Bloody Passage (v5) (20 page)

Read Bloody Passage (v5) Online

Authors: Jack Higgins

Gatano moved to join them and stood on the other side of the chair holding a Sterling. Wyatt raised his head slowly and I saw the dreadful pain on his face, and realized beyond any doubt that he was holding on to the final threads of life with all his strength. And I saw something more--Nino appearing round a buttress, halfway up the wall beneath the far end of the terrace.

Stavrou said something to Wyatt, I don't know what, and Wyatt gave a sudden agonized cry and turned to glance at me over his shoulder. "I'm sorry, Grant, there isn't time."

His hand came out of the right-hand pocket of his reefer coat and he was holding a Sturma stick grenade. There was a moment of total stillness and then, as Stavrou tried to turn, dropping one of his canes, the grenade exploded with devastating effect, taking out Gatano as well.

Barzini had his revolver already in his hand, but it wasn't necessary, for Moro and Bonetti, stunned by what had happened, could only stand and stare at the butcher's shop the courtyard had become.

As for me, I ran for the steps, too late, for high on the terrace, Frau Kubel had turned and was running toward Hannah, gun in hand, and Nino was still just below the overhang.

And then a rather large miracle occurred, for as the old woman paused ten feet away from her target and took careful aim, the Doberman leapt for her throat. She screamed once and they went back together over the rail falling through space, passing from sight to the rocks below.

I kept on going, taking the steps two at a time and arrived on the terrace as Nino scrambled over the rail at the other end. Hannah turned toward me, a hand outstretched.

"Who is it? What's happening?"

"Hannah," I said. "It's me--Oliver."

A look of complete bewilderment appeared on her face and she moved forward, her hands reaching out to touch. And then she smiled.

"Oliver," she said. "What kept you?"

For the first time since childhood I felt like weeping, so intense was the emotion of the moment, but I contented myself with putting my arms around her and holding her as if I'd never let her go.

W

e left again in

Palmyra

within the hour and sailed into Palermo harbor at dawn the following day. I wanted Hannah away from there and back home without delay, so Barzini pulled strings and got us seats on the flight to London that same afternoon.

He took us out to the airport at Punta Raise himself in the yellow Alfa--me, Hannah, and Simone. Nino stayed home, the streets of Palermo still unsafe for him until his uncle had the chance to arrange matters. We had an emotional farewell.

"It was a great climb," I said.

"I know, like the English say, a piece of cake." And then he laughed. "Only in the end it turned out to be a bigger slice than I thought."

At the airport, Barzini and I left the girls talking and moved out on the terrace for a final word. "Well, it was very interesting," he said.

"You can say that again. What do you think the authorities will make of it?"

"Simple enough. With an explosion like that, I'd say they'll assume some of Stavrou's old Mafia pals caught up with him."

"And Moro and Bonetti?"

"They'll button up. No percentage for them in shooting their mouths off." He lit one of his vile Egyptian cheroots. "Yes, it was quite like old times."

"Only we're not as young as we were."

"So you feel that way, too?" He grinned. "Time to settle down, Oliver, with a good woman." He looked inside at Hannah and Simone. "Are you likely to be coming back this way?"

"I don't think so. Not for a while anyway. I need a rest."

"A pity. Still, I'll send her in to you."

He went back to the two girls and after a moment or so of conversation, Simone came out on the terrace.

"Well?" she said.

"Are you all right for money?"

"I have a bank account here. Enough for now. And Aldo's offered me a job, if I want one, doing the stage design at that beach club of his."

"That's nice."

I lit a cigarette. She said, "What will you do? Afterward, I mean?"

"God knows."

She reached out suddenly and touched my hand. "I'm sorry, Oliver."

"What for?"

"You know what I mean. The way things were at the beginning."

"Never apologize for anything," I said. "It's a sign of weakness."

"Damn you!" she said, and then they called our flight over the tannoy and that was very much that.

As for Hannah, I decided to tell her the truth for once in my life, in every detail, and tossed in a few unpleasant facts about her brother while I was at it.

She took it extremely well under the circumstances, which is more than I can say for my grandmother, who received me coldly in the beautiful Victorian drawing room of her house in St. John's Wood and demanded an accounting.

When I was finished she said, "I don't think you should come here again, Oliver. Not for a while at any rate."

"I know," I said. "I'm bad news."

"Bad for Hannah," she replied calmly. "And that is all that concerns me."

Which was fair enough. I stayed in London another two days, mainly to see my lawyer and make certain financial arrangements, then I caught a flight to Madrid where I hired a car and drove south.

It was late afternoon when I arrived at the villa at Cape de Gata. Everything was exactly the same as I had left it on that day a thousand years ago when it had all started--except for one thing. The Alfa was parked in the courtyard.

I had a quick look round the villa, but there was no one there, so I got back into the hired car and drove down toward the marshes.

I found her at the end of the causeway, sitting in front of her easel, painting. When I got out of the car she made no sign. It was, of course, a watercolor as usual, a view of the marsh and the sea and the evening sky beyond, that was very fine indeed.

I said, "You get better all the time. That background wash is fantastic."

She said, "It occurred to me that you wouldn't know where I'd left the Alfa. I thought I'd better return it."

"Thanks," I said.

I lit a cigarette and crouched down beside her. The sea was calm, the evening sky the color of brass. A sandpiper skimmed the water and fled like a departing spirit. It was all very peaceful. I wondered for how long.

Jack Higgins is the pseudonym of Harry Patterson (b. 1929), the

New York Times

bestselling author of more than seventy thrillers, including

The Eagle Has Landed

and

The Wolf at the Door

. His books have sold more than 250 million copies worldwide.

Born in Newcastle upon Tyne, England, Patterson grew up in Belfast, Northern Ireland. As a child, Patterson was a voracious reader and later credited his passion for reading with fueling his creative drive to be an author. His upbringing in Belfast also exposed him to the political and religious violence that characterized the city at the time. At seven years old, Patterson was caught in gunfire while riding a tram, and later was in a Belfast movie theater when it was bombed. Though he escaped from both attacks unharmed, the turmoil in Northern Ireland would later become a significant influence in his books, many of which prominently feature the Irish Republican Army. After attending grammar school and college in Leeds, England, Patterson joined the British Army and served two years in the Household Cavalry, from 1947 to 1949, stationed along the East German border. He was considered an expert sharpshooter.

Following his military service, Patterson earned a degree in sociology from the London School of Economics, which led to teaching jobs at two English colleges. In 1959, while teaching at James Graham College, Patterson began writing novels, including some under the alias James Graham. As his popularity grew, Patterson left teaching to write full time. With the 1975 publication of the international blockbuster

The Eagle Has Landed

, which was later made into a movie of the same name starring Michael Caine, Patterson became a regular fixture on bestseller lists. His books draw heavily from history and include prominent figures--such as John Dillinger--and often center around significant events from such conflicts as World War II, the Korean War, and the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Patterson lives in Jersey, in the Channel Islands.

Patterson as an infant with his mother, grandmother, and great grandmother. He moved to Northern Ireland with his family as a child, staying there until he was twelve years old.

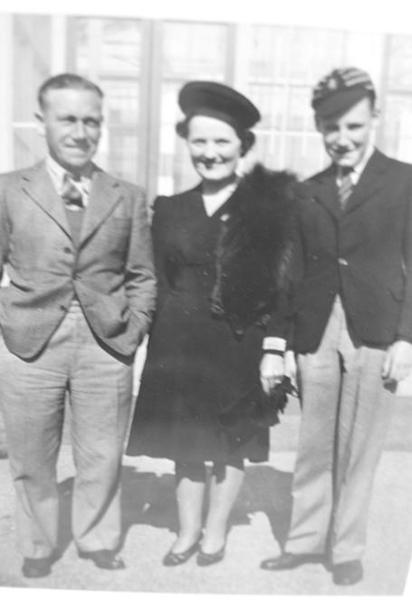

Patterson with his parents. He left school at age fifteen, finding his place instead in the British military.

A candid photo of Patterson during his military years. While enlisted in the army, he was known for his higher-than-average military IQ. Many of Patterson's books would later incorporate elements of the military experience.

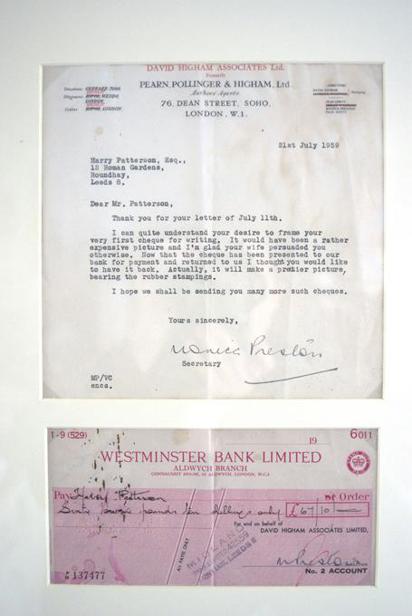

Patterson's first payment as an author, a check for PS67. Though he wanted to frame the check rather than cash it, he was persuaded otherwise by his wife. The bank returned the check after payment, writing that, "It will make a prettier picture, bearing the rubber stampings."