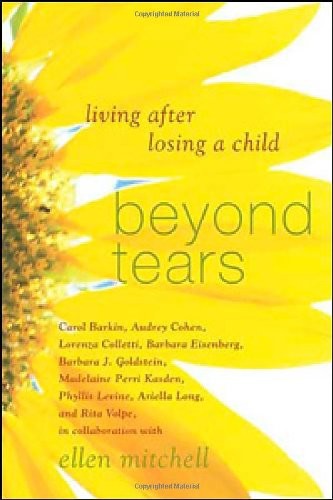

Beyond Tears: Living After Losing a Child

Read Beyond Tears: Living After Losing a Child Online

Authors: Rita Volpe

BOOK: Beyond Tears: Living After Losing a Child

5.51Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

In Memoriam

JESSICA COHEN 1979–1995

(daughter of Audrey and Irwin Cohen)

(daughter of Audrey and Irwin Cohen)

MARC COLLETTI 1968–1995

(son of Lorenza and Joseph Colletti)

(son of Lorenza and Joseph Colletti)

BRIAN EISENBERG 1974–1996

(son of Barbara and Michael Eisenberg)

(son of Barbara and Michael Eisenberg)

HOWARD GOLDSTEIN 1970–1991

(son of Barbara and Bruce Goldstein)

(son of Barbara and Bruce Goldstein)

LISA BARKIN GOOTMAN 1967–1995

(daughter of Carol and Donald Barkin)

(daughter of Carol and Donald Barkin)

ANDREA LEVINE 1965–1987

(daughter of Phyllis and Melvin Levine)

(daughter of Phyllis and Melvin Levine)

MICHAEL LONG 1975–1995

(son of Ariella and Robert Long)

(son of Ariella and Robert Long)

NEILL PERRI 1971–1995

(son of Madelaine Perri Kasden and John Perri,

stepson of Clifford Kasden and Mary Speed Perri)

(son of Madelaine Perri Kasden and John Perri,

stepson of Clifford Kasden and Mary Speed Perri)

MICHAEL VOLPE 1967–1987

(son of Rita and Thomas Volpe)

(son of Rita and Thomas Volpe)

Table of Contents

T

here are certain truisms in life. One of them is that it goes against the natural order of things to bury one’s child. However, as bereaved mothers we can no longer believe in natural order. Our comfortable, secure lives, our innocence, all were shattered with the deaths of our children. Now our reality is upside down, inside out and far removed from what we thought it would be.

here are certain truisms in life. One of them is that it goes against the natural order of things to bury one’s child. However, as bereaved mothers we can no longer believe in natural order. Our comfortable, secure lives, our innocence, all were shattered with the deaths of our children. Now our reality is upside down, inside out and far removed from what we thought it would be.

Each day is a learning experience in a course we never signed up for, in a life we never anticipated. Along the way, we have each acquired some degree of healing, and we have reached a point in the road where we can now share what we have endured. We hope our stories will shed some light for others who find themselves walking the same dark path.

This, then, is a book that no one ever envisions needing. It talks of how we wake each day and pass the hours when there seems scant reason

to do so. It tells of how we go on when going on appears pointless, and it explores ways in which we manage to exist when our lives seem hollow and we are left to wonder … why me? Why my child?

to do so. It tells of how we go on when going on appears pointless, and it explores ways in which we manage to exist when our lives seem hollow and we are left to wonder … why me? Why my child?

We are nine women of similar backgrounds; we all lost children who were teens or young adults. They died as the result of either illness or accident. Although we had never met before our sons and daughters were taken from us, we eventually gravitated to one another as we searched desperately for understanding.

Now we are a large part of each other’s lives. We meet regularly for dinner. We endure mutual pain. We phone each other at all times of day and night. We sit together for hours—listening, writing, reading and listening some more. As a group, we revisit places that others have long forgotten, but which we cannot bear to leave behind.

We have survived in concert with one another, even when we were in such deep despair that we wondered if our lives were worth living and contemplated suicide. We leaned on one another when we could barely place one foot in front of the other if we had tried to stand alone. We owe our inner grit and spirit to the fact that we have shared our ordeal and bonded together.

We have discovered the sad truth that beyond our own circle there is very little realistic and substantive help for those who grieve for the loss of a child. We have each found a crushing lack of awareness and understanding among many whom we should have been able to depend upon such as medical personnel, clergy, social workers, bereavement counselors and in some cases even family and friends.

In this book, we share the practical approaches we take when people fail to be of help. We tell how we have learned to get through holidays and what used to be joyous family occasions. We discuss the changes that have occurred in our relationships with our spouses, our other children and the entire family dynamic.

We also voice our opinions of those who take their cue from the pop culture of our times to tell us it is time for us to “get on with our lives” and find “closure.” Indeed, since the horrors of 9/11, “closure” seems to have become the watchword of therapists, politicians, journalists

and television analysts alike. These “civilians,” our name for those who have not experienced the death of a child, have no idea what they are speaking about when they use this term. We the experts know all too well that there is no such thing as “closure” following the senseless and untimely death of a child.

and television analysts alike. These “civilians,” our name for those who have not experienced the death of a child, have no idea what they are speaking about when they use this term. We the experts know all too well that there is no such thing as “closure” following the senseless and untimely death of a child.

We have much to share. We know the value of a day’s work in order to keep our thoughts from becoming mired down in our personal tragedies. We have learned how to react when a stranger asks, “How many children do you have?” We share what we do when a longtime acquaintance crosses the street to avoid the uneasiness of having to chat with us.

We know how hard it is to face our dead child’s bedroom and his or her favorite breakfast cereal. We deal with demons that come in the night and clumsy neighbors who come in the day. We memorialize our children by wearing their jewelry and by setting up foundations in their names.

Because it is our hope that this book will be read by grieving couples and their family members, as well as counselors, clerics and others, we have included the views voiced by the fathers of our children. Much as we women have been there for each other through the years so, too, our husbands have become well acquainted and supportive of one another. In some ways, their manner of experiencing and expressing grief parallels our own, but in other respects is in marked contrast to our own.

While our stories are different in detail, they are similar in sum. Many of you probably have stories and needs much like ours. We know we can be a source of comfort to you. We have found there is much to be gained in just realizing there are others who have experienced the same horror and felt, as we all did, that they would not be able to keep a grip on their sanity.

There is no clear road map for passing through parental bereavement. However, there is a path that takes us from relentless grief to what we now call “shadow grief.” “Shadow grief” is always with us, but it is bearable. We are helping each other along that path.

It is our love for our lost children that has given us the inspiration, the strength and the determination to put our thoughts and our words into book form. We have to believe our children made a difference in their far too short lives on this earth. They are with us every step of the way, and it is their memory and guidance that has helped us to develop this book, in which we share with you some of what has helped us to get beyond our tears.

JESSICA RACHEL COHEN

Jessie was my only child, not that that makes her story any more or less important than the others—that’s just the way it was.

Funny, but I always thought of her birth date, 7/11, as my lucky number, and I guess it was … just to have had her for those years. It’s the only way I can think. After she died, we learned that a great many others whose lives she touched in her short life felt just as we did.

As far back as nursery school, Jessie knew who she was and where she wanted to be. She was never bored; life was her playground. She was content to be by herself, and she was just as content hanging out with her friends. She was interested in everything and loved learning. At parent-teacher conferences she made me proud. I loved being Jessica’s mom.

Jessie’s faith in nature was boundless. At the age of four, she asked my husband, Irwin (we call him Irv) if she could plant a kernel of popcorn. He explained that the kernel was overprocessed and could not possibly grow. Not to be thwarted, she dug a small hole and planted a single kernel smack in the middle of our backyard. Irv spent the rest of the summer mowing around the corn that sprang up in the midst of our lawn.

Jessie could pop the seedpods of impatiens plants or make an impression of a leaf using sunlight on photo-sensitive paper. She planted watermelons, cantaloupes and splashes of colorful flowers, among them the bleeding hearts that still bloom and tug at our heartstrings every spring. All these years later we continue to reap the fruits of Jessie’s garden.

In high school, Jess oversaw her school’s video production program. She was always behind the camera, according to her television production teacher, who described Jessie as “one of the greatest kids I have ever known.” Today there is an annual video production award given to a deserving student because of a memorializing fund set up by that teacher.

I know I am a doting mom, and I don’t want to leave the impression that Jessie was perfect … far from it. But she was a very special treasure.

Jess was poised and confident. She had a beautiful, though untrained, singing voice. She played the guitar, she played softball, she was a member of Mathletes, her school’s competitive math team, and from the fifth grade forward, when she first came to know the story of our country’s founding, she dreamed of becoming an American history teacher.

Jess was poised and confident. She had a beautiful, though untrained, singing voice. She played the guitar, she played softball, she was a member of Mathletes, her school’s competitive math team, and from the fifth grade forward, when she first came to know the story of our country’s founding, she dreamed of becoming an American history teacher.

She was patient and kind, and possessed strong convictions and a beautiful sense of decency. She was a true friend but fiercely independent. Who but a teenager with a quirky sense of humor would teach their dog Clyde to communicate? She would surreptitiously tickle his neck so that he appeared to be shaking his head no in response to questions, usually of the “do you like so and so?” variety.

It all ended on June 30, 1995, when Jessie was eleven days shy of her sixteenth birthday.

We were visiting my husband’s sister and her husband in the Poconos. We had driven up the night before and stopped at my stepdaughter’s home. Irv had just taken retirement from Grumman, and Jess had just finished her sophomore year. A friend of hers, Krishma, was along with us.

It’s odd the things you remember afterward. I remember Krishma and Jessie sitting in the backseat of the car talking, and Jessie asking Krishma, who is of the Sikh faith, how anyone could agree to an arranged marriage. Krishma told her you just accepted what your life was supposed to be. I don’t know why I remember that.

We were up early that morning. It was so peaceful. We watched a family of deer grazing in the woods behind the house. Jessie was feeling good and she made breakfast for everyone. Our conversation turned to what we wanted to do that day. Someone suggested golf, someone else said shopping. Jessie wanted to water-ski. My brother-in-law had a small boat and a pair of water skis that Jess had tried a couple of times before. I think she had stood up on them for a split second once, but she was never able to stay up. We decided to take her waterskiing early, before the July 4 weekend crowds arrived.

My sister-in-law and I stayed onshore because my brother-in-law thought too many people in the boat would make it harder for Jessie to

get up on the skis. We played Scrabble, and in the distance I could see Jessie and Krishma swimming near the boat. Then I didn’t see them anymore. The lake was still and almost deserted.

get up on the skis. We played Scrabble, and in the distance I could see Jessie and Krishma swimming near the boat. Then I didn’t see them anymore. The lake was still and almost deserted.

At one point, I did see someone water-skiing and I jumped up and asked, “Is that Jessie?” My sister-in-law said, “You’re always so nervous.” But I just didn’t feel right. I was jittery, maybe because I was never comfortable in the water. Not like Jess. She was a good swimmer. She had no problem with the water.

We had been there an hour or so when the boat pulled up and my brother-in-law was yelling, “She went down, she was hit. Call 911, get an ambulance!” I thought he was kidding, then I realized he wasn’t. I didn’t know what to do first. Should I run to the boathouse? Should I go to Irv? I pounded on my brother-in-law’s chest because he didn’t want me to go to Jessie. But I ran to her anyway and she was just lying there in the boat. I started screaming, “Please, Jessie, please, don’t die.” Irv, who had dove in and pulled Jess out of the water, was telling me there was no pulse, no breathing … nothing.

Jessie died when she was struck by a jet ski propelled by a mentally and physically challenged young woman who was left unsupervised. Her father later said he was sure he had locked the watercraft securely. But we don’t believe that. We never had a personal word from that young woman’s family, no letter, no apology. I can’t forgive that.

Maybe if someone else had been driving the boat. Maybe if I’d been out there. Maybe I could have seen something, done something. You turn the story over and over in your mind.

After Jessie’s death, at her high school memorial service, her English literature teacher said of Jessica, “Because she was in my life, I am a better teacher, a better mother, a better friend, a better person. She will unquestionably live forever.”

Would that she had.

Audrey Cohen

Other books

Palaces of Light by James Axler

F Paul Wilson - Novel 05 by Mirage (v2.1)

The Gordian Knot by Bernhard Schlink

Saffire by Sigmund Brouwer

Like a Wisp of Steam by Thomas S. Roche

The Torrid Zone (The Fighting Sail Series) by Alaric Bond

Kismet (Beyond the Bedroom Series) by Pittman, Raynesha, Randolph, Brandie

Shifters Unbound [5] Tiger Magic by Jennifer Ashley

The Great Depression by Roth, Benjamin, Ledbetter, James, Roth, Daniel B.

The Governess Affair by Courtney Milan