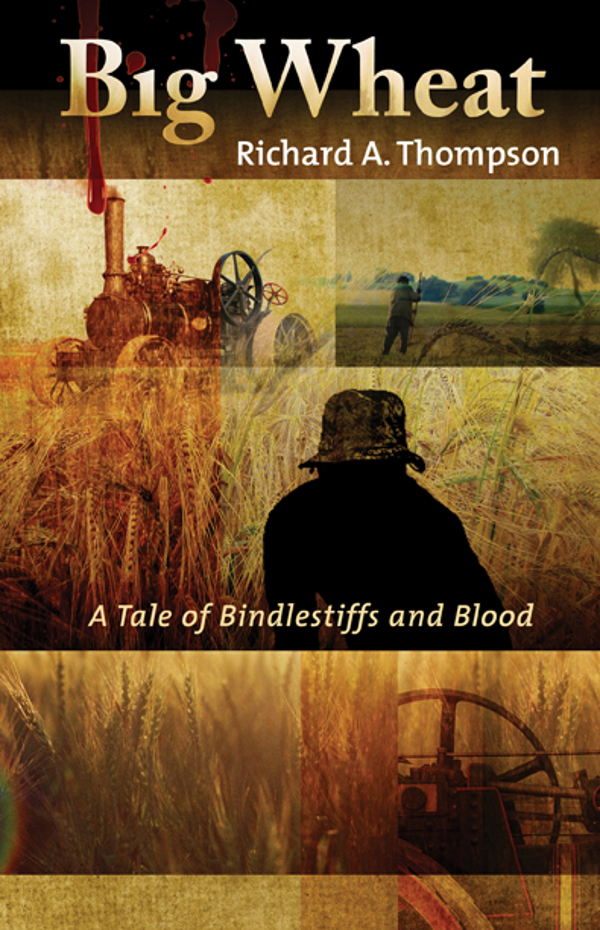

Big Wheat

Big Wheat

Copyright © 2011 by Richard A. Thompson

First Edition 2011

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2010932088

ISBN-13: 978-1-59058-820-8 Hardcover

ISBN-13: 978-1-59058-822-2 Trade Paperback

ISBN-13: 978-1-61595-244-1 Epub

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in, or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise) without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

Poisoned Pen Press

6962 E. First Ave., Ste. 103

Scottsdale, AZ 85251

For Caroline

…a true daughter of the prairie

Contents

Once again, I am enormously indebted to my astute and trusted beta reader, Margaret Yang, without whose input and encouragement, this project would have died more than once. A million thanks, precious friend. Keep the faith.

Many thanks also go to Professor John Fraser Hart of the University of Minnesota, for his very helpful insights into the history and evolution of the American farm and to Brenda Stant, publisher of

Engineers and Engines

, for helping to keep the references to bygone machinery accurate.

The threshing era was a unique period, perhaps the only time in modern history when the application of industrial technology to a traditional way of life actually brought people closer together, rather than isolating and estranging them. A threshing operation needed the labor of the entire rural community, in addition to that of several outsiders and a lot of machinery that few individual farmers could afford to buy on their own. Hard work notwithstanding, the event took on the air of a carnival, a family reunion, and an interdenominational faith rally, all rolled into one. It was the social event of the year. I believe it is for this reason that the practice of the threshing bee persisted until the end of World War II in some areas, decades after newer technology had rendered it unnecessary.

As a very young child, I lived on a farm in southeastern Minnesota, which is neither Corn Belt nor Wheat Belt but a close cousin to both. I vividly remember the last threshing season there. Though I wasn’t allowed very close to the action, I could feel the energy and excitement of it. And as I got older, I instinctively collected harvest stories, some of which are included in this book.

In order to better transport myself back to that time and farther, I have freely borrowed the names of many of my childhood relatives and neighbors. But only the names. All characters in this book are entirely products of my imagination and bear no resemblance to anyone I have ever known, seen, or heard of.

The town of Ithaca, the not-quite town of Hale’s Corners, and the Unitarian church in the middle of the prairie are fictitious. All other settings in this book are real and as accurate as I could make them, as they would have appeared in 1919. The machines are also real, as are the background news events and the topical opinions of the day. As thoroughly as I could, I wanted to recapture that world.

Welcome, then, to the world of the steam traction engine, the threshing machine, the bindlestiff, and ultimately the high road to the Dust Bowl. Welcome to the world of Big Wheat.

Graveyard Shift

Late August, 1919

Somewhere on the North Dakota prairie

The harvest moon was down to its last sliver, feebly backlighting the wrinkled gray crepe that hid the stars. But for the man with the pick and shovel, it cast light enough. He had dug many graves in the hard soil of the high plains, most of them in the dark. He was an old hand at it. He occasionally used a hooded lantern to check his progress or reorient himself, but he really didn’t need it. He could do the job with his eyes closed.

It didn’t have to be as deep as a real grave, only deep enough so that the coyotes or stray dogs couldn’t dig the body up, and the spring plows would glide harmlessly over it. Waist high was good enough, two or three hour’s work. He threw the dirt all to one side of the hole, away from the mountain of straw from the day’s threshing operation. The straw pile screened him from the farm buildings a quarter mile away and gave him a sense of security and privacy.

He looked down at the dead girl and decided the hole was big enough. She was so pale that even in the dim light, he could clearly make out her naked body. The eyes that had so recently shed tears of despair were now frozen in perpetual horror. The mouth that had tried to scream was slack and shapeless, just another dark gash to match the many others, where he had bled her to purify the earth.

And the earth needed so very much purifying.

He rested for a moment, leaning on the shovel handle, and looked across the field of stubble, just starting to be covered by a thin layer of ground fog. For hundreds of miles in every direction, he knew, it was the same: the land of the buffalo, the land of the cowboy, the land of the billowing prairie grasses, all torn up, leveled, plowed, planted and plucked. God’s prairie had been beaten into a money factory. It was more than just wrong; it was obscene. Sooner or later, he was absolutely certain, both God and the earth would have their revenge. But until that day, he preserved some semblance of balance in the universe. He watered the ground with blood. He atoned for all the folks who were too self-satisfied or stupid to do it for themselves. He was the last virtuous man on the high plains, and he was virtuous enough for everybody.

“You must have broken a lot of hearts with those big doe’s eyes,” he said to the corpse, “and that pouting mouth that just begged to be kissed.” And that, of course, is what had made her such a good sacrifice; many people would mourn her loss. He felt a slight lump in his pocket from the locket he had taken from her, and he snorted at the thought of it.

“What kind of a person has her own picture in her locket?” And also her name, professionally engraved. He didn’t usually know the names of his offerings.

He mentally chided himself for speaking out loud, but he was feeling expansive. He had done such a fine job, after all.

The fog was beginning to drift down into the open grave. He threw the body in and shoveled the dirt on top of it. He took his time, tamping down all the loose corners, leaving no soft spots to settle and call attention to themselves. When he was done and the whole area was stamped down thoroughly, it was just slightly higher than the surrounding ground. It was also noticeably cleared of mown wheat stubble, but that would not be a problem.

He put the shovel and pickaxe off to one side and picked up his other tool, a pitchfork. From the huge pile next to the grave, he pitched straw on top of the dirt until it was covered to the depth of his knees. In the morning, the nearby threshing machine would be cranked up once again, the job of harvesting the field would be finished, and the pile of discarded straw would be even bigger. Then the machine would be moved away and the pile would be set on fire. And when there was nothing left of it but smoldering ashes, nobody would notice or care if there was a break in the stubble pattern. It had worked before, many times. It would work again. He had been purifying the land since 1914, when the people of Europe had started purifying their own overworked fields with lakes of blood. Their work was finished now. He didn’t think his would ever be. It was good, having a vocation.

He admired his handiwork one last time, then put out the lantern, picked up his tools, and had a last look around the flat landscape. And froze.

Ten yards away, a man stood looking at him, saying nothing. He was tall and solidly built, but lean, with the easy erect posture that only comes with youth. He had light-colored, possibly even white hair that hung down on his forehead and a heavy pack on one shoulder. He did not move. There was no way to guess how long he had been there.

“Do I know you?” said the young man. He sounded confused, quiet, mumbling.

“No.”

“I think I—”

“No.”

The gravedigger began to back away slowly, moving into the black shadow of the straw pile. He had no qualms about killing the stranger, but he had no advantage of surprise and no edge of any other kind, either. And he made it a point never to attack anyone unless he had an edge. He took several more cautious steps backward, and when the stranger didn’t follow, he bundled his tools on his shoulder, turned, and walked into the welcoming vastness of the dark prairie.

He walked with a slight limp, the memento of his father’s older brother. When he was eleven, the uncle had grabbed his foot as he was sitting on the family couch and had twisted it, saying, “Who’s the best uncle in the world?” When the boy said nothing but “Ouch!” he had twisted harder. Finally, the boy called him the worst name he knew, and the man twisted until something snapped, bathing him in excruciating pain. Nobody took him to a doctor. He wasn’t important enough to be worth the money.

Three months later, he had limped across the newly plowed Kansas fields by the light of a gibbous moon and had set fire to the uncle’s farmhouse. He waited by the front door with a hickory axe handle cocked on his small shoulder, ready to bludgeon anybody who tried to run out. But nobody did. Years later, when a sharp winter wind or a severe storm front sent sudden pangs of pain shooting up his bad leg, he would remember the screams that had come from the second-story bedroom window of the burning house, and smile. It had been his first experience with righteous killing. The memory was good.

Wandering Son

The way Charlie Krueger’s life was going, the strange man pitching worthless straw in the moonlight barely rated a second glance. Four days earlier, the only woman he had ever loved had taken his heart in her soft white hands and broken it like a twig.

Her name was Mabel Boysen, who pronounced her first name as if it were spelled Mae Belle and who had a thousand other little quirks and vanities that made her the most desirable young woman who had ever walked the earth. She grew up three farms over from the Krueger place, a mile and a half of country lane away. They met in the fields as small children, sent to pick wild mustard plants out of the growing oceans of oats or barley. They saw each other on the main street of Hazen on Saturday nights when their parents came to town for supplies, and in the Lutheran church on Sundays. They winked over the pews at each other and made hand-signal jokes about the day’s sermon. And eventually, they met secretly as lovers. In the hay loft of Hans Buck’s barn, which was midway between their own farms, she taught him something she called a “French kiss,” which he found strangely wonderful. “And it doesn’t leave a hickey,” she had said.

A few days later, they had met in the waist-high wheat fields, in broad daylight. As she approached him, she locked her eyes on his, smiled her loveliest smile, and pulled off her dress and underclothes and threw them aside. Then she wrapped her arms around his neck. He was too astonished to know how to react.

“Have you ever seen a naked woman before, Charlie?”

“Um, ah, sure.”

“Really?”

“Well, no, to be honest. I just—”

“You can look as much as you want. I don’t mind.” She stepped back half a pace and spread her arms out. “But you have to take your own clothes off, too.”

He hesitated, and she stepped up to him and began to undo his shirt buttons. “Don’t be shy, Charlie. I know what an aroused man looks like. And there’s something I need you to do for me.”

He was amazed that he didn’t lose his erection from sheer embarrassment. But Mabel was not embarrassed at all. With calm self-assurance, she taught him how to caress her body, where to put his hands, how to tell when she was ready for him. And how to enter her, of course, make her wet with his seed, giving her a solemn promise that mere words could never convey. Had she made any promises? Had she even said she loved him? Surely she must have, but he couldn’t remember. What he did remember was her saying, “We shouldn’t meet at the same place more than once. I’ll pass you a note in church, tell you where to go next time.”

And there had been many next times, each one more wonderful than the last. The other things, the questions of her love and her promises, he put out of his mind. Sometimes he was very good at putting things out of his mind.

What he did put in his mind was that they were Romeo and Juliet, Tristan and Isolde, Cinderella and Prince Charming, but without the castle or the kingdom. They were the most wonderful love story in all of history, and they were surely destined to be married and live happily ever after. His father had said he intended to give the family farm to Charlie’s sister, but what of it? He said a lot of mean things to Charlie, especially since Charlie’s brother had died. Charlie was sure if he took a fine wife, the old man would change his mind. In some dim corner of his mind, he felt that the farm shouldn’t matter, anyway. He and Mabel should have many adventures all over the world before they settled down to raise beautiful children in some city. He didn’t know what city, but he thought it should be a big one. Big cities had big opportunities.

But Mabel got very distant when he talked like that. She thought cities were evil, impersonal places. He dared not displease her, so he dropped the topic. Even more than he feared the erratic and often irrational wrath of his father, he feared her tiniest displeasure. So for an entire, blissful spring and high summer, he settled for dreaming of being married to the most beautiful woman in the world. If that also meant he had to be a farmer, well, that would somehow work out.

Then Mabel got pregnant. She told him with a huge smile, in the shade of a small walnut grove where they sometimes met. He took it calmly. It was a simple piece of information, natural enough, without any real emotional impact. He had always intended to have children with her. Now, the sequence of their lives would be different than he had expected, but nothing else would change. After all, they were in love. Didn’t love make everything work out?

Mabel Boysen, woman in charge, woman who knew exactly what she was doing and exactly what she wanted, was delighted with her own news, but not at all for the reasons he might have imagined.

“Now I can make Harold Bow marry me,” she said.

“Why on earth would you want to marry Harold Bow?”

When I’m the one who loves you more than life itself

. The thought was so obvious as not to need stating, not that it would have mattered.

“Because he’s the oldest Bow son, of course, and his family has a whole section of land and their name on a brick in the church. You’re a good time, Charlie, but you can’t give me any of that.”

“But he’s an idiot! He has buckteeth and bad manners, and he couldn’t pour piss out of a boot with instructions written on the heel! I can’t believe you’d give him the time of day.”

“He’s also probably sterile, but he doesn’t know that. You’ve been a lot of help, Charlie, and really, really sweet. I can’t thank you enough for giving me your child.”

“Giving you a child? But I mean to give you a whole life! I love you, Mabel. How can you not know that?”

“That’s a silly word.”

“Love is a silly word? But you—”

“No, Charlie, you never heard me use that word. You men get all confused when you’re in heat. All I ever said was there was something I needed you to do for me. And now you have, and I’m very grateful. But if you ever say a word about it to anybody, I’ll have to accuse you of rape, and then you’ll get run out of the county on a rail or lynched or who knows what. Just be happy that we had some good times and that there will be a beautiful little girl who will be just like you.”

“How do you know it will be a girl?”

“Silly Charlie. Because that’s what I want. And I always get what I want, don’t I? But don’t be sad. Maybe in a year or so I’ll need your help again.”

He turned and walked away from the grove without another word. If he had stayed, he might have wound up hitting a woman, or worse yet, crying in her presence. He felt as if he had been shot in the gut with a cannonball made of ice.

That night he decided to leave home, though he didn’t yet know where he would go or how he would live. His present life was intolerable, but any other he could think of was terrifying. At some level, he felt as if he had been holding his breath for years, waiting for an opportunity such as this. The only thing tying him to this piece of land and to the father who constantly insulted and abused him had been his love for Mabel. Now that he had lost that, he could do whatever any adventurous young man would do. He tried to see that as a good thing. He couldn’t.

He assembled a traveling pack, including all the military gear his brother had sent him that he had never expected to need. He had a folding field compass and a fine, canvas-covered quart canteen and a real bayonet in a belt sheath and a new kind of mechanical cigar lighter, for which he had not yet been able to buy fuel. Kerosene, he had found, did not work well at all. He also packed a seven-millimeter Luger pistol. He didn’t know if his brother had taken it off a dead German officer whom he had personally killed, or merely picked it up on the field of battle. If the stories he had heard about the carnage were true, it might have been hard to tell the difference. In any case, soldiers were allowed to ship packages back home free of charge, and a small tidal wave of war souvenirs was the result.

Lugers were highly prized. There were sevens and nines, his brother had written him, and they had opposite magazine sizes. The seven millimeters held nine bullets and the nine millimeters only held seven. Plus one in the chamber, of course. But he didn’t have an extra bullet, only a single loaded magazine. It would have to be enough. How dangerous could the high prairie be, anyway?

All this and more, Charlie assembled into the makeshift backpack, including a shovel with a broken handle. The next day, he rose even earlier than usual to feed the livestock and milk the family’s four cows. After the milking, he put out a battered pie pan full of milk and stale bread crusts for the pack of semi-feral cats who lived somewhere in the barn and kept it free of rodents. He always smiled as he put down the pan, because his father had sternly forbidden the practice. He put the rest of the milk in a galvanized steel can and put the can in a tank of cool water in the well house, where a windmill kept it full. Then he harnessed the horses. It was the start of threshing, and the day would be a long one.

He did his part to bring in the annual Krueger harvest, driving a team of horses pulling a reaper/binder, and the next day sacking the clean grain that was coming out of the Red River Special separator and hauling it away with a different team. It was a duty he felt he owed, even though he knew he would not share in the bounty. You weren’t much of a son if you didn’t help with the harvest.

“Was it a good harvest, Robert?” said Charlie’s mother at supper that night.

“Pot liquor,” said his father, with sneering venom. “Can’t make no money off a piddling hundred acres. If Bob, Junior, hadn’t a got his self killed in that damn war, I could buy some more land and raise enough wheat to make some real money. But with just Charlie? Ptah! Now if Charlie’d been the one to die—”

“Then you still couldn’t get rich,” said Charlie, “because you’d still be out in the barn getting drunk half the time.”

His mother and sister gasped. No one ever dared raise that topic.

“What did you say to me?” He rose from his chair, slowly, seething with rage and radiating menace. “You don’t talk to me like that, you young snot. Not now and not ever. I’ll take my belt and whip you into next month, is what. First, though, you gotta know you ain’t having no supper in this house.”

They had played this exact scene before, many times, sometimes for some trivial reason and sometimes for no reason at all. Charlie remembered the beatings out in the barn, starting in early childhood, and how he had felt belittled and somehow cheated as much as physically hurt. And suddenly he realized that all of the beatings, whatever their stated excuses, had a single purpose: to make his father feel important by making Charlie permanently afraid of him. But this time, he felt no fear.

His father reached across the table and wrapped his fingers around the rim of Charlie’s plate, dragging it toward him. Time stood still, and Charlie stepped outside himself. As if from a vantage point somewhere at ceiling height, he saw himself pick up the carving knife from the meat platter and stab it viciously down on the fleeting plate of food. Meat and potatoes flew in every direction, the heavy plate snapped in two, and the knife pinned his father’s hand solidly to the wooden table. He let out a cry that was not quite a word and looked at his son in astonishment. He trembled as he tried to pull the knife out. It didn’t budge.

Nobody was more shocked than Charlie. But fate and reflex and a whole ocean of pent up anger had taken charge, and he didn’t see any way he could retreat.

Might as well be hanged for a goat as a lamb.

“You’re all done taking things away from me, Pa. And you’re all done beating me, too.” He came around the end of the table and wrapped his own belt around his knuckles.

“I’ll kill you, you worthless piece of—”

“Just as soon as you get your hand free? Then I’d be stupid to wait, wouldn’t I?” He stepped behind his father and hit him on the ear, so hard it snapped his head down onto his shoulder. Charlie drew back his arm to do it again.

“No! Please, Charlie! No more! I didn’t mean none of that stuff, I swear.”

“Swear to somebody else. I’m leaving.” He was amazed at how easy it was to say that. For years, he thought he’d never be able to stand up to his father’s bullying. But now that he had done so, he couldn’t imagine what had taken him so long. He put his belt back in his trouser loops. To his mother, he said, “I don’t suppose you could go to the trouble to make me some sandwiches?” She fled to the kitchen with obvious relief.

He collected his pack from his room, then came back to the dining room to say goodbye to his sister.

“I’m afraid, Charlie.”

“You’ll be all right, Ruthie. I put a slide bolt on the outside of the barn door last night. Next time pa goes out there and starts drinking, lock him in. In the morning, if he comes out screaming bloody murder, hit him in the head with a number ten skillet, right off.”

“I don’t know if I can—”

“Don’t think about it, just do it. Bullies are all cowards when you stand up to them. You just saw that. Anyway, you need to do it for ma, if not for yourself. If the old man starts getting after either of you anyway, send me a letter to general delivery in Minot. I don’t know where I’ll wind up spending the winter, but I’ll check there before I head farther north. If he’s not treating you decent, I’ll come back and kill him, I promise.” He said it loud enough that his father could not have failed to hear, and he punctuated it with a hard look in that direction.

“Oh, Charlie, do you really have to go? You said it yourself; now that you stood up to Pa, things will be different.”

“I have to go, Ruthie. There’s a big hole in my heart that I can’t talk about, and I have to go see if I can find a way to heal it.”

“Then be careful out there.” She gave him a tight hug.

“For you, I’ll try.”

His father had freed his bleeding hand by then and wrapped it in a kerchief, but he was still sitting at the table, whimpering quietly.

“You ain’t ever been out of this county, Charlie boy. You think life is easy out there? You think people are just dying to help out a worthless sum bitch, hits his own father? You’ll see. You’ll wind up eating out of somebody’s hog trough and sleeping in a ditch.”