Blue Angel (21 page)

Authors: Donald Spoto

That week she recorded German melodies in a Paris studio and began a week’s work dubbing the French version of

Song of Songs;

then she, Maria, Rudi and Tamara toured France, Switzerland, Austria, Italy and the Riviera. But it was Paris most of all that she thenceforth regarded as a refuge. “I am very happy here,” she told the press. “My daughter can play in the gardens of the hotel or in the park without fear [of publicity or abduction].”

On September 26, she and Maria left Paris for New York, her garb and makeup as controversial as ever—a black and silver suit over a Chinese red blouse, matching red and black gloves and snakeskin bag, red heels on black patent pumps and her lips and fingernails painted a blazing scarlet. Hours before her departure, she was visited by German film distributors authorized to solicit her to return home to make films. But Dietrich condemned to their faces the recent dismissal from Germany of prominent intellectuals (most of them Jewish) and expressed her outrage at the May book-burnings on the Opernplatz, in which the works of Heine, Marx, Freud, Mann, Brecht and Remarque were especially targeted. Contemptuous not only of her own recent press but also of everything that the Nazis stood for, she coldly rejected their offer—as she did at least two later invitations before she sealed her loyalties by swearing American citizenship.

*

W

HEN

M

ARLENE

D

IETRICH RETURNED TO THE

States in the autumn of 1933, she was (although not a refugee) one

of almost two hundred thousand Germans who settled in the United States in that decade.

*

Quite apart from their fierce rejection of Nazi ideology there was a subtle but well-documented self-loathing among many of these immigrants. Once champions of German culture—as Dietrich often referred to herself from 1930 to 1933—they now almost denounced their roots. Bertolt Brecht, who also settled in California, proclaimed that “everything bad in me” was of German origin, and Thomas Mann, speaking for many, lamented, “We poor Germans! We are fundamentally lonely, even when we are famous! No one really likes us.”

Marlene Dietrich could not say with any truth that she was disliked. By the same token, she seemed to exhibit the common schizoid pattern of the German émigré, rejecting her Teutonic past and refusing to conform entirely to American behavior, particularly with regard to gender roles. Simultaneously, she loved the California climate as much as her huge salary and the freedom to enjoy it—yet she complained about almost everything, and almost constantly. Hollywood was impressive in its technical efficiency; Hollywood was dreadful, and she never felt at home there. She appreciated her many American friends; she decried the informality of their lives. She enjoyed the abundance and variety of food and the opulence of restaurants; she criticized American cuisine and said she preferred to cook German-style at home. She disliked the social arrogance of many Germans in Hollywood; she dined at least once weekly at the Blue Danube restaurant, where old friends like Joe May kept the Old World alive in High German conversations. Of such contradictions was the immigrant temperament comprised before 1941—by which time American citizenship had bonded most of them forever to their adopted countrymen, whom they fervently joined against Hitler.

In October, Dietrich was back at Paramount with von Sternberg, then completing the scenario for what would be one of the

most curious movies in history. First called

Her Regiment of Lovers

, this was a wildly imaginative account of Sophia Frederica, the Prussian princess brought to Russia in the eighteenth century by the Empress Elizabeth to marry her halfwit son Peter. Learning every political and sexual tactic of ambition and exploitation at the Russian court, Sophia—renamed Catherine (and later “the Great”)—accedes to the throne after the death of Elizabeth and the murder of Peter. Soon retitled

The Scarlet Empress

, the design of the production proceeded under von Sternberg’s complete control—each tiny detail of scenery, paintings, sculptures, costumes, story, photography and acting gesture. The film became, as he said, a relentless excursion into style. The credits claim the story is based on the diary of Catherine II, “arranged by Manuel Komroff”; in fact it emerged whole from von Sternberg’s most ardent inventiveness.

No matter that the narrative only vaguely nods at historical accuracy, the director’s goal was a presentation of something unique in the annals of film: the twisted world of nightmare, a tissue of almost pathological fantasies. Inspired by German expressionism and its use of distorted perspective to suggest mental derangement,

The Scarlet Empress

and its lacerating, perverse wit totter so often on the edge of satire that the appropriate response to almost every scene is problematical. Hyperbolic in design, the sets and props impede the players, Dietrich herself included (not to say the thousands of extras employed for crowd scenes), and von Sternberg’s vision emphasized an astonishing collection of brooding, expressionist statues and vast ikons that everywhere dwarf the characters. Equally grotesque were explicit scenes of torture, rape and pillage (production just preceded the application of the newly drafted Motion Picture Production Code that set standards for acceptable language and behavior for the first time in Hollywood’s history).

This florid production featured everything beyond human scale, from the vast oversize palace corridors to doorhandles twelve feet off the ground, requiring half a dozen characters to manipulate them. Amid a delirium that could have come from Edvard Munch, Dietrich as Catherine was swathed in ermine, white fox and sable, wrapped in fog and smoke, a creature looming from a demented social miasma and finally transformed into a half-mad sybarite. For the first half of the film, she had little to do but affect a wide-eyed naïveté; then, as the images of sadomasochism accumulate, she was presented as a woman whose unleashed sensuality makes her a monster of ambition (“I think I have weapons that are far more powerful than any political machine”). Amid a swirl of gargoyles with twisted bodies and images of emaciated martyrs bearing vast candelabra, no exoticism was left untried, and the picture became a procession of mobile tableaux.

As Amy Jolly in

Morocco

, 1930, with von Sternberg’s radiant key lighting.

At the premiere of

Morocco

, with friend Dimitri Buchowetzki and Rudolf Sieber.

Exploiting a photo opportunity with Charles Chaplin in Berlin, 1931.

Filming

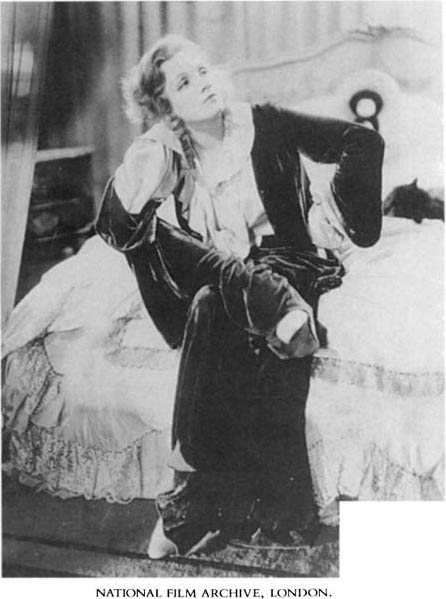

Dishonored

in 1931: an obvious rival to Garbo.

Posing on the set in 1931 as Shanghai Lily in

Shanghai Express

, wearing one of Travis Banton’s fantastic creations.

With her daughter, Maria, in Hollywood, 1932.

With actresses Suzy Vernon and Imperio Argentina at a Ladies’ Night in Hollywood, 1932.