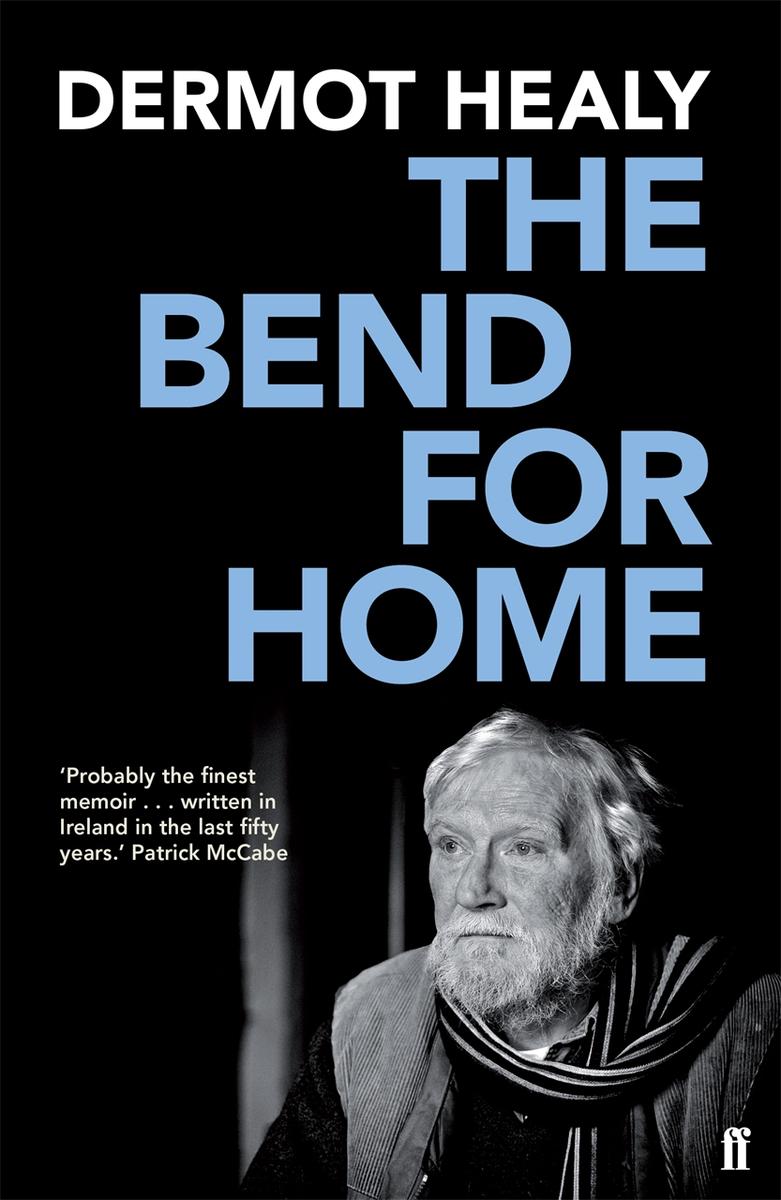

Bend for Home, The

Read Bend for Home, The Online

Authors: Dermot Healy

Further praise for

The

Bend

for

Home

:

‘This is a marvellous book, satisfying on just about every one of its many diverting and artful levels.’ George O’Brien,

Irish

Times

‘It would be hard to exaggerate the excellence of Healy’s writing. Understatement is part of it: the story is bursting with passion, but it is contained in looks and slight remarks, which become loaded with meaning.’ James Robertson,

Scotland

on

Sunday

‘A wonderfully strong, witty and clever memoir.’ Margaret Forster,

Literary

Review

‘Healy’s novel

A

Goat’s

Song

is one of the great Irish novels of the nineties. This new narrative, mingling autobiography with deceptive imaginative flights, is just as powerful.’ Neil Sowerby,

Man

chester

Evening

News

‘The narrative soars. It is vivid, lively and often moving.’ Eileen Battersby

‘An impressive act of recreation.’ Patricia Craig,

Times

Literary

Supplement

‘His marvellously evocative, rich affect-laden prose illuminates a childhood and an adolescence with tender frankness.’ Anthony Clare,

Sunday

Times

Dermot Healy

A

Memoir

Corr baile

(

Irish

). The bend for home,

which gives rise to many place names in Ireland,

as for example Corballa, Corbellagh, etc.

Just

turn

to

the

left

at

the

bridge

of Finea

And

stop

when

halfway

to

Cootehill

PERCY FRENCH

The author would like to thank Robin Robertson, the editor of

32

Counties

by the photographer Donovan Wylie (Seeker & Warburg, 1990) in which part of “The Bridge of Finea” appeared in an earlier form, and Brian Leyden, the editor of

Force 10

magazine (Spring 1996) and Johnny O’Hanlon, the editor of the 150th anniversary supplement of the

Anglo-Celt

(June 1996), in which extracts from “The Sweets of Breifne” appeared.

- Title Page

- Note on the text

- Epigraph

- Acknowledgements

- BOOK I

The

Bridge

of Finea - Chapter

1 - Chapter

2 - Chapter 3

- Chapter

4 - Chapter 5

- Chapter

6 - Chapter

7

- BOOK II

The

Sweets

of Breifne - Chapter

8 - Chapter

9 - Chapter

10 - Chapter

11 - Chapter

12 - Chapter

13 - Chapter

14

- BOOK III

Out

the

Lines - Chapter

15 - Chapter

16 - Chapter

17 - Chapter 18

- Chapter

19 - Chapter

20 - Chapter

21

- BOOK IV

Sodality

of

Our

Lady - Chapter

22 - Chapter

23 - Chapter 24

- Chapter 25

- Chapter 26

- Chapter 27

- Chapter 28

- BOOK V

It’s Lilac Time Again - Chapter 29

- Chapter 30

- Chapter 31

- Chapter 32

- Chapter 33

- Chapter 34

- Chapter 35

- About the Author

- By the Same Author

- Copyright

The doctor strolls into the bedroom and taps my mother’s stomach.

You’re not ready yet, ma’am, he says to her.

Be the holy, she trustingly replies.

That woman of yours will be some hours yet, he tells my father on the porch. He studies the low Finea sky. You’ll find me in Fitz’s.

The doctor throws his brown satchel into the back of the Ford that’s parked at an angle to our gate and ambles up to the pub. My father sits on a chair at the bottom of the bed. My mother has a slight crossing of the eye, and because she hasn’t her glasses on she looks the more vulnerable. He has had water boiling downstairs all day. He’s wearing the trousers of the Garda uniform and smoking John Players. The November night goes on. Some time later she goes into labour again. My father runs up the village and gets the doctor from the pub.

He feels her stomach, counts the intervals between the heaves, then says, Move over.

My mother does. He unlaces his shoes and gets in beside her.

Call me, ma’am, when you’re ready, he says and falls into a drunken sleep.

My father is waiting impatiently outside on the stairs. Time passes. The snores carry to him. Eventually he turns the handle and peers into the low-ceilinged room. He can’t believe his eyes.

Jack, she whispers, get Mary Sheridan, do.

He brings Mary Sheridan back on the bar of his bike. The tillylamps flare. At three in the morning the midwife delivers the child. Where the doctor was during these proceedings I don’t know. As for the child, it did not grow up to be me, although till recently I believed this was how I was born. Family stories were told so often that I always thought I was there. In fact, all this took place in a neighbour’s house up the road, and it was my mother, not Mary Sheridan, arrived on her bike to lend a hand.

It’s in a neighbour’s house fiction begins.

*

We have a surprise for you at home, my father told my brother on the train from Multyfarnham College.

Tell me what it is?

Wait and see.

Go on, Daddy.

It wouldn’t be a surprise if I did.

Just give me a clue.

My father shook his head.

Can you get up on it? Tony asked.

My father laughed.

Has it wheels?

Whisht! said my father. Just wait and see.

It was a long train journey for Tony. In his mind’s eye he saw a black Raleigh bike parked under the stairs. On the walk from the station he pestered my father with questions, but all to no avail. They arrived to the house. My mother welcomed him at the door. He was sent ahead into the kitchen.

He approached the pram.

In disbelief and disappointment, he looked in and saw me.

*

Finea sits on the river Inny which runs between Lough Sheelin and Lough Kinale under a mighty bridge that divides Cavan from Westmeath. Sheelin, troubled over recent years by pollution from pig farms, was then a powerful, whitewashed, lustrous lake. But Kinale is always magical and dark.

The seven arches under the bridge are caves where rain is always seeping. Human and animal turds steam there. Tom Keogh drives cattle down the path to drink from the river. Eels slither by. A family keeps eel-boxes upriver and you can peer through the holes to see them, all moist and black and uncoiling. The fish-stench is overpowering. The eels are more dangerous than a can of worms. Their camouflage is weed and shadow. A sudden dart across the sandy bottom. A loop-flick as they kick up a cloud of gravel. Then darkness. Sonny Coyle cuts the heads off the eels on the step of his shop. Cats carry them off down the village with angry growls.

Trout skate mid river in the shallows, watch our worms approach,

then skip out of the way. They are aristocrats. All facing the same way, they feint from side to side in a pool of fast sunshine. They have two seasons – before the mayfly and after the mayfly. Meanwhile, we bake perch in a stone fire under the bushes in Fitzsimon’s field, and eat them, bones and all.

Oil-skinned fishermen from abroad, with long dappling rods, steady each other as they climb collapsing walls. Flies hang from the brims of their caps like tassels. They carry sandwiches and bait. They push off in a boat. One flick of an oar and they’re gone.

We swim in the river, boys and girls, tall cold water to our necks. Girls were never so white as then. Neither were we. You dive under someone’s legs and frighten a shoal of minnow. Stout perch eye you. One day the cows ate the girls’ clothes and they had to go up the village in their knickers.

On the east side of Kinale the water is covered with unexplained layers of dry sifting yellow reeds. On the west, whispering acres of them grow, taut and green.

*

There was a cousin of mine who lived in Kildare. He was by the same first name as myself. Originally he’d been called Fergus, but for fear he’d be called Fergie they changed his name to Dermot after me. I was six months his senior. His father, Uncle Jim, same as Uncle Seamus, drove a sweet van.

From he could talk Dermot in Celbridge heard of the doings of Dermot in Finea. Seemingly I could wash dishes, carry turf, knew my alphabet, had no bother going to school, did everything I was told and had mastered Irish. If he cried they told him Dermot Healy did not cry. Not only that but Dermot Healy said his prayers morning noon and night. If he didn’t eat his dinner he heard how I could finish all before me. When he couldn’t sleep they told him that I slept round the clock.

By the time he was three Dermot had come to despise the sound of his own name because it called to mind his alter ego in Finea. He was tormented. It was Dermot Healy this and Dermot Healy that till he was sick of me. Time came, one summer, when Nancy and Jim Kinane and Dermot set off in the sweet van from Kildare to visit us in the County Westmeath.

I was told the night before that my cousin was coming so I was up at dawn standing by the pier of the gate looking towards Castlepollard for a sign of the blue van. They called me in for breakfast and then I was out again. Dinner, the same. I sat on the wall and counted the hours. When anyone passed I asked them the time.

When the blue van appeared at the pump in the late afternoon I was distraught from waiting.

They pulled in some distance away. My father appeared and Jim took his hand. Nancy stepped down to greet her sister. I stood watching. Dermot slipped off the running-board onto the road and stared straight at me.

Who do you think that is? said Uncle Jim.

I looked at the ground and put my hands in the pockets of my short trousers.

Who do you think, well?

Dermot came forward. He stopped and appraised me from a few feet away.

Well, say something, said Uncle Jim.

Say hallo to your cousin, Dermot! hollered Aunt Nancy.

The adults turned to watch the two of us with benign interest.

Shake hands, said Uncle Jim.

I was toeing gravel and looking sideways. Dermot stepped up to me and hit me with all the strength of his fist across the face. I went on my arse astonished. With Nancy at his heels my cousin took off up the Green Hill.

*

In 1912 my mother was seven. She walked into the lower spirit-grocers to get mints. Behind the shop counter was the woman of the house. Behind the bar counter was the man, without a stitch on him. He had a black umbrella over his head.

Why? I asked my mother.

To get his own back on his wife, she told me, pressing her hands into her lap, then seconds later slapping her knees. The cursed drink, she added, shaking her head at what memory will do.

*

It’s a thunderstorm. Uncle Tom from England, who bets on horses, and his wife Bridgie, my mother’s sister, are in the small rowing boat.

My father is at the oars. We’ve been fishing Kinale pike.

A pike turns on its belly beyond the reeds.

Uncle Tom cries: Bloody hell! Did you see that, Jack?

Another pike, in an angry splash, devours some fry.

The blighter, he says.

The unseen sun sends out a column of light from behind a dark cloud. Bad weather races towards us. Then the storm breaks.

The boat, with a rattle of boards, goes dangerously high. Vexed waves splash in. Rain pelts down. There is nothing underneath us. And in the uproar my father loses an oar.

The curse of the crows on it, he says, and, shamefaced, he grimly tries paddling after it.

What next? says Bridgie.

A dark mist falls. We see nothing. Around us, the bated water goes calm. Then it grows clear as day. My father’s face lights up like a stranger’s. The rumble seems to start under water. Then the awesome crack. Aunty Bridgie is wearing a green sou’wester and Wellingtons. Uncle Tom is wearing a straw hat. I sit between my father’s legs, which are braced firmly against the struts. We go round in circles. Bridgie starts oaring with Tom’s hat.

Blessed God, says my father.

The lightning strikes above Finea. It cracks across the surface of the lake. Then the sun shines. The water grows vexed again.

We are out there for hours. Then the keel softly parts the reeds near Brian McHugh’s. We grab the reeds gratefully. Hauling reeds Tom whistles a cockney air. My father stands at the prow pushing us forward with the remaining oar. Darkness falls. The air pulsates. Frightened ducks take flight. We are in the reeds for a long time. I will never forget their sound. And the sky cracking over. At last we touch land.

All in the boat, except me, are dead.