Bette and Joan The Divine Feud (41 page)

The Oscars

In January 1963, during the preliminary canvassing for Oscar nominations, Warner Brothers pushed Bette and Joan as Best Actress for

Baby Jane.

In February when the nominations were released, only Bette made the list (along with Anne Bancroft for

The Miracle Worker,

Geraldine Page for

Sweet Bird of Youth,

and Lee Remick for

Days of Wine and Roses).

When asked to comment on her loss, Crawford said, "But I always knew Bette would be chosen, and I hope and pray that she wins."

"That's so much

bull!"

said Bette. "When Miss Crawford wasn't nominated, she immediately got herself booked on the Oscar show to present the Best Director award. Then she flew to New York and deliberately campaigned

against

me. She told people

not

to vote for me. She also called up the other nominees and told them she would accept their statue if they couldn't show up at the ceremonies."

Dorothy Kilgallen reported that Anne Bancroft, acting in

Mother Courage

on Broadway, had requested Patty Duke accept for her. "But Patty is also up for an award and will not be allowed to accept for Bancroft. So Joan Crawford will do the honors if she wins," said Kilgallen.

"I received a lovely note of congratulations from Miss Crawford," said nominee Geraldine Page. "And then she called me. I was tongue-tied, very intimidated in talking with her. To me she was the epitome of a movie star. I always loved her movies. In fact, the character I played in

Sweet Bird of Youth

was said to be based partly on Joan Crawford. That's what I heard. In the movie I also used certain things I admired about her, and about Bette Davis. When I walked down the stairs in the filming of the movie scene—I had seen Bette do that in one of her movies. And later, when I'm in the theater watching that scene, I lowered my glasses and looked over the rims at the image of myself on the screen. I had seen Joan Crawford do that in a photograph from one of those old movie magazines. Growing up, I was a big fan of Bette Davis and Joan Crawford. As a teenager, I had seen almost all of their movies. But when Miss Crawford called, I told her nothing of that. I was tongue-tied. All I could manage was, 'Yes, Miss Crawford. No, Miss Crawford.' When she mentioned about accepting the Oscar for me if I won, I said yes. Actually I was relieved. That meant I wouldn't have to fly all the way to California, or spend a lot of time looking for a new dress to wear. I was happy and honored that Joan Crawford would be doing all of that for me."

On the evening of April 8, the thirty-fifth annual Oscar ceremonies were held at the Civic Auditorium in Santa Monica. That entire day, Crawford prepared for her dazzling appearance. Her silver-beaded gown had been designed by Edith Head. Her diamonds, for her wrists, ears, and neck, were on loan from Van Cleef and Arpels. Her hair, which had been washed and set and curled by Peggy Shannon, was dusted with a fine silver powder to match the rest of her combative glitter.

In her new Colonial-style house on Stone Canyon in Bel Air, Bette Davis was also giving special attention to her appearance for the Oscar show. Her dress was likewise by Edith Head. Her face had been rejuvenated by minilift expert Gene Hibbs, and the evidence, the adhesive tapes and clips, was covered over by a fetching auburn wig with bangs. Before leaving the house, Bette "had a long talk with my two tarnished Oscars on the mantelpiece. And I promised to bring them home a baby brother."

That she would win was a foregone conclusion to Bette. "I was positive I would get it, and so was everybody in town."

Escorted by Cesar Romero, Joan Crawford was the first arrival at the Civic Auditorium and "made a beeline for the fans, getting down on her knees to sign autographs for some of the blocked-off people."

When asked by a TV reporter whom she had voted for in the Best Actress category, Joan deftly answered, "The winner!"

Bette arrived with daughter B.D., son Michael, and Olivia de Havilland, who told reporter Army Archerd that she had flown in from Paris for this important occasion. "Bette deserves to win. She's the greatest and the industry owes her this," said Olivia.

"Yes, I want that Oscar," Davis told Archerd. "I

have

to be the first to win three."

Backstage, Crawford once again held court. In the main dressing room, she had a wet bar set up, with Pepsi coolers filled with bourbon, scotch, vodka, gin, champagne—"plus four kinds of cheese and all the fixings." She also had a large TV monitor installed, so her guests could watch the show as it unfolded onstage. "Look at that Eddie Fisher, giving newcomer Ann-Margret all the camera angles," said Joan. "He sure has a way with the ladies."

Down the hall, in Frank Sinatra's dressing room, Bette sat holding hands with Olivia de Havilland.

As the final top five awards came up, Crawford, Bette, and Olivia moved from backstage to the wings. Joan looked radiant, and to show her admiration, Bette Davis went up behind her to kiss her on the back of the neck. "Thank you, dear," Joan whispered. "It was the nicest thing a human being could do," Crawford told reporter Len Baxter, "so dear of her, so gentle, and I was deeply touched. I really thought we were friends." ("That

nevah

happened," said Davis when she was told of the report.)

To the strains of "Some Enchanted Evening," Joan swept onstage to present the Best Director award, to David Lean for

Lawrence of Arabia.

As Lean and Joan exited arm in arm, Bette Davis came onstage, to present the award for Best Original Screenplay. In an aside to the audience, she said that the writers she had known during her long career "were among the surliest in Hollywood." After stumbling over the pronunciation of the foreign names, she ripped the envelope open and said the winners were "Those three difficult Italian names, for

Divorce Italian Style."

Joan "steals" Bette's Oscar

Then the big moment arrived—the category of Best Actress. Contender Bette and surrogate receiver Joan stood in the wings, three feet apart, chain-smoking. As Maximilian Schell stood onstage, reading the names of the five nominees, Bette handed her purse to Olivia de Havilland. Opening the envelope, Schell paused, then announced: "The winner . . . Anne Bancroft for

The

Miracle Worker."

"I almost dropped

dead

when I heard Miss Bancroft's name," said Bette. "I was

paralyzed

with shock."

"Joan stood instantly erect," said TV director Richard Dunlap. "Shoulders back, neck straight, head up. She stomped out her cigarette butt, grabbed the hand of the stage manager, who blurted afterwards, 'she nearly broke all my fingers with her strength.' Then with barely an 'excuse me' to Bette Davis, she marched past her and soared calmly on stage with the incomparable Crawford manner.

"Bette bit into her cigarette and seemed to stop breathing," said Dunlap. "She had lost the award. Joan was out

there—suddenly

it was

her

night."

"I

should have won," said Bette. "There wasn't a doubt in the world that I wouldn't. And Joan—to deliberately upstage me like that—her behavior was despicable."

"Disloyalty never entered my mind," said Crawford. "If Geraldine Page had won, I'd have been glad for her. I'm working for an industry, not an individual."

"The triumph of the evening," said

Time,

describing Joan Crawford as she posed backstage with the winners.

"She kissed Gregory Peck, she kissed Patty Duke, she kissed Ed Begley. She would have kissed the doorman and the limo drivers too, if it meant she could get another photograph taken," said Sidney Skolsky.

In her column the next day, Hedda Hopper summed up the event. "I was rooting for Bette. But when it comes to giving or stealing a show, nobody can top Joan Crawford."

19

Bette Bounces Joan from Cannes

I

n February 1963, to launch the film in Europe, Elliott Hyman, president of Seven Arts, instructed Bob Aldrich to invite Bette Davis and Joan Crawford to attend the showing of

Whatever Happened to Baby Jane?

at the Cannes Film Festival, then fly to London for the British premiere.

In the aftermath of the Oscars, one invitation was rescinded.

"Basically Mother didn't want to go to Cannes," said B.D. Hyman. "She preferred to stay home. I was the one who bulldozed her into going. I was sixteen, I wanted to see Cannes. Mother gave in and issued an ultimatum to Bob Aldrich. She said, 'I'll go, but

not

with Joan Crawford. I won't share it with her.'"

Bette Davis was a bigger draw in Europe, and it was up to Aldrich to tell Joan that she was disinvited.

Crawford, in 1973, said it had been

her

decision not to go. "Those festivals are a zoo, a real zoo," she said. "And I didn't care to subject myself to any more unpleasantness from Miss Davis."

The producer's files at the American Film Institute told another story. When her invitation was rescinded, Crawford threatened to bring legal action against Bob Aldrich and Bette Davis, who she felt were maligning her reputation.

"Mother was telling these silly stories about how Joan took the Oscar to bed with her on the night of the awards," said B.D.

"She wouldn't give the damn thing up," said Bette. "She packed it in her luggage the next day and carried the award with her on a trip around the world for Pepsi-Cola. It was six months before she even let Anne Bancroft

see

her Oscar."

On May 5, 1963, Crawford's lawyers in New York, Seligson and Morris, dispatched a telegram to Bob Aldrich Associates. It read in part: "On behalf of our client, Joan Crawford, we hereby advise you that you will be held liable and accountable for all loss, damage, and injury sustained by her in connection with your actions relating to her attendance at the Cannes Film Festival and further that you and Miss Davis will be held strictly accountable for any false or misleading statements or publicity concerning the circumstances under which you have cancelled arrangements for Miss Crawford to attend the aforesaid Festival."

On May 6 Aldrich's law firm, Prinzmetal of Beverly Hills, responded. They advised Crawford's lawyers that their client could not "be responsible for any false or misleading statements or publicity which may be issued by Miss Davis, have no reason to believe that such statements were or will be made by Miss Davis, or by Mister Aldrich."

A copy of the wire was sent to Davis' lawyer, Tom Hammond, who was told, in short, to advise Bette to put a lid on it when it came to the topic of Joan Crawford.

Arriving in Cannes with Aldrich, Davis told the packed press conference at the Carlton Hotel that she had no idea why her costar wasn't along for the trip. "Certainly she was

invited,"

said Bette, "but Joan is a busy,

busy

woman. And I know we will all miss her

terribly!"

The Feud Rolls On

When the profits from

Baby Jane

were tallied that July, another dispute arose. The gross on the income statement from Warner's—Seven Arts was $3.5 million, and not the ten or twelve million dollars that was widely mentioned. After the negative and distribution costs were deducted, Crawford received approximately $150,000 and Bette seventy-five thousand, minus thirty thousand for repayment of a loan Aldrich Associates had advanced to her as a down payment for the purchase of Honeysuckle Hill, her new Colonial-style home in Bel Air.

Dissatisfied with her share from

Baby Jane,

Bette requested that her lawyer be allowed to examine the books at Warner's, but the figures were confirmed by Bob Aldrich and, close to broke again, Bette had to solicit work. The previous September, when

Baby Jane

wrapped and no other scripts were forthcoming, she had placed a "situation-wanted" advertisement in the employment section of

Va

riety.

All of Hollywood, and Joan Crawford, expressed amazement that the great Davis would openly ask for work. "I would pack my bags, get on a bus, and work as a waitress in Tucson before I would belittle my name by begging for a job," said Joan.

"Every time the goddamn widow Steele holds up a bottle of Pepsi-Cola they give her a thousand bucks," said Bette, lashing back. "I am

not

Joan Crawford. I am

Bette Davis,

a working mother."

The ad was a joke, Davis later claimed, as were some of the offers it produced. She was offered the role of Dick Van Dyke's mother in the Vegas production of

Bye Bye, Birdie.

She declined, but agreed to guest-star on TV's

Perry Mason

and to sing and dance on the Andy Williams variety show. Bob Aldrich then hired Bette to play the supporting role of a madam in

Four for Texas,

a western starring Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin, and the Three Stooges. She was being fitted for her brothel costumes when Jack Warner called with a better deal. He had a project,

Dead Ringer,

set to go with Lana Turner playing dual roles. But Lana, it was said, didn't want to play twins, figuring, and rightly so, that one edition of her gorgeous self was enough for the general public. When she turned down the film, Warner presented it to Davis, who got a release from Aldrich. She played twins before, she said, but the special effects were more complex and frustrating this time. A visitor to the set agreed. ''It was hardly the apex of comfort for an artist like Bette Davis to play a scene where, as twins, she must put a gun to her head and blow her own brains out."

Crawford had toiled earlier that year, in

The Caretakers,

playing Lucretia Terry, the tough head nurse in a psychiatric institution. With steel-dusted hair and individual key-spot lighting, Joan taught judo to the younger nurses and got her own mad scene, though it was cut from the final picture. "I was changed from a cameo part to just an angry woman," said Joan. "The director's excuse was that some of my scenes made me look cheap. But every woman who's rejected by the man she loves looks cheap. I should know, I'm a woman."

After washing the silver out of her hair ("I found I was throwing away all my beige clothes—because they were designed for a redhead. And, mentally, gray hair dampened my spirits"), Crawford, as a russet brunette, descended further into the pit of the not-so Grand Guignol, with her next alliance, with producer-director William Castle.

An independent producer-director specializing in horror and terror films, William Castle had none of the style or talent of Robert Aldrich. Fond of showing up at his own premieres in a coffin and hearse, and suspending twelve-foot skeletons on wires over the heads of the audiences, Castle scored his first box-office success in 1959, with

The Tingler.

His trademark was a decapitated head that appeared in many of his films. "We used the same old dead head in every movie," said the producer proudly. "We bought it for $12.50. That was the head that was used in

Psycho.

They rented it from us for a hundred a day."

After seeing

Whatever Happened to Baby Jane?

fifteen times, Castle dreamed of hitting the big time, of working with stars like Bette Davis and Joan Crawford. One evening, at a party in Beverly Hills, he had the good fortune to be introduced to Crawford. "He almost fell at her feet," said writer Hector Arce. "He told her he had a script that was commissioned specifically for her. It was called

Straitjacket.

It was written by the man who wrote the Hitchcock classic

Psycho."

"I'm listening, Mr. Castle," said Joan.

Castle told her the story. It was a psychological murder mystery, about a deranged woman who finds her husband in bed with his mistress and chops their heads off. She spends twenty years in a mental institution, is cured, and is then released to the care of her loving daughter. She is happy and readjusted to society, when a fresh series of beheadings occur in the town.

"Ummm," said Joan.

"She is the suspected killer," said Castle. "She believes it herself."

"And?" said Joan.

"She is arrested. But she's not the killer; it's her twisted daughter."

"The little bitch," said Joan. "When can I see the script?"

After Crawford read

Straitjacket,

she called the director. The woman was supposed to age from thirty to fifty. Joan wanted to make the character younger, to lop off five years at each end. Castle agreed. He also said yes to her salary, percentage, and contract demands.

When she was announced for the picture, she was immediately blasted by Bette Davis and Louella Parsons.

"Straitjacket

was supposed to star Joan

Blondell,"

said Bette, "until Crawford stepped in and

stole

the role."

"Joan Blondell was set for the lead and had been fitted for her costumes," Parsons confirmed. "Then out of the blue, producer William Castle signs the other Joan. And then he proceeds to turn his picture upside down to please her. Even the crew has been revamped, with a new cameraman, makeup man, hairdresser, costumer—even a switch in the publicity man. No one involved is talking."

"It stinks, I tell you," said Bette. "There is an unwritten

law

in this town. Once an actor is signed for a part, it's

his

until they die or drop out voluntarily. Miss Crawford

knows

this and should be ashamed of herself."

*4

The following February photographs of Bette and Joan appeared side by side in

Time

with reviews of

Dead Ringer

and

Straitjacket.

Both films were panned. "A trite little thriller. Exuberantly uncorseted, her torso looks like a gunnysack full of galoshes," said

Time

of Bette and

Dead Ringer;

while her rival received a flip New York

Times

notice: "Joan Crawford with an axe. Tennis, anyone?"

Of the two competing films,

Straitjacket

took in more money, helped somewhat by Joan's charismatic in-person tour of theaters. Using the Pepsi jet, the star flew cross-country to give the press and her public one "last look at the old tradition of Hollywood hoopla."

Her entourage included her maid, Mamacita; public-relations man Bob Kelley; a girl photographer; and two Pepsi pilots, who flew the plane from city to city; plus twenty-eight pieces of luggage, including food hampers, two knitting bags, and an axe with a three-foot haft, which Joan would carry onstage from theater to theater.

"She criticized

me,

for raffling off dolls onstage for

Baby Jane,"

said Bette Davis, "and she's got a goddamn axe under her skirt?"

Star Wars Part Two

"The second time around, Bette

wanted vengeance. It was

Elizabeth the First, all over

again. A mere apology from Joan

wasn't enough. Bette wanted her

head."

—GEORGE CUKOR

"I have always believed in the

Christian ethic, to forgive and

forget. I looked forward to

working with Bette again. I had

no idea of the extent of her hate,

and that she planned to

destroy me."

—JOAN CRAWFORD

In the winter of 1963, when Bob Aldrich's follow-up film

Four for

Texas

failed to attract a wide audience, he turned his thoughts to the idea of reteaming Bette and Joan. He asked

Baby Jane

novelist Henry Farrell to write a new story featuring the two stars. Farrell came up with a tale of malice and murder set in the Deep South. Bette would play an aging eccentric Southern belle, whose wealth and sanity are threatened by a visiting cousin. Also figuring prominently would be a domineering father, an unsolved murder, a buried body, and the razing of the family mansion. The working title of the story was

Whatever Happened to Cousin Charlotte?

Bette read the first draft of the script and agreed to play Charlotte. Meeting with Aldrich, she asked whom he had in mind to play Cousin Miriam. He said Ann Sheridan was a possibility.

"Good choice," said Bette.

"But most of the studios have requested Joan Crawford," the director stated.

"I wouldn't piss on Joan Crawford if she were on fire," Bette replied.

Aldrich then talked

money

with Bette. With Crawford as part of the package, the budget would be larger and Bette would get $120,000 upfront, which was double the sum she got for

Baby Jane;

and he would give her a percentage of the profits. "Forget the percentage," said Bette. "I got screwed on

Jane."

Aldrich raised his offer to $160,000, pushing Joan and advocating the script. It was Oscar material, he felt, "a much more difficult, narrow-edged part, with the Gothic bravura of Jane." As Cousin Charlotte, Bette would rule the plantation, dominate the story,

and

at the finish have the pleasure of crushing Cousin Miriam (Joan) to death with a massive concrete flowerpot.

"I

will

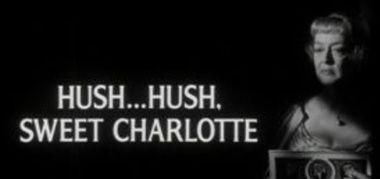

accept Crawford if you will change the title of the picture to

Hush .

..

Hush, Sweet Charlotte,"

Bette replied, referring to the name of the title song, composed by Frank DeVol and Mack David.

With Davis amenable to working with her rival again, Aldrich had to persuade Crawford to come aboard. He had not met or spoken with her since the unpleasantness over the rescinded Cannes Festival invitation. "Taking no chances on writing or phoning, the director sent the script to Joan in New York, then showed up on her doorstep," said reporter Len Baxter.

"You got a problem, Bob?" said Joan, when an awkward lull came up in their conversation.

"Yes," said Aldrich, "I was wondering ... would you ... could you ..."

"You wasted time and money, coming to see me," said Joan. "The answer is yes."

She liked the character of Miriam—a bitch, but a stylish one. Unlike Blanche in

Baby Jane,

in the new film she would be ambulatory, and in one scene she would get to slap Bette repeatedly across the face then push her down a ravine locked in the arms of a dead Joseph Cotten.

She told the director she would also accept the fifty thousand dollars in salary, with 25 percent of the net profits, plus five thousand in living expenses for the duration of the nine-week shoot.

"There is just one request I have to make," Joan concluded firmly.

"Name it," said Aldrich.

"In the billing for

this

picture my name comes first,

before

Miss Davis."

"In a

pig's

eye," Bette shouted when Aldrich called her from New York with Joan's request. "I will

not

have my name come

second

to Joan Crawford, not now, not ever."

Back in Los Angeles, further sweetening was offered to Bette by Aldrich. To get her to agree to take second billing to Joan, the director had to raise her salary another forty thousand dollars, to two hundred thousand. "That is the same amount I am getting for producing and directing," he told her, "so that makes us partners on this picture."

"Partners,

all the way down the line. I will hold you to

that,"

said Bette.

On December 28, 1963, the announcement appeared in the New York

Times

that the stars of

Baby Jane

would be reteamed for

Whatever Happened to Cousin Charlotte?

"Yes, we are are making

another

picture together," Bette told reporter Wanda Hale. "I like to work with Joan. She's a

real

pro, serious about her acting, always on time, always

prepared.

So different from some of these new young people, some of whom are stars but still not pros."

Budgeted at $1.3 million, Twentieth-Century Fox agreed to finance and distribute the new film, with Aldrich and the studio equally dividing all future profits, after negative and distribution costs and the payment of profit participation to the players were paid. Scheduled to begin production in April, Crawford requested a postponement of one month. "April is no good for me," she informed Aldrich, "because I am due to attend the Pepsi sales convention in Hawaii that month."

"Miss Crawford was

not

thanked for this delay," said Bette. "With the heat of summer on location, she made us suffer greatly for her silly business appointments."

In preproduction, during the postponement, according to the director's files, it was Bette who then threatened to jeopardize the project by quitting completely. Early in May, in an eight-page handwritten letter to Aldrich, she said her promised partnership on the film was being ignored. She expressed her bitter disappointment that the title had not yet been changed, a cinematographer had not yet been chosen, and the original writer, Henry Farrell, had been replaced without consulting her.

"I feel I know and understand you as well as anyone," Bette wrote to the director-producer. "You are stubborn and have to be solely in charge. You do not function well with someone of my type. That was obvious throughout the filming of

Baby Jane—and

the suicidal desire this put me into many times, was almost more than I was able to bear.

"The machinations of the new film from the very beginning have been tricky. And therefore most discouraging. I do not wear well with tricks designed to make me do what someone else decides I will do. We have not been partners—and you do not intend that we will be."

Repeating her lament on the change in writers, Bette said it was done surreptitiously, without advising her ("It is incredible that you forget I have friends who care for my welfare and keep me informed"), and she found the new script appalling. She knew what the director was up to: he was trying to trick her into playing a repeat of their last film. "You will do your best to do a remake of

Baby Jane.

No matter what I look like on the set—you can order the cameraman to 'Fix me up.'

"I could never trust you again," she concluded. "There is no going back. I truly do not feel I can work with you again. If you are wise for the good of the film you will re-cast and pay me off. It will be cheaper in the long run."

Responding with flowers and an apology, Aldrich quickly induced Davis to stay, but again he was forced to make some adjustments in her contract. Early in May he confirmed in writing that the billing of the film would show her name on the same line as Crawford. "Both the same size. Yours on the right. Joan's on the left, with an asterisk to show 'In alphabetical order,'" the producer promised, and, to validate her worth as a consultant and an unofficial partner, he would give her an additional 15 per cent of 100 per cent of net profits (the same cut as Joan), with Twentieth-Century Fox assuming 10% of that payment.

On May 14, with a firm start-date agreed upon, Fox held an open party to reintroduce the stars and the director to the press. Bette arrived on time, with Bob Aldrich. Joan arrived precisely fifteen minutes late.

"This isn't going to be

Baby Jane

strikes back. It's altogether a different picture," Aldrich told the assembled reporters.

"Yes," said Bette, "it's a whole new story. Miss Crawford and I are not doing an Andy Hardy series."

"I am not in a wheelchair this time," said Joan. "I will be very active and appear more attractive I might add. My character works in public relations in New York, which means I will get to wear some beautiful, expensive clothes. Right, Bob?"

"Certainly, Joan."

"And I will be singing the title song in the picture," said Bette, "accompanied by a harpsichord. It will be

quite

lovely."

"What about the billing?" a reporter asked.

"We tossed a coin and Miss Crawford won," said Aldrich.

"There will be an asterisk beside Joan's name and one beside Bette's," a publicist hastily spoke up. "The asterisk reads 'in alphabetical order.' "

According to

Motion Picture,

enmity between the two stars erupted anew on day one of the costume fittings, when Joan arrived and found she was barred from the set, where Bette was testing her wardrobe and makeup. "Comparative testing is important for contrast," said the magazine. "If one star is wearing her hair down, the other will probably wear it up. If one wears pink, the other certainly is not going to wear pink."

When Joan complained to Aldrich, he asked his "partner," Bette, to call and mollify her costar. "What does it

matter,

Joan?" said Bette, attempting to ease Joan's paranoia. "I am going to be a

mess,

and you are going to look your usual gorgeous self."

"Dear Bette," said Joan, comforted for the moment.

On May 18 the cast showed up for the first day of rehearsals, on stage six at Fox. For an opening-day gift, Joan gave Bette a huge box, tied in ribbon, of kitchen matches, the kind that Bette liked to strike on her shoe or rear end. Bette sent Joan a thank-you note.

At the first reading, closed to the press, Bette was sitting at the round table, hunched over, with her glasses perched on her nose, when she noticed that "Madame" (Joan) was preening unduly. Up in the flies, in the catwalks overhead, the star had sensed there was a photographer recording the proceedings.

Charlotte rehearsals, with Joseph Cotton

"I asked Aldrich if I could take some shots," said Phil Stem. "He said, 'No way, you son of a bitch. I have enough trouble with the two dames.' I kept pleading. I told him my coverage of the

Baby Jane

rehearsals brought him good luck. He said 'OK, but, damnit, keep out of our way and don't let the ladies see you.'"