Born to Be Brad (6 page)

Authors: Brad Goreski

For me, high school was a study in isolation. I was fifteen years old, sitting on my windowsill, beneath the same gold sequined Roman shades my mother made for me. My bedroom was my refuge. I was lighting incense and candles and staring up at the stars, smoking a cigarette out the window, dreaming of a better place. It was high drama! But I lived in fear of going to school. I was superstitious bordering on obsessive-compulsive. I said a prayer in the morning and another at night, asking Him (whoever He is) to watch over me. If I fell asleep before saying the prayer, I was convinced the next day would be tragic.

“For me, high school was a study in isolation.”

And let’s face it: Sometimes it was. High school is tough, the hallways often cold. A teenager’s locker is one of their few chances for self-expression, and I wanted to personalize mine with photos of Calvin Klein models. But I didn’t want to draw any more attention to myself. So I hung photos of the Beastie Boys instead—still personal, because I loved their wit, but less conspicuous. Sometimes I ate lunch in the stairwell with two girlfriends, usually salad I brought with me from home. Or I ate in the school library, even though we weren’t supposed to. The teachers didn’t have the heart to tell me to go to the cafeteria, because they knew I could no longer walk into the cafeteria without the boys in my class throwing food at me. I can’t remember a single day where someone didn’t imitate my voice in class. Or call me the F-word in the hallways. The word did hurt, but not because it was a surprise to me. Duh! I knew I was gay the first time I saw the opening credits to

Who’s the Boss

and a shirtless Tony Danza opened the shower curtain. The word hurt because it made it all real. It meant I would have to act on those feelings one day soon. And I was scared by what that meant for my life. I didn’t have any role models; I didn’t have a picture of what a happy, well-adjusted gay couple would look like. I thought being gay meant angry families and loneliness. I was worried about the loneliness. High school—for me and every other teenager since the dawn of time—was a minefield of angst like

My So-Called Life,

except in real life Jared Leto never falls in love with the girl with the Kool-Aid dye job.

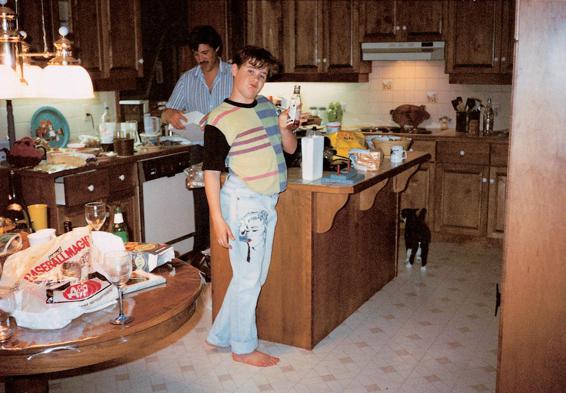

This photograph is all about the jeans. I spotted them at a store called Northern Reflections. And they were expensive—because some crazy queen hand-painted Madonna’s face on the right thigh. I begged my mom to buy these for me, which she did. And I wore them everywhere.

“I didn’t have any role models; I didn’t have a picture of what a happy, well-adjusted gay couple would look like.”

I made an effort. I should say this. For exactly two weeks I tried to fit in. I tried to pare it down, to limit the color in every sense. But it didn’t feel right. It didn’t feel like

me.

Besides, people knew who I was. People knew what I was. I was the kid who plucked his eyebrows so much that there was basically one hair left. One tiny little hair. I was only fooling myself. I cried a lot—often because my sister was gone, off to university. She and I had talked about my sexuality before she left. I told her I thought I was gay. Of course I knew I was gay, but I was trying to test the waters, to see what her reaction might be. Any time I got up the courage to float the idea, her answer was always the same: “You’ll be what you’re gonna be. And you’re my brother. It doesn’t matter.”

If I had an escape in these years—beyond my bedroom windowsill and the basement with the sewing machine and my pictures of Claudia Schiffer and Naomi Campbell—if there was a place where I could be myself, unapologetically, it was theater camp. The summer after tenth grade, I enrolled in a one-week intensive drama program called Theater Ontario. I know that seven days doesn’t sound like much time, but the experience was transformative. It wasn’t just the classes, though the instruction was impressive, too. I took stage combat lessons and musical theater workshops and worked on monologues and learned to tap dance. But what made more of an impression was the taste of freedom. We kids lived in college dorms and stayed up all night dancing. Not sleeping was a point of pride. We chanted like Buddhists in the courtyard for hours. There was a real hippie vibe to the place and we embraced the free-love spirit. It was a chance for self-expression. There was the gamine girl with the red pixie haircut who wore baby-doll dresses with denim shorts underneath—a heightened nineties look. There was the girl who wore a tailcoat every single day. And the girl who sat in the courtyard with a broken keyboard, playing original songs with gibberish lyrics, and we’d all listen and do interpretive dance. It was all about feeling the moment. That summer I kissed a boy for the first time. His name was Ian, and I knew enough to know I liked it, that it felt right to me. Girls were my friends, not my love interests.

“It’s like

Footloose,

minus the hot Southern boys and the angsty solo dance scene.”

This collection of outsiders at Theater Ontario? The ones who came from local communities that weren’t always accepting of them? We were thrilled to have found one another. And so we kept the camp spirit alive during the winter by getting together as often as possible. My friend Victoria—with the big eyes and the chestnut, shoulder-length hair—would come visit me in Port Perry; we’d walk the town’s Main Street and she’d laugh. “Why does every store sell potpourri!” she’d say. I couldn’t argue with her; she was right. There wasn’t much to do in Port Perry, I said. This was the kind of place where teenagers take their pickup trucks out to the cornfield and drink cans of beer in front of a bonfire. It’s like

Footloose,

minus the hot Southern boys and the angsty solo dance scene. And so Victoria and I would sit in the Goreski family hot tub in our backyard, pretending we were mermaids. We were bored. We painted our nails black. We ate too much. We called ourselves Fat Brad and Fat Victoria, and we got excited about putting potato chips in our sandwiches. I tried to dye Victoria’s hair blond, which high school kids everywhere need to stop doing, by the way. It was a disaster. She’d previously put henna in her hair to give it a reddish tint, and when I applied the bleach the chemicals burned her scalp and ruined the color.

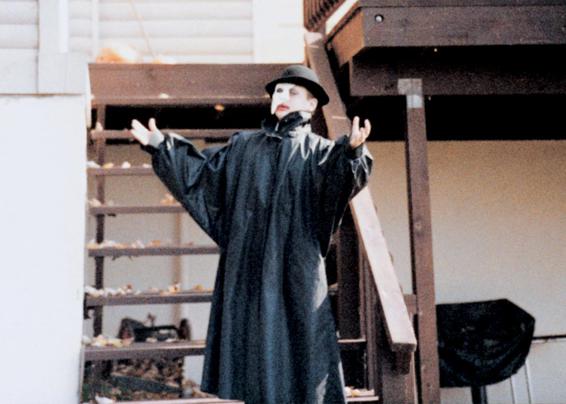

Halloween 1994. I was obsessed with

The Phantom of the Opera

. When it was announced that the musical was coming to Toronto, my grandfather got on the phone immediately and bought tickets for the family.

Reduce, Reuse, Recycle

HOW TO BUY VINTAGE (AND WHEN TO WALK AWAY!)

1. Don’t be afraid to get dirty. Sometimes you have to dig deep to find that one precious item. Roll up your sleeves, grab some Purell, and get in there.

2. Know what you are shopping for. Vintage shops and flea markets can be overwhelming. But if you have a direction, you’re more likely to find what you’re looking for—and maybe, if you’re lucky, you’ll find some hidden treasures along the way.

3. Point and click. I buy a lot of vintage online at eBay and 1stdibs to give as gifts—especially jewelry. There are some great resources and great deals and you don’t have to leave the comfort of your own home. It’s always nice to avoid that extra price markup you often find in stores.

4. Do your homework. When you travel, look for local flea markets and ask about the great vintage stores. Each country/city has its own unique pieces, and your purchases will be mementos of your adventures.

5. If the price is right but the item is too big, it’s often worth it to make the purchase and then have it altered. Don’t leave behind a good find just because it is too big. You may regret it later …

6. Let yourself

splurge

on that designer item you’re lusting over. I almost left a Chanel briefcase behind in a vintage store in Paris and found myself running back hours later, minutes before closing time. It’s one of my fave items I own!

It was more fun when I went into Toronto on the weekends, taking the train to Victoria’s apartment, where our camp friends would all descend. Victoria was raised by a single mom, a progressive hippie who didn’t much care what we did, and she never asked questions. Friends would come in for auditions and crash at Victoria’s two-bedroom. You never had to give much notice. You’d call on a Friday night and say, “I’m getting on the train. I’ll be at Union Station at ten. OK?” And it was. It was a lot of slumber parties and all-ages rock shows and tickets to Lollapalooza. We’d go to the theater. We’d go shopping on Queen Street, stopping into Black Market for vintage T-shirts and going to the Goodwill store, where you could buy clothes and pay by the pound. Looking back on it, buying used clothing in bulk sounds pretty gross. But for a teenager with no money, there was nothing better than walking out of a store with a couple pounds of new clothing. It made us feel rich. It was a beautiful time capsule. Best of all, at Victoria’s apartment, it wasn’t just that I could be gay. I could

talk

about it. Out loud. Victoria was “of the city.” She was one of the first people I met where I thought, I don’t need to have any secrets with you.

This was the nineties. Kurt Cobain had passed away and I’d gotten into the grunge scene. I was often angry in these years. Unable to channel my frustrations into words, I expressed myself through fashion, just like I had as an eleven-year-old pretending to be Don Johnson at my communion. I started listening to the Breeders and Nine Inch Nails and Smashing Pumpkins and I stopped wearing penny loafers. I fell under the spell of the Seattle movement, and I wasn’t alone. In 1992 I remember watching Marc Jacobs on

Fashion Television

talking about the grunge collection he designed for Perry Ellis—the daring line that got him fired from the venerable label. Steven Meisel photographed that flannel collection for

Vogue

in a legendary shoot with Naomi Campbell, Nadja Auermann, and Kristen McMenamy. I tore those pages out of the magazine, savoring the images of Kristen with that pageboy haircut and the beat-up purple Doc Martens and the leather jacket and flannel shirt tied around her waist. It was the antithesis of everything I’d worn before and I loved it. I kept these magazine clippings in a file (which my dad still has). I kept all of the Guess ads, because I was obsessed with Claudia Schiffer—another sort of neo–Marilyn Monroe. I grew my hair long, dyed it auburn and then jet-black.

“I was often angry in these years. Unable to channel my frustrations into words, I expressed myself through fashion.”

Grunge fashion was my armor. I was Ally Sheedy on the outside but Molly Ringwald on the inside. We were listening to Hole and angry Seattle noise. And we were experimenting with alcohol, and later with marijuana. We were leaving Victoria’s apartment after midnight and not coming home until the sun came up. We were part-time club kids, too, plain and simple, and to me it was all very glamorous. We’d board a bus that would take us to a secret location. It was always some secret location and we’d end up God knows where in a warehouse and dancing all night with pacifiers and whistles and candy necklaces around our necks.

“Grunge fashion was my armor. I was Ally Sheedy on the outside but Molly Ringwald on the inside.”

For me, rave culture was all about the clothing. It was a chance to dress up and play a character—in the same way I did at Halloween. At vintage stores, I drew my inspiration not just from

Vogue

but also from a

Geraldo

episode on New York club kids. I wore knee-high socks and terry-cloth shorts and skintight T-shirts and a see-through Pocahontas knapsack. At Victoria’s apartment, I could play dress-up all the time. I could listen to gay house music we bought on cassette and put on a sailor costume and sequins and let Victoria paint fake tattoos on my arms. When I’d been into grunge, my hair was long and always a different color. Now I chopped it all off. Victoria and I would buy Bingo Dabber—it was almost like puffy paint, the kind bingo players used to ink up their cards. But we put it in our hair. We’d squeeze the tube against our heads, and it would look like we had full pink plastic helmets on. It was major. I’d come home on Sundays covered in glitter and sleep straight through until Monday morning.