Black Genesis (17 page)

THE SUN TEMPLE OF DJEDEFRE IN THE SAHARA

In chapter 2 we saw the important discovery of the so-called Djedefre Water Mountain (DWM) by the German desert explorer Carlo Bergmann. We recall that on this mountain (actually a small sandstone mound that is about 30 metersâ98 feetâhigh), which is about 80 kilometers (50 miles) south of Dakhla oasis, were found hieroglyphic inscriptions of the names of the pharaohs Khufu and Djedefre alongside prehistoric petroglyphs that contained the water sign and depictions of fauna that no longer exist in this part of the world. Naturally we might wonder, as Bergmann probably did, whether there could be a connection between the prehistoric site of DWM and that of Nabta Playa. True, nearly 400 kilometers (249 miles) separated the two places, but Bergmann's earlier discovery of the Abu Ballas Trail (see chapter 2) proved that ancient people could travel in such arid and waterless desert for much longer distances by creating watering stations along their route. At any rate, perhaps a connection between the two prehistoric sites could be established by the DWM containing evidence of astronomical knowledge that could be directly related to that incorporated in the ceremonial complex of Nabta Playa. The only way to resolve this issue was to examine DWM ourselves.

In early April 2008, the desert explorer Mahmoud Marai, a close colleague and friend of Carlo Bergmann, organized an expedition for us to visit the DWM, among other sites in the Egyptian Sahara. We started off-road near Dakhla oasis and headed south, and, after a couple of hours of bumpy riding in Marai's well-equipped Toyota Landcruiser, we reached DWM late in the afternoon. Because it was fast growing dark, we decided to set up camp and wait until dawn to climb the small escarpment that led to the hieroglyphs and petroglyphs on the east side of the mound. We were up before the crack of dawn the next day, and after a swift breakfast of hot tea and biscuits, we made our way 10 meters (about 33 feet) up the man-made escarpment and reached a platform, also man-made, that brought us level with the inscriptions.

The most prominent of the inscriptions is at the center of the east face of the mound. As we saw in chapter 2, it consists of a royal cartouche that bears the name of the pharaoh Djedefre, which is enclosed in a rectangle with two protrusions at the top that Egyptologists have assumed to be a form of the hieroglyph for “mountain” (see plate 2). As we have seen, a similar sign, but with a sun disk between the protrusions, was used to denote “horizon” or, more specifically, the Place of Sunrise. Because DWM faced eastâthe place of sunriseâit seemed to us more apt to regard this mound not as Water Mountain but rather as a sun temple. There was, however, one snag with this hypothesis: the view toward the eastern horizon was blocked by an elongated hill about 200 meters (about 256 feet) east of DWM.

This elongated hill or mesa is about 70 meters (230 feet) long and 12 meters (39 feet) high and has a flattened top with a very noticeable depression or notch in the middle. As far as we could tell, neither Bergmann nor the German scholars who studied DWM saw this hill as significant, but as we watched the sun rise over it, it became apparent to us that the hill was positioned in such a way that it would act as a sighting device for marking the yearly course of the sun and the two solstices and two equinoxes. We named this mesa Horizon Hill. Using our GPS and electronic compass, we determined that at the equinoxes the sun would rest in the notch in the center of Horizon Hill, creating the hieroglyph

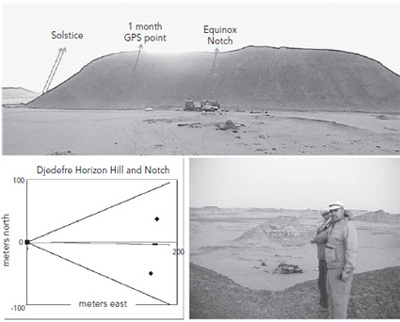

We were at DWM on April 9. We established the location as 25.40 degrees north and that sunrise on that day would be 82.09 degrees on the horizon and 83.35 degrees when breaking at 7:06 a.m. over Horizon Hill (which we estimated to be at 2.75 degrees altitude above the geometric horizon). Figure 4.13 shows the view from DWM with the sun breaking over Horizon Hill. We calculated that at spring equinox (March 21), the sun will be at azimuth 91.2 degrees when it breaks over the notch on Horizon Hill, which matches the actual azimuth of the notch as seen from DWM.

We took GPS measures in front of the central cartouche on the sun temple and also on top of Horizon Hill. On the hill we took measurements on flat areas near the north and south ends of the hilltop and at the notch near the center. The measurements we took gave azimuths of 77.9 degrees, 91.1 degrees, and 106.7 degrees, respectively, as viewed from the central cartouche on the east face of the sun temple. We also measured the flat area of Horizon Hill and determined it to be 8 meters (26 feet) higher in elevation than the central cartouche on the sun temple, and it was positioned some 170 meters (558 feet) east of the sun temple. We thus estimated that the hypothesized solar notch was at altitude 2.7 degrees above the geometric horizon when viewed on Horizon Hill. We calculate that at equinox the sun would indeed be resting in the notch at 2.7 degrees altitude and azimuth 91.2 degrees when appearing over Horizon Hill. At the summer and winter solstices and at the same altitude of 2.7 degrees, the sun would be at azimuths 63.3 degrees and 117.7 degrees, respectively. Because we photographed the notch in situ as we took the GPS point there, our measure of the azimuth of the notch is very precise and accurately coincides with the equinox sun when it breaks over Horizon Hill. Yet we recognize that our azimuth measurements of the solstice sunrises at the north and south edges of Horizon Hill are less precise, because we did not have an independent calibrating marker. On a future visit we hope to refine our measurement of the two edges of Horizon Hill with respect to the solstice paths of the sun.

Figure 4.13. Sunrise over Horizon Hill at Djedefre sun temple, April 2008. Top: the rising azimuths at equinox over the notch in the hill and the approximate solstice rising azimuth. Lower right: Brophy and Bauval standing, before sunrise, at Horizon Hill notch and pointing to the east, facing the Djedefre cartouche. Lower left: the three GPS points taken at the top of Horizon Hillâat the notch and two central hilltop locationsâthe azimuths to sunrise over the notch from the Djedefre cartouche, and the solstice sunrises.

It seems very unlikely that the emissaries of the sun king Djedefre, who had come to this place and probably stayed for extended periods of time, would have failed to note that Horizon Hill functioned as a natural solar calendar. If such a conclusion is correct, however, it would mean that, in all probability, the same was noted by the prehistoric people who had also stayed here. Was there any evidence of this? In light of this probability, we must re-examine some of the inscriptions and engravings on the mound.

Other than the Egyptian hieroglyphs and petroglyphs of fauna and other symbols, there are also arrows carved on the east face of DWM that conspicuously point upward, as if inviting an observer to look at the zenith of the sky. These arrows appear to be prehistoric rather than Old Kingdom Egyptian, because of their style of inscription and because near them are images of animals that could not have been present in Old Kingdom times. Today the site is a little less than 2 degrees north of the Tropic of Cancer, but in ancient times it was a bit closer to the Tropic line, so that each year at summer solstice the sun would pass almost directly overhead at noonâthat is, near the zenith. Could it be that ancient Egyptians of the Old Kingdom, during the reigns of Khufu and Djedefre, came here and rediscovered a prehistoric sun temple, which they then transferred to their own solar hieroglyphs? Judging from the evidence, this would seem the most likely scenario.

Within the central engraving, there is a finely rendered glyph found under the two peaks representing the horizon, or the Place of Sunrise. The lower part of that glyph appears like hieroglyphic determinative S12 by Gardiner's system,

*31

which indicates gold/white gold/ silver; the upper part of this glyph is composed only of three flag poles or standards, which we speculate may represent the three stations of the sun on the eastern horizon: the two extreme stations marking the solstices and the midstation marking the equinoxes. When we view the eastern horizon from DWM, these three stations are marked by the extreme ends and midpoint (the notch) of Horizon Hill. And visually this rendering of S12 seems reminiscent also of the cosmogonic solar barge said to carry the sun across the sky, and usually carrying one or more deities, yet here it carries the three stations of the sunâwhether the original artists intended this visual metaphor, we don't know. Unfortunately, we could stay at DMW only a few hours before moving on to other destinations planned by our expedition. Still, we hope that our findings there will now encourage anthropologists and Egyptologists to look for more direct links between this mysterious place and Nabta Playa.

BAGNOLD CIRCLE

We next headed southwest into the deep, open desert. Our destination was a mysterious stone circle discovered in 1930 by Ralph Alger Bagnold and thus known as Bagnold Circle. The stone circle was poorly documented and very little was known about it, but photographs encouraged us to suppose that it, too, like the Calendar Circle at Nabta Playa, could be some sort of prehistoric astronomical device.

Figure 4.14. Bagnold Circle in, top, 2008, and bottom, 1930

It took us two days of grueling travel in some of the most desolate places we had ever seen to reach Bagnold Circle. We wondered how Ralph Bagnold, in those days with vehicles that must have been very primitive by comparison, managed to come here through this testing terrain. Bagnold, who was a veteran of trench warfare in World War I, became a pioneer of deep desert explorationâespecially, of the Saharaâthroughout the 1930s. During World War II he was chosen to lead the British army's Long Range Desert Group. He was also a physicist who contributed valuable knowledge of the physics of blown sand, which is still used in planetary science research

today.

30

He is credited with developing, for desert exploration, a sun compass that was not affected by magnetic anomalies. Bagnold's early expeditions in the Egyptian Sahara were in search of the fabled lost city of Zarzoura. It was on one such expedition in 1930, when he was traveling in the deep desert hundreds of kilometers southwest of Dakhla oasis, that he reported: “In a small basin in the hills we came the next day [October 27, 1930] upon a circle 27 feet in diameter of thin slabs of sandstone, 18 to 24 inches high. Half were lying prone, but the rest were still vertical in the sand. There was no doorway or other sign of orientation, and though we searched within and without the circle, no implements could be

found.

31

As we approached Bagnold Circle, we were keenly aware that no studies of its possible astronomical alignments had ever been conducted. As Wendorf, Schild, and Malville wrote in 2008, “. . . a well-known stone circle was discovered by Bagnold (1931 [

sic

] in the Libyan Desert. . . . No evidence of astronomical orientations had been reported, and none is readily discernable in photographs of the

circle.”

32

Because of its incredible remoteness, few people have actually seen Bagnold Circle, let alone studied it in detail on location.

*32

As far as we know it was not visited until the 1990s, when four-wheel-drive vehicles became available in Egypt and the military authorities slackened their rules for tourists' deep desert travel. In a 1998 visit by Zarzoora Expeditions of the Egyptian Wael T. Abed, the group apparently placed a cairn (small pile of stones) in the center of the circle. In 2001â2002, the Fliegel Jezerniczky Expedition (FJE) also visited Bagnold Circle. Additionally, Mahmoud Marai brought small groups to Bagnold Circle a few times from 2004 to 2007. It was Marai who guided us to Bagnold Circle in April 2008. Yet neither the Zarzoora Expedition nor the FJE checked for any possible astronomical alignments at Bagnold Circleânor had anyone else, as far as we could tell.

*33

Â

33

Bagnold Circle lies in a shallow basin, probably an ancient seasonal lake similar to the one at Nabta Playa.

â 34

The physical features we noted first were two prominent, upright, and elongated stones (very reminiscent of the gate stones of the Calendar Circle at Nabta Playa) that defined an eastâwest alignment. One of these stones on the west side was white, and the stone on the eastern side was black, which may indicate a symbolic significance of some sort. For our GPS we took readings of this alignment as well as readings for the northâsouth alignment, which also had at each end a very dark-colored stone, nearly black, and a very light-colored stone, nearly white. The conditions of the stones suggest extreme age: they have been deeply scoured by millennia of wind erosion. Some of the stones have suffered such extreme erosion that their tops have fallen off and are still on the ground where they fell. Notwithstanding this erosion, the circle is remarkably well preserved, considering its vast age. The two alignmentsâeastâwest and northâsouthâstrongly imply an astronomical function for the Bagnold Circle.

Figure 4.15. Bagnold Circle northâsouth alignment

Another clue are twenty-eight stones that form the circumference of the circle, which is not only implicit of the lunar phase cycle of 29.5 days but, more important for us, also brought to our attention a clear connection to the Calendar Circle at Nabta Playa, which also had twenty-nine stones around its circumference. We also noted that north of the circle there was an elongated low hill that suggests observation of the low northern sky, possibly for marking the passage of a circumpolar constellation or star.

*35

One of the most nagging questions that constantly comes to mind in this totally desolate and extremely remote place of the Egyptian Sahara is this: Why build anything here at all? What could have influenced the ancient people who roamed the deep desert to go to the trouble of constructing a stone circle in the middle of nowhere and, furthermore, to align it to the four cardinal directions? The answer, ironically enough, may actually be that they did so because of the location itselfâor, to be more specific, of the latitude of the place. Today Bagnold Circle is approximately 23.5 degrees north and just a fraction north of the Tropic of Cancer.

â 36

Using the circle's precise latitude and checking the earth's ancient obliquity at various epochs, we found out that from 13,110 BCE to 1490 BCE, the circle was located just south of the Tropic of Cancer. This means that within that range of epochs the sun passed directly overhead exactly at the zenith a few days before and a few day after the summer solstice. This time of year was when the monsoon rains started drenching the desert and may be a reasonâthough perhaps not the only reasonâfor locating the stone circle here. We can recall from chapter 2 that in 1999 Carlo Bergmann discovered the Abu Ballas Trail, an ancient donkey trail that ran across the 500 kilometers (311 miles) of waterless desert between the Dakhla oasis and Gilf Kebir. Although anthropologists and Egyptologists have agreed that this trail was used by ancient Egyptians of the late Old Kingdom, Bergmann believes it was used as early as the Late Neolithic, about 5500â3400 BCE. Bagnold Circle is located a bit west of this trail, and it is quite possible that it served as a point for a shortcut route to Gilf Kebir, perhaps by the same Neolithic people who once populated Gilf Kebir and Jebel Uwainat.

We also found more evidence of prehistoric astronomy in the region when southwest of Bagnold Circle, 250 kilometers (155 miles) away in the wadi Karkur Talh region on the north of Jebel Uwainat at a latitude of 21.98 degrees north, we found an apparent solstice sunset marker. At a large rock face with western exposure, which contains glyphs of giraffes and human figures, there is an outcrop or mound on the cliff face about twelve feet high. Scrambling up the rock mound, we found on it a number of skillfully engraved marks, including an obvious arrow pointing toward the northwest horizon. Returning with our electronic compass we measured the arrow as pointing approximately 26 degrees north of west, for an azimuth of 296 degrees, which marks the sunset on the day of summer solstice. This type of skillfully engraved rather than painted art tends to be on the more ancient end of the spectrum of rock art in the region. Given that the rock face also contained images of giraffes, we estimate that this solstice marker may predate 6000 BCE. In addition, when we were en route from Bagnold's Circle to the Gilf Kebir region, traveling not far from the Libyan border, we came across a large, isolated standing stone that protruded more than 1 meter (3 feet) out of the ground. Located in the middle of a long, narrow, flat basin, or wadi, that was convenient for our jeeps to drive on because of its featureless flatness, this stone was smooth, cylindrically shaped, and standing only a few degrees off vertical. It appeared likely to have been placed by humans, possibly as a gnomon with both solar and phallic allusions.

Figure 4.16. Isolated standing stone north of Jebel Uwainat, oriented slightly off zenith and possibly a prehistoric gnomon.

Bagnold Circle gives all indications of being from the Neolithic epoch. It is probably a vestige left by traveling pastoralists whose temporary settlements dot the desert region that lead from the circle to Gilf Kebir and, in all likelihood, had their permanent abode in the wadis and plateaus of the Gilf Kebir and Jebel Uwainat mountains. The similarities of both the stones and the astronomical alignments of the Bagnold Circle and the Calendar Circle at Nabta Playa strongly suggest that we are dealing with the same Late Neolithic people whose images are present in the rock art of Gilf Kebir and, more prolifically, at Jebel Uwainat. Further, at Jebel Uwainat, the engraved arrow that we discovered and that quite plausibly was intended to mark the summer solstice sunset was probably associated with the same extended cultural group. More explorations are necessary to find the human remains of these astro-ceremonialists and navigators of the Egyptian Sahara, but these findings contribute another important aspect to our story of how their knowledge of astronomy, desert navigation, rudimentary agriculture, and domestication of cattle were important elements in the creation of the pharaonic state when, around 3400 BCE, the Sahara became super-arid and forced these mysterious desert dwellers to migrate eastward into the Nile Valley.

Figure 4.17. Elevated horizontal rock face at the northern edge of Jebel Uwainat, with engraved linear features and arrow pointing to the summer solstice sunset

So, with such thoughts in mind, we set out on what was a scorchingly hot and rugged drive to Gilf Kabir. We will pick up this story at the end of chapter 5. Meanwhile we ask: Who were these mysterious people that populated the Egyptian Sahara in such remote antiquity? How did they look? Can we refer to them as Egyptians? Perhaps most intriguing of all, where had they come from in the first place?