Bracelet of Bones (11 page)

“It does,” said Solveig. “To him it does.”

“Makers like nothing more than to talk about their work,” observed Bruni. “It’s what’s most alive for them.”

“Mmm!” agreed Solveig, smiling. “I can’t explain it exactly. But for me, well, meeting him was like taking a step onto the rainbow bridge.”

“Heh?” inquired Vigot.

“That little workshop. It’s like the bridge between middle-earth and Asgard. Between humans and gods. For me it is.”

“You mean,” said Bruni, “that when men make something fine . . .”

“Yes,” said Solveig. “Somehow, the gods strike a spark in them.”

“With strike-a-lights!” said Vigot.

“No, you don’t understand.”

“There’s a story,” Bruni told them, “about how Odin won the goblet brimming with the mead of poetry. He shared it out between all the gods, but now and then he offers a drop or two to some human.”

“That’s what I mean,” said Solveig eagerly. “It’s like that.”

“He didn’t ask us anything about our journey,” Vigot said. “The crew . . . the cargo . . . where we’re going.”

“He asked you what kind of fish you want to catch,” Solveig reminded him.

“All kinds,” Vigot replied, and he flashed her a handsome smile. “Big ones, small ones, they can’t escape me.”

Bruni grunted. “Thinking about girls again, are you, Vigot?”

“And fish,” said Vigot.

“You’ve got a mind like a cesspit.”

“And you’re my teacher,” Vigot retorted.

Bruni gave Vigot a scornful look, and his thick lips parted. “So says the pot,” he sneered. Then he glanced at Solveig. “Ignore him,” he told her. “Vigot and his fish, they’ve reminded me of something.”

“What?” asked Solveig.

“Hooked, are you?” said Bruni, and his mouth fell open again. “Listen to this! Thor went out fishing, and do you know what he used for bait?”

“A turd,” said Vigot.

“No,” said Bruni. “He baited his hook—his very big hook, Vigot—with the head of an ox.

“In the depths of the sea the monster was waiting, the Midgard Serpent coiled around our middle-earth. He let go of his tail and snapped at the bait, and the sea frothed like ale. It fizzed. But Thor hauled up the monster. Then he reached for his hammer and whacked the serpent’s head. The Midgard Serpent tugged, and the huge barb tore at the roof of his mouth. He jerked his head from side to side, he wrenched . . .”

Bruni grunted, he spluttered and spit like the Midgard Serpent—and he woke all the sleeping dogs of Ladoga.

No more than a couple of hundred paces from their boat, Solveig and Vigot could hear yowling and yapping, and it was coming closer.

“You and your monster!” snapped Vigot. “You’ve woken them all up.”

Then two huge hounds came bounding along the quay toward them, snarling.

Bruni stood his ground and roared at them. But that only maddened the dogs all the more. They mobbed the three companions. Solveig could hear them panting and smell their foul hot breath.

“Clear off!” yelled Vigot, picking up a paddle lying beside the Bulgars’ boat.

But even as he did so, one of the hounds snarled and jumped at Solveig, knocking her off balance.

“Run for it!” yelled Bruni.

But Solveig couldn’t do anything of the kind. She stumbled backward, she clawed the air, and then both hounds leaped at her. She could see their gleaming eyes. Their pointed teeth.

Solveig shrieked. She tried to fight them off.

But one hound bit deep into her left calf, and the other sank his teeth right into her slender neck.

Solveig screamed. She screamed as never in her life before. And then she heard a massive clout—a thwack!—and felt the heavy body of one hound collapsing on her.

“Got you!” shouted Vigot. “You hellhound! Now you!”

The other dog didn’t give him a chance. Seeing the dreadful fate that had befallen his companion, he ran off with his tail between his legs, howling.

Vigot turned back to the first hound. He gave him a poke with the paddle and then whacked his head again. The hound slathered strings of spittle and blood all over Solveig’s back and shoulders.

“Get him off!” spluttered Bruni. “Come on!”

So both men dragged the heavy hound off Solveig’s body, and then Bruni knelt beside her.

“Girl!” he said. “Solveig! You’re safe.”

Solveig was curled up as if she were unborn. Her bandaged left hand was clamped to her neck. With her other, she clutched her bleeding calf. Her whole body was shaking. And when she heard Bruni reassuring her, she began to sob.

Bruni put his hands under Solveig’s shoulders and tried to help her to her feet, but she had no strength in her calves and thighs. No kick in her limbs, no force in her body except for her palpitating heart. So when Bruni relaxed his grip, she just slumped down on the quay again.

“Come on, girl,” Bruni encouraged her.

But Solveig lay in a heap, shaking and sobbing.

Bruni sniffed and scratched his right ear. “Nasty!” he said.

“Hellhounds,” said Vigot. “Killers.”

Bruni stared at him. “Like you,” he said thoughtfully.

“A good thing too,” Vigot replied. And then, more fiercely, “Isn’t it?”

Bruni got down on his knees beside Solveig. “I’ll carry you back, girl,” he said.

“I’ll carry her,” said Vigot.

But Bruni slipped his arms under Solveig’s back and hips and looked up at Vigot with a challenging smile.

Still Solveig couldn’t stop sobbing. Bruni was rocking her in his arms, like a baby almost, and she felt utterly unable. She wished only that she’d never left home. With all her head and heart and torn body, she wished she had never come.

11

S

olveig’s blood raged around her body. At one moment she sat up, not knowing where she was, and reached out, gabbling gibberish no one could understand. At another she lay back, soaked in her own sweat, gasping for breath. She screamed; then she lay so silent that her companions thought words had left her forever; she trembled and moaned.

Odindisa nursed Solveig all night. She laid her head across her lap, she said and sang spells over her and rubbed honey into her wounds; she pounded thyme and mint and other herbs and mixed them with a yolk and fed them to Solveig, fingertip by fingertip.

“As long as the bites don’t blacken,” she told everyone. “As long as her wounds still hurt her . . .”

At times, Solveig half heard voices around her.

“Wrong. We were wrong. We should never have brought her.”

“The Norns are against her.”

“Scarcely a day’s carving.”

“Sell her!”

“A fool’s errand! . . . No more chance than a frog flying to the moon.”

But although Solveig could hear snatches and knew they were talking about her, she was unable to reply.

In the middle of the night, Solveig had a waking dream. She was a tiny girl again, no more than two or three, and so terrified that her limbs locked and she was unable to move.

She could see her grandmother Amma standing over her and hear her frosty voice.

“I’ve told you before, Halfdan. Her eyes aren’t right, and she’s a weakling. You should have done it right away.”

Solveig’s father sat hunched over a bench, still as a stone.

“You should have left her out on the ice,” Amma went on. “Food for the wolves. We did that in the old days. It’s cruel, I know that, but the weakest in the litter can bring down the whole pack.”

“Enough!” Halfdan growled.

“Especially when there’s scarcely enough food to go around. A slip of a daughter. The last thing you need now that you’re on your own.”

Solveig’s father stood up, and in doing so he knocked over the bench. “I made my choice,” he said, “and I’d choose the same again.”

“She’s a death bringer,” Amma said bitterly. “She’s already killed her mother. Sun-strength! She’s a weakling and she . . .”

“No,” interrupted Halfdan. “Solveig is my blood and I’m hers. I did as I promised Siri, and she would curse you for what you’ve said.”

“I warned you, Halfdan,” Amma said, and she clenched her bony fist. “I warned you Sirith would die in childbirth. You mark my words, the day will come when Solveig’s weakness will harm others—maybe her own father.”

“Enough!” said Halfdan again. Then he scooped up his little daughter, and in her waking dream, Solveig could feel him holding her tight, very tight.

When Solveig opened her eyes, soon after dawn, this dream was still with her, bleak and painful. But she was still being held.

Then she saw Odindisa gazing down at her and realized she was lying in Odindisa’s lap.

“You’ve come back,” said Odindisa, smiling gently.

But Solveig couldn’t escape the night voices she had heard all around her. “What will he do with me?” she whispered.

“Who?”

“Red Ottar. He won’t sell me . . .”

“Never!” said Odindisa dismissively. “Over my dead body. I tell you, if you weren’t so strong, your bites would have done for you! You’d have died in the night.”

Strong? That was the last thing Solveig felt. She felt weak and frail.

“You’ve . . . mothered me,” she whispered.

“Now then. Did you talk to Oleg?”

Solveig sighed. She felt too tired to reply. She closed her eyes.

“I thought you would,” said Odindisa. “And you found the brooch.”

“It’s so beautiful,” Solveig whispered. “I told Oleg you’d come for it.”

Odindisa clicked her tongue. “Red Ottar’s changed his mind.”

Solveig opened her eyes again. They felt so heavy-lidded.

“I’ll buy it all the same, with Slothi’s hack-silver. I’ll buy it and tell Red Ottar later.”

“But . . .”

“He’s always changing his mind. Like a weather vane. To begin with he’ll be angry, but then he’ll be pleased . . .”

“How well you know him,” Solveig murmured.

Odindisa didn’t reply. She just narrowed her eyes and gave Solveig a sly look.

Then Solveig remembered the glass bead Oleg had given to her. Did I drop it on the quay? she wondered. Did Bruni or Vigot pick it up?

While Solveig was still wondering, Vigot appeared—as if by thinking of him she had somehow summoned him. He looked down at her, sharp-eyed.

“You again!” said Odindisa. “Vigot has been our regular night visitor.”

Solveig gazed up at him and gave him a smile as pale as the first aconite. “You saved me,” she said. “You saved my life.”

“What did you think I’d do? Stand and watch?”

“Shhh!” said Solveig gently, and her eyes filled with tears. “I’m thanking you.”

Vigot twisted his long fingers. Then he rubbed his right cheek where his wrestling opponent had gouged it.

“Still sore?” Solveig asked him.

“Not as sore as you.”

Solveig wondered whether to ask Vigot about the violet-gray bead, but she didn’t want him to think she was accusing him, so she decided to ask Bruni first.

Solveig’s next visitor was Red Ottar.

“If she weren’t so strong,” Odindisa told him, “the neck bite would have finished her.”

“Strong, is she?” said Red Ottar, staring at Solveig. “First your hand . . . Now this.”

Red Ottar could see Solveig was trembling, but that didn’t stop him.

“A treasure! That’s what Turpin called you. A bagful of bad luck—that’s what I say.”

Somewhere within her, Solveig rebelled. She refused to allow Red Ottar to wound her further.

“The gods are against you.”

“No!” she said huskily, and she screwed up her eyes. “If they were, I wouldn’t be here now.”

“I’m giving you one more chance,” the skipper told her. He shook his red head and then jammed his right thumb against the tip of her nose. “Anyhow, you’re needed on the quay. As soon as you can.”

“She’s not well enough today,” said Odindisa.

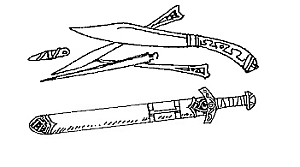

“Today’s the day to display our weapons,” Red Ottar told them. “Those fine scramasaxes! And that sword with the runes, the one Bruni made last winter.”

“I haven’t seen that yet,” Solveig said in a weak voice.

“You won’t forget it. It cuts itself into your skull.”

Solveig blinked. “I’ve got enough wounds already,” she said.

“And then tomorrow,” the skipper went on, “we’ll put out the carvings.” He glared at Solveig. “Such as they are. The weapons, the carvings, yes, and we’ve got to find a river pilot. Three men are coming aboard this afternoon.”

“Three?” said Odindisa.

“So we can choose the best. Everyone can have their say—for or against.”

Solveig hoisted herself onto her elbows. She was bright-eyed, flushed.

“Lie down, girl,” Red Ottar told her. “You’re feverish.”

Red Ottar soon dismissed the first pilot to come aboard. He sported a long, wispy fair mustache and had an annoying way of nodding the whole time while Red Ottar put questions to him—questions he slowly repeated before getting under way with his long-winded answers.

“Now you’re asking me how many days from Novgorod to Smolensk,” repeated the man. “Aren’t you asking me that?”

“I am!” barked the skipper. “I’m asking you, not the other way around. Have I got to wait until the Volkhov freezes over?”

“Until the Volkhov freezes over? Is that what you’re asking?”

“Get out!” Red Ottar said. “Torsten, ask him to ask you if he knows his way to the gangplank!”

The second pilot looked as mushy as a bag of slops. In fact, he even had some difficulty sitting down, and he sounded out of breath the whole time.

“Like your food, do you?” Red Ottar inquired.

“I do,” said the man with a squashy smile.

“So I see. You’ve piloted boats all the way to Kiev?”

“Mustn’t tell a lie,” the man replied. “That’s what my mother always said.”

“Well, have you or haven’t you?” demanded Red Ottar.

“Yes,” said the man, and he gave a high-pitched giggle. “Yes, I have! If I’d said no, I’d have been telling a lie.”

Bard brayed with laughter, and that made Brita laugh as well, but all the companions eyed each other and knitted their brows.

“Got you!” the fat man gurgled.

“Giggle, gaggle . . . gurgle!” Red Ottar exclaimed, waving his right hand. “Take him away.”

While the crew was waiting for the third pilot to come aboard, Solveig stood up and leaned against a gunwale. She still felt as unsteady as an old woman, and her neck was so swollen she couldn’t turn her head to left or right. But it was the last day of April, the air was soft, and she could hear the shorebirds calling.

Then she became aware that someone was standing beside her.

“Your neck,” said Brita. “It looks like boiled reindeer sausage.”

Solveig blinked.

Brita took Solveig’s arm and studied her neck very carefully. “Can I touch it?” she asked her.

But Solveig was saved from Brita’s scrutiny by Bard, who came hopping across the deck. “Hey!” he exclaimed, grabbing his sister’s hand. “Come and watch Torsten.”

The helmsman had a length of rope between his hands, and before long Solveig heard him saying, “What about a Turk’s head, then?”

“A Turk’s head?” Bard repeated. “A Turk’s head, is that what you said?”

“You’re as bad as that first pilot,” Torsten told him.

Brita bared her teeth. “What is it?” she asked, as if she wasn’t sure she really wanted to know. “A Turk’s head.”

“A stopper knot at the end of a rope. I’ll show you.”

“What’s it for?” asked Bard. “Oh! I know. When you’ve threaded the rope through an eye.”

“A ring, you mean,” said Brita.

“A ring is an eye,” Bard told her.

“Why’s it called a Turk’s head?” asked Brita.

Twice the helmsman twisted the end of the rope back around itself. Then he tucked in the end and held it up, but Brita was still none the wiser.

“It looks like a Turk’s headdress,” Torsten told her. “You’ll see.”

“What is a Turk, anyhow?” Brita asked.

But then, from behind her, Solveig heard Slothi saying very loudly, “No! Certainly not. It’s too risky.”

“He’ll change his mind. He always does.”

“No, Odindisa.”

“You . . . mean-minded Christian!”

They’re talking about buying Oleg’s brooch, thought Solveig. They must be.

“Slothi!” Vigot called out. “Slothi! Come and have a look at this!”

“Gladly!” said Slothi. He stood up and walked over to the far gunwale, where Vigot had hauled in one of his lines.

“Yuck! What’s that?”

Such was the force of Slothi’s exclamation that almost everyone turned to see what was going on.

Dangling from one of Vigot’s new bronze hooks was the most enormous shellfish. Not a cockle or mussel, crab or giant clam, but a creature covered in mud with a hairy shell and malevolent eyes.

“Let me see!” demanded Bard.

“Me,” said Brita, pushing him aside.

“It’s disgusting!” Bard exclaimed in delight.

“It’s old as old, that’s for sure,” said Vigot, swinging the creature in front of the children. “Stuck in the mud for years and years, just waiting for you.”

“Throw it back,” Brita told him.

“What? So it can rise again when the world ends?”

Vigot lowered the sea creature onto the deck, and then he and Slothi and the children poked it and prodded it.

Solveig, meanwhile, was distracted by Bergdis and Edith.

“Three,” Bergdis announced, slapping her stomach. “Three I’ve lost. And I’m very healthy and wide-hipped. Two of them were boys.”

“If I have a son . . .” Edith began, but Bergdis interrupted her. “Then I lost my man Jorund. I lost him to Ran.”

“Another woman?”

Bergdis snorted. “Of a kind. Ran with her drowning net.”

“Oh! You mean the goddess,” Edith said.

“Now, Jorund—he was a real man,” Bergdis told her. And then more loudly: “Is there anyone aboard this boat red-blooded?”

“Enough, Bergdis!” Red Ottar snapped.

“Red-blooded!” said Bergdis very deliberately. “You, Bruni?”

“I’m warning you,” Red Ottar told her.

“Well, there is one,” Bergdis confided to Edith in a sly voice, and Solveig found herself leaning forward.

“He knows who he is,” Bergdis said. “But men . . . they’re seldom satisfied for long.”

Solveig heard someone running up the gangplank.

A little man hopped off the end of it, took a big step, and with a jump landed right beside Solveig.

“Mihran!” he announced.

Solveig couldn’t help smiling at the very sight of him. He was as little and lightly built as Oleg but much darker-skinned, and his eyes were twinkling, as if to say the best thing to do about life was to laugh at it.

“Everyones know Mihran,” the man told Solveig. “Everyones in Ladoga and Kiev.”

Red Ottar stood up to greet the third pilot. “Everyone may know you,” he said. “But what about you? Do you know the rivers, the rapids, the lakes?”

Torsten walked up to the skipper’s side, still holding the knotted rope, and Mihran immediately pointed at it. “Turk’s head!” he said, clasping his hands around his neck and laughing. “Me Armenian. We hate Turkeys!”